The landscape of health insurance in the United States underwent significant transformation with the introduction of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in 2010. A cornerstone of this act, effective from January 1, 2014, was the mandate preventing insurance providers from denying coverage or imposing higher premiums based on pre-existing health conditions. This pivotal change, often referred to as guaranteed issue and modified community rating, aimed to broaden access to health insurance, particularly for individuals with chronic illnesses who previously faced significant barriers to obtaining coverage.

Coupled with tax subsidies designed to assist low and middle-income individuals in purchasing insurance through newly established health insurance marketplaces, these provisions of the Affordable Care Act sought to make healthcare more accessible and affordable. However, policymakers recognized that these reforms, while beneficial, could potentially destabilize the insurance market if not carefully managed. The core concern was the risk of insurers competing to attract healthier, lower-cost enrollees while avoiding those with greater healthcare needs – a practice known as risk selection. Furthermore, the initial years of market reform brought considerable uncertainty for insurers attempting to accurately price their plans in the face of a newly expanded pool of insured individuals, including those previously deemed “uninsurable.” This uncertainty had the potential to lead to significant fluctuations in premiums, undermining the stability of the market.

To address these challenges and foster a more stable and competitive health insurance market, the ACA incorporated three key programs: risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors. These programs were specifically designed to incentivize insurers to compete based on the quality and value of their plans, rather than by seeking to enroll only the healthiest individuals. This article will delve into these three crucial mechanisms, with a particular focus on the Affordable Care Act Aca Risk Adjustment Program, explaining their functions, objectives, and impacts on the health insurance market, especially during the critical early years of the ACA’s implementation.

The Challenges of Adverse Selection and Risk Selection

To fully appreciate the role and importance of the ACA’s risk adjustment program, it’s essential to understand the concepts of adverse selection and risk selection in the context of health insurance markets.

Adverse selection arises from the information asymmetry between insurers and consumers. Individuals who anticipate needing more healthcare services are more likely to seek insurance coverage than those who expect to remain healthy. In a market with guaranteed issue, where insurers cannot deny coverage based on pre-existing conditions, this can lead to a disproportionate enrollment of sicker individuals. This, in turn, can drive up average healthcare costs and consequently, premiums for everyone in the insurance pool. If premiums become too high, healthier individuals may choose to forgo insurance, further skewing the risk pool towards sicker individuals and creating a detrimental cycle of rising premiums and market instability. The ACA attempts to mitigate adverse selection through several mechanisms, including mandating most individuals to have health insurance or face a penalty (the individual mandate, though later repealed), establishing open enrollment periods to prevent people from waiting until they are sick to purchase insurance, and providing subsidies to make insurance more affordable for eligible individuals.

Risk selection, on the other hand, refers to the strategies insurers might employ to avoid enrolling individuals who are likely to incur high healthcare costs. Even though the ACA prohibits insurers from explicitly denying coverage or charging higher premiums based on health status, insurers might still attempt to attract healthier enrollees and discourage sicker ones. This could be achieved through plan design choices, such as offering plans with less comprehensive benefits, higher deductibles, or restrictive drug formularies that are less appealing to individuals with chronic conditions or significant healthcare needs. Alternatively, plans with lower premiums and higher cost-sharing might inherently attract a healthier demographic who are less concerned about immediate healthcare needs. Such risk selection behaviors undermine the efficiency of the market, as insurers may prioritize attracting healthier individuals over competing on the basis of providing better value and quality of care to all consumers.

The ACA’s risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors programs were specifically designed to counteract the potential negative impacts of both adverse selection and risk selection, aiming to stabilize premiums and ensure a more equitable and functional health insurance market, particularly during the initial phase of the ACA’s implementation.

