1. Introduction

The persistent lack of diversity within geoscience faculty ranks is a well-documented issue. Despite ongoing efforts to enhance representation, particularly concerning race, ethnicity, and gender, significant disparities remain. While initiatives focusing on inclusive hiring practices, mentorship programs, and family-friendly policies are crucial, a less explored yet equally impactful factor influencing faculty recruitment is geographic preference. This article delves into the pivotal role of geographic considerations in the job search decisions of geoscientists from underrepresented groups, drawing insights from interviews with 19 geoscientists who recently declined tenure-track faculty job offers.

Geoscience departments are increasingly recognizing the imperative of diversifying their faculty. This drive stems not only from principles of equity and social justice within academia but also from the acknowledged benefits that diversity brings to scientific innovation and societal impact. Diverse teams are proven to enhance problem-solving, foster broader perspectives, and improve decision-making – qualities essential for addressing the complex and globally relevant challenges within geosciences. Moreover, a diverse faculty body can serve as crucial role models, mitigating stereotype threat and implicit biases while enriching the learning environment for students, especially those from underrepresented backgrounds.

Despite these compelling motivations and various departmental initiatives, geoscientists from underrepresented groups continue to face significant hurdles in academic career advancement. Experiences of discrimination, harassment, and mistreatment are disproportionately reported by geoscientists of color, women, and nonbinary individuals, leading to higher rates of attrition and career dissatisfaction. Therefore, understanding and addressing the multifaceted barriers in faculty hiring is paramount to achieving meaningful and sustainable diversification within geosciences.

Prior research has explored various interventions to diversify faculty, including supporting dual-career couples, implementing family-friendly policies, enhancing mentorship, and modifying hiring practices. However, a critical gap exists in understanding how geoscientists from underrepresented groups perceive these interventions and, more broadly, their narratives surrounding job search experiences. This article addresses this gap by examining the faculty job search experiences of 19 geoscientists from underrepresented groups who declined tenure-track offers. Through in-depth interviews, we identify key factors influencing their decisions, with a particular focus on geographic preferences and their interplay with other critical elements such as departmental commitment to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), interview experiences, negotiation processes, and compatibility with personal life. By illuminating these factors, we aim to provide actionable recommendations for geoscience departments to refine their recruitment strategies, fostering more equitable and effective hiring practices that attract and retain a diverse faculty.

2. Findings

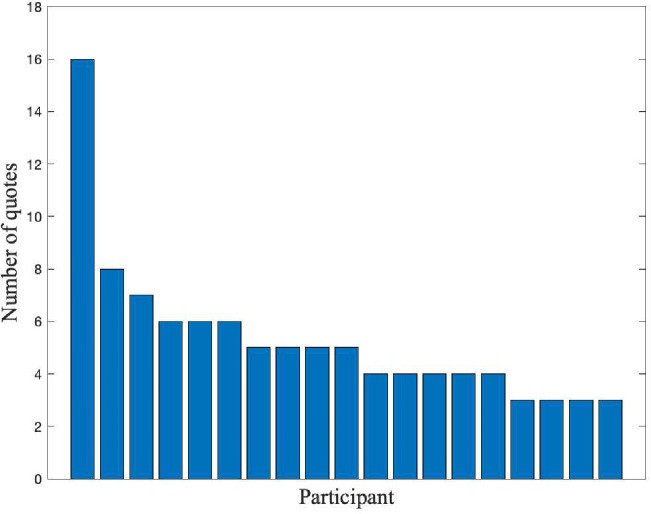

The subsequent sections present findings derived from interviews with 19 geoscientists who declined tenure-track faculty job offers. These findings are structured around key themes that emerged from the interview data, highlighting the significant role of geographic preferences in conjunction with departmental DEI commitment, interview civility, negotiation values, and personal life compatibility. Exemplary quotes from participants are incorporated to illustrate the nuances and personal dimensions of these experiences.

2.1. Departmental Commitment to Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

A strong and genuine commitment to DEI emerged as a critical factor influencing candidates’ decisions. Participants actively assessed a department’s DEI commitment throughout the hiring process, considering it a vital element in their evaluation of job offers. This assessment encompassed various aspects, including explicit support for DEI initiatives, the integration of DEI discussions during interviews, respect for candidates’ personal identities, departmental demographics, the experiences of underrepresented faculty members, mentorship structures for junior faculty, and the perceived value placed on student mentorship.

