The landscape of healthcare in the United States is facing a significant challenge: a growing shortage of primary care physicians. This looming crisis, exacerbated by an aging population, increased insurance coverage under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and evolving healthcare demands, necessitates a proactive and strategic response. This article delves into the projected primary care physician shortage, emphasizing the critical role of primary care residency expansion programs in mitigating this gap and ensuring access to quality healthcare for all.

The Projected Primary Care Physician Shortage: A Looming Crisis

Concerns regarding the adequacy of the healthcare workforce are mounting as the US population expands, ages, and gains greater insurance coverage. This confluence of factors contributes to rising healthcare costs, instances of unnecessary treatments, and increased emergency department utilization. The Affordable Care Act (ACA), officially known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, recognized the pivotal role of primary care physicians in addressing these issues. It was envisioned that a robust primary care workforce could effectively manage costs and improve overall healthcare delivery. Initiatives like Family Medicine for America’s Health were launched to bolster the primary care physician pipeline, yet clear guidance on necessary training adaptations remained elusive.

Numerous studies have employed similar methodologies and data sources to forecast the future supply and demand for primary care physicians. A 2008 study by Colwill et al. projected a shortage of 44,000 primary care physicians by 2025. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) echoed these concerns, forecasting a comparable shortage of 46,000 primary care physicians by 2025. In 2013, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) estimated a slightly smaller shortage of 20,400 primary care physicians by 2020. Earlier estimates also pointed to a significant need for 52,000 primary care physicians by 2025, although without a concurrent supply projection.

Previous projections often assumed a static production rate of primary care physicians, basing estimates on overall physician supply growth. For example, HRSA anticipated an 8% increase in primary care physicians by 2020, predicated on the assumption that 31.9% of new physicians would enter primary care. However, this assumption of static production is questionable. Data indicates that only 25.2% of residents graduating between 2006 and 2008 were practicing primary care by 2011. Furthermore, a significant proportion of internal medicine residents, around 40%, do not sub-specialize, yet a growing number of general internal medicine physicians are transitioning out of primary care to become hospitalists.

Innovative primary care delivery models are emerging to enhance healthcare delivery, each influencing physician panel sizes. The patient-centered medical home model, for instance, led the Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound to reduce panel sizes from 2,327 to 1,800. Conversely, some argue that leveraging non-physician clinicians, such as nurse practitioners and physician assistants, could facilitate larger panel sizes. Direct primary care, an evolving model, has been linked to substantial panel size reductions. These shifts are driven by the desire to improve care quality and mitigate physician burnout. Successful implementation of these models could impact both panel sizes and physician retirement ages. While studies suggest an average physician retirement age of around 66, reducing administrative burdens might encourage primary care physicians to extend their careers.

Given these uncertainties and evolving trends, key questions arise: What is the projected primary care physician shortage through 2035, considering retirement rates and current residency production levels? How many additional residency slots, by primary care specialty, are required to address this shortage effectively? And how do variations in retirement age and panel size, reflected in the population-to-primary care physician ratio, influence the projected shortage?

Methodology for Projecting Primary Care Physician Needs

To address these questions, a robust methodology was employed, encompassing baseline physician counts, demand projections, supply estimations, and shortage calculations.

Establishing a Baseline for Primary Care Physicians

Using the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile, the number of primary care physicians was estimated from 2010 to 2014, employing methods consistent with prior research. Physicians in direct patient care were counted if their primary self-designated specialty was family medicine, general practice, general internal medicine, or general pediatrics. General practice, denoting physicians without residency training, is increasingly rare as residency training has become the norm. Geriatricians were classified as either general internists or family physicians based on their residency training, and medicine-pediatrics trained physicians were categorized as pediatricians. These counts were adjusted to account for the AMA’s undercount of retirees and primary care physicians working as hospitalists or in non-primary care settings. Linear interpolation was used to derive 2015 figures for each of the four specialties based on the 2010-2014 trends.