The following table summarizes the key features of these three programs:

| Table 1: Summary of Risk and Market Stabilization Programs in the Affordable Care Act |

|---|

| Risk Adjustment |

| What the program does |

| Whyit was enacted |

| Who participates |

| How it works |

| Whenit goes into effect |

Deep Dive into the Risk Adjustment Program

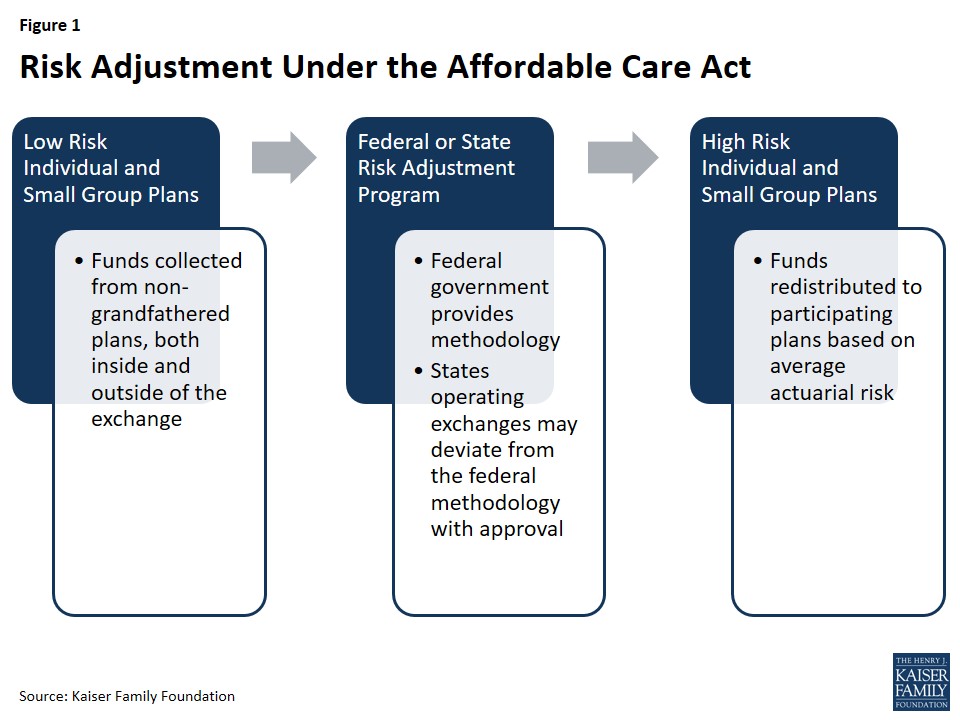

The Affordable Care Act ACA risk adjustment program stands as a permanent fixture, designed to reinforce the ACA’s market regulations that prohibit risk selection by insurance companies. Its primary mechanism is to transfer funds from health insurance plans with a predominantly healthy, lower-risk enrollee population to plans that cover a higher proportion of individuals with significant health needs and higher expected healthcare costs.

The overarching goal of the risk adjustment program is to foster a health insurance market where insurers are incentivized to compete on the basis of plan quality, efficiency of care delivery, and overall value for consumers. Instead of focusing on attracting only the healthiest individuals, insurers are encouraged to develop comprehensive and cost-effective plans that cater to a diverse population with varying health statuses.

Furthermore, the risk adjustment program plays a crucial role in stabilizing premiums, both within and outside of the health insurance marketplaces. By mitigating the financial incentives for insurers to engage in risk selection (for example, by offering less attractive plans outside the exchanges to steer sicker individuals towards exchange coverage), the program contributes to a more level playing field. This stability also extends to the federal government’s financial obligations related to tax credit subsidies, as it helps to control costs associated with these subsidies by preventing excessive premium increases driven by risk selection behaviors.

Program Participation: Who is Involved?

The risk adjustment program has broad applicability, encompassing non-grandfathered health insurance plans in both the individual and small group markets. This includes plans offered both within and outside of the health insurance exchanges (marketplaces). However, certain types of plans are exempt from participation.

Plans that were already in existence when the ACA was enacted in March 2010 are considered “grandfathered” and are subject to fewer of the ACA’s requirements, and thus are part of the risk adjustment system. However, plans can lose their grandfathered status if they undergo significant changes, such as substantial increases in cost-sharing or the imposition of new annual benefit limits. Additionally, plans renewed before January 1, 2014, which are not yet fully subject to the ACA’s mandates, are also not included in the risk adjustment system. Multi-state plans and Consumer Operated and Oriented Plans (COOPs), which were created under the ACA to foster competition, are subject to risk adjustment.