2.1.1. Personal Identities

Personal identities were inextricably linked to participants’ job searches. Many candidates sought departments, universities, and communities where their identities would be represented and respected. Geographic preferences were often shaped by these identity considerations, with participants prioritizing locations where they felt a sense of belonging and safety. Experiences during interviews and negotiations were also viewed through the lens of personal identities, with some participants encountering situations that reflected biases or a lack of understanding.

Tokenism emerged as a concern for several participants. They perceived instances where departments seemed more focused on diversity statistics than genuine inclusion, making them feel valued primarily for their identity rather than their scholarly contributions. Conversely, the presence of role models who shared similar identities and perspectives was highly valued.

2.1.2. DEI Initiatives

Participants’ experiences with DEI initiatives during the hiring process varied significantly. While some encountered departments genuinely invested in DEI, others perceived DEI efforts as superficial or performative. A department’s approach to DEI, or lack thereof, directly influenced candidates’ perceptions and decisions. Notably, some participants observed that DEI discussions were often relegated to students and junior faculty, raising concerns about the depth of commitment from senior faculty. Conversely, departments that openly addressed DEI, used inclusive language, and demonstrated a genuine interest in fostering an equitable environment were viewed favorably.

2.1.3. Mentorship

Mentorship emerged as a crucial support system for geoscientists from underrepresented groups navigating academic career paths. Participants highlighted the importance of mentorship from PhD and postdoctoral advisors, peers, and within teaching contexts. For some, the availability of strong mentorship opportunities outweighed even compensation considerations. Conversely, a perceived lack of mentorship, or experiences where mentorship was withheld or undermined due to personal biases, negatively impacted job offer evaluations. The appeal of positions that included mentorship responsibilities was also evident, reflecting a desire to both receive and provide mentorship within their academic roles.

2.2. (In)civility during Job Interviews

Job interviews served as critical windows into departmental culture, with experiences ranging from highly positive to deeply negative. Positive experiences included departments demonstrating consideration for candidates’ needs, fostering positive interactions with faculty, exhibiting camaraderie, and facilitating meaningful engagement with students. These positive interactions significantly enhanced candidates’ perceptions of job opportunities.

However, a concerning number of participants reported negative interview experiences that significantly deterred them. These included unsettling encounters related to faculty with known histories of misconduct, illegal or inappropriate questions, disparaging comments, and a general lack of engagement or interest from faculty interviewers. The perceived civility, or lack thereof, during interviews often reflected broader departmental culture issues and significantly influenced candidates’ decisions to accept or decline offers. Notably, some negative experiences were directly linked to participants’ personal identities, underscoring the intersectional nature of biases in hiring processes.

2.3. Values Revealed in Negotiation

Negotiation processes extended beyond salary and startup packages, serving as crucial indicators of institutional support and values. Confusing negotiation tactics, such as asking candidates to define their needs before presenting an initial offer, created uncertainty and unease. Family considerations, particularly partner hires, frequently arose during negotiations, with successful partner accommodations significantly enhancing job appeal. Conversely, dismissive or unsupportive responses to partner hire requests or family needs were major deterrents.

Lowball salary offers, offers below postdoctoral salaries, or inflexible negotiation stances signaled a lack of value and respect, leading many candidates to decline offers. The negotiation process, therefore, served as a critical litmus test for candidates, revealing underlying institutional values and influencing their decisions beyond the immediate terms of the offer. Transparency, respect, and a willingness to engage in good-faith negotiation were highly valued, while perceived inflexibility or disrespect significantly undermined job appeal.

2.4. Compatibility with Personal Life

Personal life considerations were universally important for all participants, regardless of relationship or parental status. Family, broadly defined, played a central role in job search decisions. Geographic preferences were deeply intertwined with personal life, often driven by proximity to family, partner employment opportunities, and desired community characteristics.

2.4.1. Partner and Family

Partners’ preferences and needs were integral to job search decisions. Many participants prioritized locations that accommodated their partners’ careers and geographic preferences. Partner hires were frequently negotiated and significantly influenced offer acceptance. Despite the importance of family considerations, some participants felt compelled to conceal their family status during interviews, fearing potential biases. Conversely, departments that openly acknowledged and supported work-life balance, including family needs, were viewed positively. The desire to be closer to relatives and establish supportive personal networks also shaped geographic preferences.