Unless a state opts to merge its individual and small group markets, separate risk adjustment systems operate in each market. This ensures that risk is adjusted appropriately within each distinct market segment.

Government Oversight: Federal and State Roles

The administration and oversight of the risk adjustment program involve both federal and state governments, with the degree of state involvement varying depending on whether the state operates its own health insurance exchange.

States that operate their own state-based exchanges have the option to establish and run their own risk adjustment programs. Alternatively, they can choose to have the federal government (specifically, the Department of Health and Human Services, or HHS) administer the program on their behalf. However, states that do not operate their own exchange and instead utilize the federally-run exchange (Health Insurance Marketplace) do not have the option to run their own risk adjustment programs and must rely on the federal model. In states where HHS operates the risk adjustment program, insurance issuers are charged a fee to cover the administrative costs of the program.

HHS has developed a federally-certified risk adjustment methodology that is used by states that opt for the federal program, and serves as a benchmark for state-run programs. States wishing to implement an alternative risk adjustment model must seek federal approval from HHS and are required to submit annual reports detailing their program operations. States choosing to run their own programs are also required to publish a notice of benefit and payment parameters by March 1st of the year preceding the benefit year; failure to do so means they must adhere to the federal methodology. Once a state’s alternative methodology is federally certified, it can potentially be adopted by other states as well. Interestingly, Massachusetts was the only state to initially operate its own risk adjustment program but discontinued it in 2017. As of 2017, HHS operates the risk adjustment program in all states.

Calculation of Payments and Charges: How Risk is Assessed

At the heart of the risk adjustment program is a sophisticated methodology for assessing and comparing the average financial risk of enrollees in different health insurance plans. The HHS methodology utilizes enrollee demographics and claims data for specified medical diagnoses to estimate financial risk. It then compares plans within the same geographic area and market segment based on the average risk of their enrollees to determine which plans will be required to make payments into the system and which will receive payments.

The cornerstone of this calculation is the individual risk score. This score is assigned to each enrollee based on factors such as age, sex, and medical diagnoses. Diagnoses are categorized using a Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) system, with each category assigned a numeric value reflecting the relative healthcare expenditures expected for an enrollee with that type of medical diagnosis. If an enrollee has multiple, unrelated diagnoses, the HCC values for each are incorporated into the individual risk score. Furthermore, for adult enrollees with certain combinations of illnesses (such as a severe illness and an opportunistic infection), an interaction factor is added to their individual risk score to account for the increased complexity and cost of care. Finally, if an enrollee is receiving subsidies to reduce their cost-sharing under the ACA, an induced utilization factor is applied to account for the potential increase in demand for healthcare services due to lower out-of-pocket costs.

Once individual risk scores are calculated for all enrollees in a plan, these scores are averaged to arrive at the plan’s average risk score. This average risk score serves as a measure of the plan’s predicted expenses. The HHS methodology also incorporates adjustments for various factors, including the actuarial value of the plan (reflecting the extent of patient cost-sharing), allowable rating variation, and geographic cost variations to ensure a fair comparison across different plan designs and locations.

Under the risk adjustment mechanism, plans with a relatively low average risk score, indicating a healthier enrollee population, are required to make payments into the system. Conversely, plans with a relatively high average risk score, indicating a sicker enrollee population, receive payments. These transfers (both payments and charges) are calculated by comparing each plan’s average risk score to a baseline premium, which is the average premium in the state. Calculations are performed for each geographic rating area, meaning that insurers operating in multiple rating areas within a state will have multiple transfer amounts, which are then consolidated into a single invoice. Crucially, the total payments and charges within a given state’s risk adjustment system are designed to net to zero, ensuring that the program is budget-neutral.

In March 2016, CMS (Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) convened a public conference and released a white paper to review the risk adjustment methodology and incorporate lessons learned from the initial years of implementation. The white paper explored proposals to account for partial-year enrollees and prescription drug utilization within the risk adjustment model. Subsequently, CMS proposed to incorporate partial-year enrollment into the model for the 2017 benefit year and prescription drug utilization for the 2018 benefit year. Starting in 2017, preventive services were also integrated into the simulation of plan liability, and different trend factors were introduced for traditional drugs, specialty drugs, and medical/surgical expenditures to better reflect the rising costs of prescription drugs relative to other medical expenses. The risk adjustment model was recalibrated using the most recent claims data from the Truven Health Analytics MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters database. Responding to feedback from insurers during the 2014 benefit year, CMS also began providing insurers with early estimates of plan-specific risk adjustment calculations to provide more timely information for premium setting. Furthermore, CMS has indicated ongoing exploration of options to refine the permanent risk adjustment program to better account for higher-cost enrollees, particularly as the temporary reinsurance program phased out in 2016.