2.4.2. Geographic Preferences

Geographic preferences emerged as a powerful and often decisive factor in participants’ job search decisions. While many acknowledged the limited luxury of being geographically selective in a competitive academic job market, strong preferences based on a variety of factors were evident. These factors extended beyond mere location aesthetics, encompassing critical considerations such as state and local politics, community safety, race relations, diversity, and urban versus rural environments.

Political climate emerged as a significant geographic consideration. Participants expressed wariness towards states with increasingly conservative politics, citing concerns about academic freedom, reproductive rights, gender-affirming care access, and broader social values. These political concerns were not merely abstract; they directly impacted participants’ perceptions of personal safety, professional autonomy, and overall quality of life in different geographic locations. The perceived political landscape of a state or region could be a dealbreaker, even for prestigious job offers.

Community diversity was another key geographic preference. Many participants sought locations with diverse populations and inclusive communities where they felt they and their families would belong and thrive. This desire for community diversity was often linked to personal identities, with participants prioritizing locations where they felt safe and represented. Urban environments, with their inherent diversity and broader range of social and cultural amenities, were often favored over more remote or homogenous locations.

2.5. Other Considerations

Beyond the primary themes, other factors influenced participants’ decisions. Some participants expressed negative perceptions of broad job advertisements, viewing them as impersonal or indicative of less targeted recruitment efforts. The timing of reference letter requests also mattered, with upfront requests perceived as burdensome. Departmental reputation, both positive and negative, significantly influenced application decisions. Overall, the job search was described as a deeply personal process, with safety concerns on college campuses and imposter syndrome also surfacing as relevant factors. The perceived pressure to accept tenure-track offers, even when misaligned with personal or professional priorities, added another layer of complexity to decision-making.

3. Discussion

The collective experiences of the 19 participants underscore several critical areas for improvement in geoscience faculty hiring practices. While some existing recommendations align with participants’ preferences, others warrant further attention and refinement. Given the urgency of diversifying geoscience faculty, particularly with underrepresented groups, the following recommendations are synthesized from our findings to guide departmental hiring practices towards greater equity and effectiveness.

3.1. Recommendations for Equitable and Effective Faculty Hiring

The recommendations below are categorized for clarity and summarized in Table 1. They aim to provide actionable steps for geoscience departments to enhance their hiring processes, making them more attractive to diverse candidates and ultimately fostering a more inclusive and equitable academic environment.

Respect Personal Identities:

- Avoid Tokenism: Departments should ensure candidates feel valued for their scholarly contributions and potential, not solely for their identity or perceived contribution to diversity statistics. Highlighting candidates’ strengths and research impact beyond diversity contributions is crucial.

- Be Aware of Invisible Identities: Recognize and respect the multifaceted nature of identity, including aspects that may not be immediately visible. Create an inclusive environment where diverse identities are acknowledged and valued.

- Use Correct Pronouns: Demonstrate respect and inclusivity by using candidates’ correct pronouns. This seemingly small act significantly contributes to a welcoming and respectful atmosphere.

- Support International Faculty: Provide proactive and comprehensive support for international faculty in navigating visa processes. Addressing visa concerns can significantly enhance job offer appeal for international candidates.

Support Departmental DEI Efforts:

- Diversify at All Levels: Strive for diversity across all faculty ranks, staff, and student bodies. Visible diversity at all levels signals a genuine and sustained commitment to inclusion.

- Be Well-Informed on DEI Issues: Ensure hiring committees and faculty members are well-versed in DEI best practices and current issues. Demonstrate a sophisticated understanding of DEI beyond superficial gestures.

- Encourage Senior Faculty Engagement in DEI: Promote active participation of senior faculty in DEI initiatives. Visible commitment from senior faculty signals institutional prioritization of DEI and can inspire broader departmental engagement.

Improve and Communicate Mentorship Programs:

- Mentor Junior Faculty: Establish robust mentorship programs for junior faculty, encompassing research, teaching, and career development. Highlighting mentorship opportunities can be a significant draw for early-career academics.

- Encourage and Support Faculty Mentorship of Students and Postdocs: Recognize and reward faculty contributions to student and postdoc mentorship. A culture of mentorship enhances the overall academic environment and supports the development of future generations of geoscientists.

- Offer Teaching Mentorship: Provide mentorship specifically focused on teaching for new faculty. Teaching mentorship can alleviate anxieties and enhance the onboarding experience for new hires.

Improve Underlying Departmental Issues:

- Enhance Student and Faculty Satisfaction: Address underlying issues contributing to student and faculty dissatisfaction. A positive and supportive departmental culture is a powerful recruitment tool.

- Promote Work-Life Balance: Actively cultivate and support work-life balance for faculty. Highlighting work-life balance initiatives can be particularly attractive to candidates seeking a sustainable academic career.

- Improve Departmental Cohesion: Foster a cohesive and collegial departmental environment. A sense of community and collaboration enhances job satisfaction and recruitment appeal.

- Reduce Unprofessional Behavior and Eliminate Misconduct: Actively address and eliminate unprofessional behavior and misconduct. A safe and respectful environment is paramount for attracting and retaining diverse faculty.

Increase Departmental Awareness of Hiring Best Practices:

- Avoid Illegal Questions: Educate hiring committees on legal and illegal interview questions. Strict adherence to legal guidelines is essential for ethical and equitable hiring.

- Eliminate Disparaging Behavior: Prohibit disparaging comments or behaviors towards candidates. Maintain a respectful and professional tone throughout the hiring process.

- Offer Accommodations via a Neutral Party: Provide accommodations through a neutral third party to protect candidate privacy and avoid potential biases. Streamlining accommodation requests ensures equitable access for all candidates.

- Maintain Professionalism During Interviews: Uphold a high standard of professionalism throughout all interview interactions, formal and informal. Professionalism signals respect and organizational competence.

- Engage Fully with Candidates: Demonstrate genuine interest in candidates’ research and potential contributions. Active engagement signals that candidates are valued and their work is appreciated.

- Avoid Alcohol: Refrain from serving alcohol during interview events. Alcohol can create uncomfortable situations and potentially disadvantage candidates from underrepresented groups.

Negotiate in Good Faith:

- Ensure Transparent Negotiation: Establish a transparent and clear negotiation process. Transparency builds trust and facilitates smoother negotiations.

- Work with Candidate Timelines and Preferences: Be flexible and accommodating to candidate timelines and individual preferences during negotiation. Flexibility demonstrates respect and a willingness to work collaboratively.

- Accommodate Partner Needs: Actively seek and facilitate employment opportunities for partners. Partner accommodation is a crucial factor for many dual-career academic couples.

- Maintain Politeness and Respect: Uphold politeness and respect throughout the negotiation process, regardless of negotiation outcomes. Respectful communication maintains positive relationships and departmental reputation.

- Offer Competitive Compensation: Provide competitive salary and startup packages commensurate with experience and field standards. Competitive offers signal institutional investment in faculty success.

- Provide Sufficient Decision Time: Grant candidates adequate time to consider offers. Avoid rushed deadlines that pressure candidates and limit thoughtful decision-making.

Improve and Communicate Support for Partners and Children:

- Facilitate Partner Employment: Actively assist partners in finding meaningful employment opportunities within the university or local area. Proactive partner support significantly enhances job offer appeal.

- Enhance and Communicate Support for Parents: Improve and clearly communicate support systems for faculty parents, including childcare resources, parental leave policies, and flexible work options. Family-friendly policies are increasingly important for attracting and retaining faculty.

- Improve and Communicate Work-Life Balance Support: Showcase institutional commitment to work-life balance through policies, programs, and cultural norms. Highlighting work-life balance initiatives can be a significant recruitment advantage.

Make the Hiring Process Candidate-Friendly:

- Request Letters for Finalists Only: Request recommendation letters only for shortlisted candidates. Reducing the burden of letter requests respects recommenders’ time and streamlines the application process.

- Avoid Broad Searches: Employ targeted recruitment strategies rather than relying solely on broad, generic job advertisements. Focused searches demonstrate a clear understanding of departmental needs and candidate profiles.

Table 1: Summary of recommendations for geoscience departments to enhance faculty hiring practices and promote diversity, equity, and inclusion.

3.2. Geographic Preferences: A Key Factor in DEI

Geographic preferences are not merely personal whims; they are deeply intertwined with personal identities, family considerations, and broader societal factors, particularly for underrepresented groups. Ignoring geographic preferences in faculty recruitment is detrimental to DEI efforts. Departments located in areas perceived as politically unwelcoming, lacking in diversity, or posing safety concerns will face significant challenges in attracting diverse faculty, regardless of other institutional strengths.