Data Collection and Privacy: Protecting Enrollee Information

To operate effectively, the federal risk adjustment program requires the collection of substantial data. However, it also incorporates robust measures to protect consumer privacy and confidentiality. Insurers are responsible for providing HHS with de-identified data, including enrollees’ individual risk scores. States that run their own programs are not mandated to use this specific data collection model but are required to collect only the information reasonably necessary for program operation and are prohibited from collecting personally identifiable information. Insurers are permitted to require healthcare providers and suppliers to submit the necessary data for risk adjustment calculations.

For each benefit year, issuers of risk adjustment-covered plans (and reinsurance-eligible plans) must establish a dedicated data environment, known as an EDGE server (External Data Gathering Environment), and provide HHS with data access within a specified timeframe to be eligible for risk adjustment and/or reinsurance payments. CMS has issued detailed guidance on EDGE data submissions for benefit years.

To ensure the accuracy of reported data, HHS recommends that insurers conduct an independent audit of their data before submitting it to HHS for a second audit. For the initial benefit years (2014 and 2015), no adjustments to payments or charges were made as HHS focused on optimizing the data validation process. However, starting in 2016, if an issuer fails to establish an EDGE server, fails to submit risk adjustment data, or if errors are detected during audits, the insurer’s average actuarial risk, payments, and charges are subject to adjustment. Due to the multi-year nature of the audit process, the first adjustments to payments (for the 2016 benefit year) were issued in 2018. Issuers that fail to provide timely access to EDGE server data face a default risk adjustment charge. In 2015, the vast majority of participating issuers successfully submitted EDGE server data, with only a small number assessed the default charge.

Payments for the 2014 and 2015 Benefit Years: Initial Program Outcomes

The results of the risk adjustment program for the first benefit year, 2014, were announced by HHS on October 1, 2015. For 2014, a total of $4.6 billion was transferred among insurers through the risk adjustment program, with 758 issuers participating. Independent analyses indicated that the relative health of enrollees was the primary factor determining whether an issuer received a risk adjustment payment, suggesting that the risk adjustment formula was functioning as intended – transferring funds from plans with healthier enrollees to those with sicker enrollees. CMS reported this outcome as a positive sign that the program was effectively promoting access, quality, and choice for consumers.

On June 30, 2016, HHS released a summary report detailing the results for the 2015 benefit year. Risk adjustment transfers in 2015 averaged around 10% of premiums in the individual market and 6% in the small group market, consistent with the 2014 experience. A total of 821 issuers participated in the risk adjustment program in 2015. HHS also provided each participating issuer with a report outlining their specific risk adjustment payment or charge.

It’s important to note that risk adjustment payments to issuers for the 2015 benefit year were subject to sequestration at a rate of 7% due to government-wide sequestration requirements for fiscal year 2016. However, HHS indicated that these sequestered funds were expected to become available for payment to issuers in fiscal year 2017 without further Congressional action.

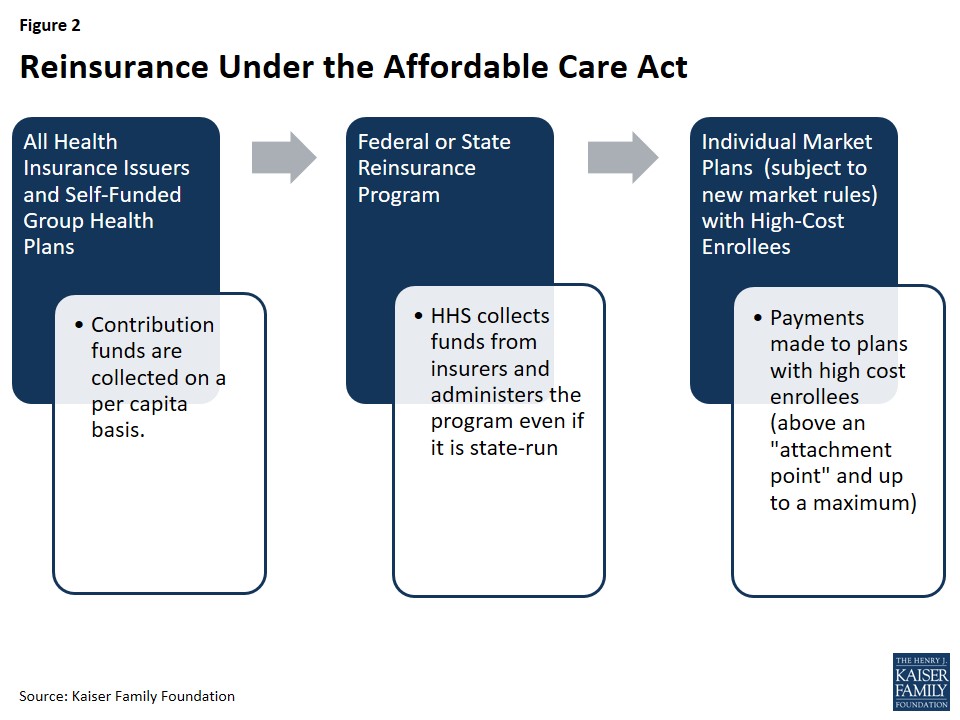

Reinsurance: A Temporary Premium Stabilizer

The ACA also included a temporary reinsurance program, active from 2014 through 2016. Its primary purpose was to stabilize premiums in the individual market during the initial years of market reforms, particularly the implementation of guaranteed issue. The program aimed to reduce the incentive for insurers to set higher premiums due to concerns about enrolling a disproportionate number of higher-risk individuals in the early years of the reformed market.

Reinsurance operates differently from risk adjustment. While risk adjustment is designed to mitigate risk selection across plans, reinsurance focuses on reducing the overall risk pool in the individual market by providing financial support for plans that enroll high-cost individuals. Reinsurance payments are exclusively directed to individual market plans that are subject to the ACA’s new market rules, whereas risk adjustment applies to both individual and small group plans. Furthermore, reinsurance payments are based on actual healthcare costs incurred, while risk adjustment payments are based on predicted costs. This means reinsurance also accounts for unexpectedly high costs in low-risk individuals, such as those resulting from accidents or sudden illnesses. Notably, plans could potentially receive both reinsurance and risk adjustment payments for the same high-cost/high-risk enrollees.

Unlike risk adjustment, which is budget-neutral within each market segment, reinsurance represents a net inflow of funds into the individual market, effectively subsidizing premiums in that market for its temporary duration. To fund reinsurance payments and program administration, contributions are collected from all health insurance issuers and third-party administrators across all market segments (individual, small group, and large group). HHS distributes reinsurance payments based on need, rather than proportionally to state contributions, ensuring funds are directed where they are most needed to stabilize the individual market.

Program Participation: Who Contributes and Who Benefits?

A broad range of entities contribute to the reinsurance program. This includes all issuers of fully-insured major medical products in the individual, small group, and large group markets, as well as self-funded plans. However, reinsurance payments are specifically targeted to benefit individual market issuers that cover high-cost individuals and are subject to the ACA’s market rules. State high-risk pools, which existed prior to the ACA to cover individuals with pre-existing conditions, are excluded from the reinsurance program.

Government Oversight: Primarily Federal with Limited State Options

The reinsurance program is primarily federally overseen. While states had the option to operate their own reinsurance programs, the flexibility to deviate from federal guidelines was limited. HHS collected all reinsurance contributions, even for state-run programs, and all states were required to adhere to a national payment schedule. States wishing to modify data requirements were required to publish a notice of benefit and payment parameters. States could choose to collect additional funds if they anticipated that reinsurance payments and program administration costs would exceed the nationally specified amount. Although states could continue reinsurance programs beyond 2016, they were prohibited from using funds collected under the ACA’s reinsurance program after 2018. Connecticut was the only state to operate its own reinsurance program for the 2014 and 2015 benefit years. In July 2016, Alaska enacted a two-year reinsurance program that effectively repurposed the state’s high-risk pool as a reinsurance fund, covering claims for the 2015 and 2016 benefit years.