Universities and departments must proactively address geographic concerns to enhance their appeal to diverse candidates. This includes:

- Acknowledging and Addressing Political Concerns: Openly acknowledge and address concerns about state and local political climates. Highlighting university initiatives that promote inclusivity and protect academic freedom can mitigate political anxieties.

- Showcasing Community and University Diversity: Actively promote the diversity of the university and surrounding community. Demonstrate a commitment to creating inclusive environments both within and beyond campus boundaries.

- Offering Flexibility and Relocation Support: Explore flexible work arrangements and provide robust relocation support packages. Addressing logistical and financial barriers associated with relocation can widen the candidate pool.

- Improving Departmental Culture to Enhance Location Appeal: Cultivating a positive, supportive, and inclusive departmental culture can enhance the overall appeal of a location, even if the geographic setting presents some challenges. A strong departmental community can be a powerful draw.

3.3. Future Research Directions

This study highlights the need for further research in several areas. Longitudinal studies tracking the career trajectories of faculty hired with attention to geographic preferences would be valuable. Investigating the specific mechanisms through which universities can effectively address political and social concerns related to geographic location is also warranted. Further exploration of the intersectionality of geographic preferences with other aspects of identity, such as socioeconomic background and disability status, is crucial for a more comprehensive understanding of DEI in faculty hiring.

4. Methods

4.1. Participant Recruitment

Participants were recruited through targeted outreach to affinity groups, institutional email lists, and social media platforms relevant to geoscientists from underrepresented groups. Eligibility criteria included self-identification as a geoscientist from an underrepresented race, ethnicity, and/or gender who had declined at least one tenure-track faculty job offer at a US institution between 2016 and 2023. A screening survey was used to identify eligible participants and ensure representation across demographic categories. Convenience sampling was employed due to the lack of a comprehensive sampling frame for this specific population. Ethical guidelines were followed, and informed consent was obtained from all participants, with the study approved by the NSF NCAR’s Human Subjects Committee (HSC).

4.2. Interview Methods

Semi-structured interviews, lasting approximately 45 minutes, were conducted with each of the 19 participants. A standardized interview protocol (Appendix B in the original article) guided the conversations, allowing for flexibility to explore emergent themes and individual experiences in depth. Interviews focused on participants’ job search logistics, decision-making factors, interview and negotiation experiences, DEI considerations, personal identity influences, and family/partner impacts. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analyzed to identify recurring themes and patterns. Thematic analysis was used to categorize and synthesize participant responses, focusing on the interplay of geographic preferences with other key factors.

4.3. Limitations

This study is limited to the experiences of geoscientists in the US, primarily focusing on tenure-track faculty positions within the 2016-2023 timeframe. The COVID-19 pandemic and concurrent social movements may have influenced hiring practices during this period. The focus on gender and race/ethnicity as underrepresented categories, while significant, does not encompass all aspects of identity relevant to DEI. The overrepresentation of cisgendered women in the sample, compared to underrepresented racial/ethnic groups, is a limitation, as the barriers faced by these groups can differ. The exclusion of cisgendered white men, while intentional to focus on underrepresented perspectives, also limits the scope of the study. Voluntary participation and potential interviewer bias are additional limitations to consider.

Acknowledgements

We extend our sincere gratitude to the 19 geoscientists who generously shared their experiences, making this study possible. We also thank all geoscientists who completed the recruitment survey. Publication support was provided by NSF NCAR Education, Engagement, and Early Career Development (EdEC). We acknowledge Scott Landolt (NSF NCAR) and Rohini Shivamoggi for their valuable feedback and discussions. This work was supported by the NSF National Center for Atmospheric Research and NOAA MAPP under award NA20OAR4310392. Lyssa Freese’s work was supported by Gates Ventures LLC and NIEHS Toxicology Training Grant no. T32-ES007020.

Appendix A. Survey questions

(Appendix A content from the original article)

Appendix B. Interview questions

(Appendix B content from the original article)

Footnotes

(Footnotes content from the original article)

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article due to participant confidentiality.

References

(References content from the original article)

Associated Data

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article due to the confidential nature of the data.