Calculation of Payments and Charges: Attachment Points, Caps, and Coinsurance

The ACA established national funding levels for reinsurance, set at $10 billion in 2014, $6 billion in 2015, and $4 billion in 2016. Based on enrollment estimates, HHS set a uniform reinsurance contribution rate per person: $63 in 2014, $44 in 2015, and $27 in 2016.

Reinsurance payments were triggered when an eligible insurance plan’s costs for an enrollee exceeded a certain threshold, known as the attachment point. HHS set the attachment point at $45,000 for 2014 and 2015. Due to the reduced reinsurance funding pool in 2016, the attachment point was raised to $90,000 for that year. A reinsurance cap, set at $250,000 for all three years, defined the upper limit of costs eligible for reinsurance. The coinsurance rate determined the percentage of costs above the attachment point and below the reinsurance cap that would be reimbursed through the program. Initially, this rate was set at 80% for 2014 and 50% for 2015 and 2016. If reinsurance contributions exceeded payment requests, the coinsurance rate could be increased, up to a maximum of 100%. For example, in 2014, HHS was able to reimburse 100% of eligible claims, and in 2015, the coinsurance rate was increased to 55.1%. Surplus reinsurance funds could be rolled over to the next benefit year. Conversely, if contributions fell short of payment requests, reinsurance payments would be proportionally reduced. Overall, total payments were capped at the total amount collected through contributions.

States choosing to supplement federal reinsurance funds could do so by adjusting program parameters, such as decreasing the attachment point, increasing the reinsurance cap, or raising the coinsurance rate, but they could not make changes that would result in lower reinsurance payments than under the federal parameters.

Data Collection and Privacy: Utilizing Medical Cost Data

Reinsurance payments were based on medical cost data to identify high-cost enrollees. Therefore, HHS or state reinsurance entities needed access to claims data and data on cost-sharing reductions (as reinsurance did not cover costs already subsidized through cost-sharing reductions). In states where HHS administered reinsurance, the same EDGE server data collection approach used for risk adjustment was employed, ensuring that the collection of personally identifiable information was limited to what was necessary for payment calculations. HHS also proposed conducting audits of participating insurers and state-run reinsurance programs.

Similar to risk adjustment, no adjustments to reinsurance payments were made for the first two benefit years (2014 and 2015) as HHS refined the data validation process. Starting in 2016, issuers failing to establish an EDGE server or meet data submission requirements risked forfeiting reinsurance payments. In 2015, the vast majority of participating issuers successfully submitted the necessary EDGE server data.

Payments for the 2014 and 2015 Benefit Years: Program Impact in Practice

In June 2015, CMS announced the 2014 reinsurance program results. Reinsurance contributions in 2014 ($9.7 billion) exceeded payment requests ($7.9 billion), allowing CMS to pay out 100% of eligible claims, totaling $7.9 billion in payments to 437 issuers nationwide. The surplus of $1.7 billion was rolled over to the 2015 benefit year.

This surplus, combined with 2015 contributions, allowed CMS to make an early partial reinsurance payment for the 2015 benefit year in March and April 2016, calculated at a coinsurance rate of 25%. CMS indicated that remaining funds would be paid out later in 2016 as part of the standard payment process.

On June 30, 2016, CMS released the 2015 reinsurance program results. Estimated 2015 contributions ($6.5 billion) were less than payment requests ($14.3 billion). CMS estimated it would make $7.8 billion in payments to 497 of the 575 participating issuers at a coinsurance rate of 55.1%. CMS had collected approximately $5.5 billion in contributions for 2015, with an additional $1 billion expected. Any contributions exceeding $6 billion for 2015 were allocated to the U.S. Treasury. Combined with the $1.7 billion surplus from 2014, CMS estimated approximately $7.8 billion available for 2015 payments. On August 11, 2016, CMS released an analysis suggesting that per-enrollee costs in the individual market remained essentially stable between 2014 and 2015, potentially indicating the stabilizing effect of reinsurance.

Reinsurance payments for the 2015 benefit year were also subject to sequestration at a rate of 6.8%. Similar to risk adjustment, HHS indicated these sequestered funds were expected to become available for payment in fiscal year 2017.

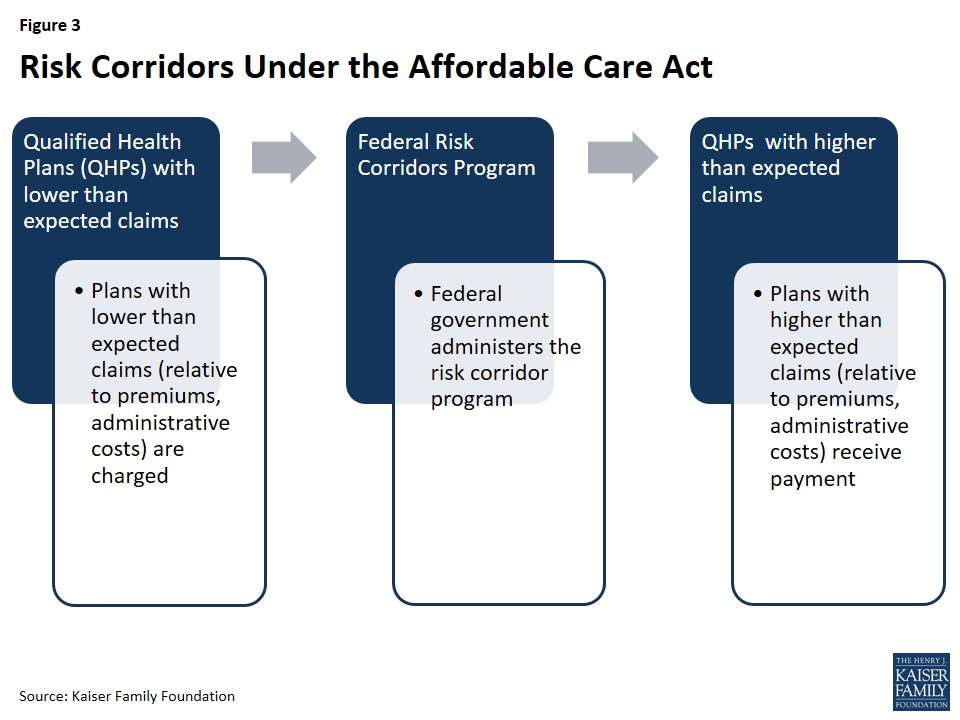

Risk Corridors: Limiting Insurer Gains and Losses

The ACA’s temporary risk corridor program, also in effect from 2014 through 2016, was designed to encourage insurers to participate in the newly established exchanges and to set accurate premiums in the face of market uncertainty. It aimed to protect insurers from extreme financial gains or losses during the early years of the exchanges.

The risk corridor program established a target for exchange-participating insurers to spend 80% of premium revenue on healthcare and quality improvement. Insurers with costs below 97% of this target were required to make payments into the risk corridors program, while those with costs exceeding 103% of the target were eligible to receive payments. The funds collected from insurers with lower-than-expected costs were intended to be used to reimburse plans with higher-than-expected costs.

This program was designed to complement the ACA’s medical loss ratio (MLR) provision, which mandates most individual and small group insurers to spend at least 80% of premium dollars on enrollees’ medical care and quality improvement, or issue refunds to enrollees.

Program Participation: Qualified Health Plans in the Exchanges

All Qualified Health Plans (QHPs), which are plans certified to be offered on the health insurance exchanges, were subject to the risk corridor program. Participation was triggered by performance relative to target spending levels. QHPs offered outside of the exchanges by QHP issuers were also subject to the risk corridors program.

Government Oversight: Federal Administration

The risk corridor program was administered at the federal level by HHS. HHS was responsible for collecting payments from plans with lower-than-expected costs and distributing payments to plans with higher-than-expected costs.

Calculation of Payments and Charges: Target Amounts and Allowable Costs

Each year, each QHP was assigned a target amount for allowable costs, which included expenditures on medical care for enrollees and quality improvement activities, consistent with the ACA’s MLR calculations. Allowable costs were reduced by any cost-sharing reductions received from HHS. If an insurer’s actual claims fell within a band of plus or minus 3% of the target amount (between 97% and 103% of the target), no payments were made into or received from the risk corridor program. In these cases, the plan bore the full financial risk or benefit.

QHPs with claims below 97% of their target amount paid into the risk corridor program based on a tiered structure:

- For claims between 92% and 97% of the target, the payment was 50% of the difference between actual claims and 97% of the target.

- For claims below 92% of the target, the payment was 2.5% of the target amount plus 80% of the difference between actual claims and 92% of the target.

Conversely, QHPs with claims exceeding 103% of their target amount received payments:

- For claims between 103% and 108% of the target, the payment was 50% of the amount exceeding 103% of the target.

- For claims exceeding 108% of the target, the payment was 2.5% of the target amount plus 80% of the amount exceeding 108% of the target.

In response to plan cancellations in the individual market in November 2013, HHS implemented a transitional policy allowing certain plans to be reinstated. To account for the impact of this policy change on the exchange risk pool, HHS modified the risk corridors program in 2015, adjusting the calculation of allowable costs by increasing the ceiling on administrative costs and the profit margin floor by 2%.

The original ACA statute did not mandate that risk corridor payments be budget-neutral. However, subsequent appropriations bills in 2015 and 2016 stipulated that risk corridor payments for 2015 and beyond could not exceed collections from that year, and prohibited CMS from using funds from other accounts to cover risk corridor payments. This effectively made the risk corridors program revenue-neutral. In years where claims exceeded collections, CMS was required to pay out claims pro rata and carry over any shortfalls to be paid in subsequent years before any other claims were paid. HHS indicated that if outstanding claims remained at the end of the three-year program, it would work with Congress to secure funding, subject to appropriations.

Data Collection and Privacy: Alignment with Medical Loss Ratio Reporting

To calculate payments and charges, QHPs were required to submit financial data to HHS, including premiums earned and cost-sharing reductions received. To minimize administrative burden, HHS aligned data collection and validation requirements for risk corridors with those for the ACA’s Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) provision. Audits for the risk corridors program were also conducted in conjunction with audits for the reinsurance and risk adjustment programs to further reduce burden on insurers.

Payments for the 2014 Benefit Year: Significant Shortfalls

On October 1, 2015, CMS announced the 2014 risk corridors program results. Total risk corridor claims for 2014 amounted to $2.87 billion, while insurer contributions totaled only $362 million. As a result, risk corridor payments for 2014 claims were paid out at just 12.6% of claims. CMS anticipated that remaining 2014 claims would be paid from 2015 collections, and any 2015 shortfalls would be covered by 2016 collections in 2017. However, due to the revenue-neutrality requirement imposed by Congress, the risk corridor program ultimately fell far short of its intended purpose of protecting insurers from financial risk, leading to significant financial instability for some participating insurers.

Conclusion: The Legacy of ACA’s Risk Mitigation Programs

The Affordable Care Act’s risk adjustment, reinsurance, and risk corridors programs were strategically designed to operate in concert, mitigating the potential adverse effects of adverse selection and risk selection in the reformed health insurance market. All three programs shared the common goal of promoting stability, particularly in the initial years of market transformation, with risk adjustment intended as a long-term, permanent mechanism.

While these programs had complementary objectives, they differed in their specific approaches. Risk adjustment was designed to counteract incentives for plans to selectively attract healthier individuals and to provide financial support to plans enrolling a disproportionately sicker population. Risk corridors aimed to reduce overall financial uncertainty for insurers, though its effectiveness was significantly curtailed by congressional actions that made the program revenue-neutral, resulting in substantial underfunding. Reinsurance provided direct financial compensation to plans for their high-cost enrollees, effectively subsidizing individual market premiums for a temporary three-year period.

The termination of the temporary reinsurance program in 2016 was anticipated to contribute to premium increases in 2017 and subsequent years. The Affordable Care Act ACA risk adjustment program, however, remains a critical and ongoing component of the ACA, continuing to play a vital role in stabilizing the health insurance market and ensuring fairer competition among insurers by mitigating the financial consequences of risk selection and promoting access to coverage for individuals with diverse health needs.