Projecting Physician Demand by Specialty

Current US primary care utilization rates, categorized by patient age and physician specialty, were estimated using the 2010 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). NAMCS was preferred over the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) due to its sampling methodology, which relies on the AMA Masterfile, ensuring accurate specialty counts. MEPS relies on patient-reported specialty, which can lead to inaccuracies, particularly in differentiating between types of primary care physicians.

NAMCS data was used to calculate average office visits to family physicians, general internists, and pediatricians across seven age groups: 0–4, 5–14, 15–17, 18–25, 26–44, 45–64, and 65 years and older. Population projections from the 2010 US Census, which estimated a total population of 370 million (lower than the 2000 US Census estimate of 390 million), were also incorporated.

To project the number of primary care physicians needed by specialty, age- and specialty-specific visit rates were multiplied by projected populations to calculate total visits for each group. These projected visits underwent two adjustments. First, to reconcile NAMCS and AMA Masterfile primary care physician counts, visits were multiplied by the ratio of primary care physicians in the AMA Masterfile to those in NAMCS. Second, to account for increased service utilization by the newly insured population under the ACA, visit numbers were increased by 6.8 million, phased in over 20 years. This figure was derived from the estimated additional primary care physicians needed due to the ACA (7,000 at the lower end) and the mean number of visits. Assuming constant visits per primary care physician at 2015 levels, the required number of primary care physicians was calculated by dividing projected visits to each specialty by the mean visits per primary care physician in 2015. The number of primary care physicians needed solely due to population growth was also calculated by multiplying the projected population growth from 2015 to 2035 by the 2015 ratio of primary care physicians to population.

Assessing the Current Supply of Primary Care Physicians

Data from the American Board of Family Physicians, American Board of Internal Medicine, and American Board of Pediatrics was used to estimate the current annual production of primary care physicians. For internal medicine and pediatrics, resident counts were adjusted to exclude fellows. Counts of osteopathic residency graduates were added for all three specialties. Further adjustments were made based on recent studies of hospitalists, excluding estimated percentages of residents from each specialty likely to become hospitalists. Retirement figures were also adjusted to exclude hospitalists, considering the younger age profile of the hospitalist workforce.

Calculating Shortages and Residency Slot Needs by Specialty

From 2015 to 2035, the accumulated production of primary care physicians, assuming 2015 production levels, was calculated by subtracting retiring physicians from newly produced physicians. The shortage for each year was determined by subtracting the accumulated production from the accumulated primary care need, both overall and for population growth only. The annual additional residents needed was estimated by subtracting the annual net production from the annual additional demand driven by increased need and retirements.

The specialty allocation of needed additional residency slots was determined using three scenarios: (1) slots proportional to the current workforce composition, (2) slots proportional to 2015 production, and (3) a scenario with decreased general internist production (allocating 30% of the combined family physician and general internist share to general internal medicine).

Evaluating the Impact of Retirement Age and Panel Size Variations

A retirement age of 66 years, consistent with AAMC methodology indicating that half of physicians retire by this age, was initially assumed. Using the AMA Masterfile, projections were altered to consider retirement ages of 64 and 68 years. For retirement figures, family medicine and general practice were combined.

In calculating the needed primary care physicians, it was assumed that each physician could handle a specific number of annual visits, using this to derive a population-to-primary care physician ratio (a proxy for panel size). Shortages were also calculated assuming a 10% increase and decrease in this ratio to assess the impact of panel size variations.

Key Findings: A Substantial Primary Care Physician Shortage

Baseline Physician Workforce and Production Estimates

Baseline figures for 2015, interpolated from 2010-2014 trends, estimated 89,054 family physicians, 6,668 general practitioners, 80,810 general internists, and 52,016 pediatricians in direct patient care (Table 1). Medicine-pediatric physicians were included within pediatrician counts for baseline and retirement figures. Baseline production rates, excluding hospitalists, were estimated at 1,869 general pediatricians, 2,412 general internists, and 3,768 family physicians.

Anticipated Retirement Wave of Primary Care Physicians

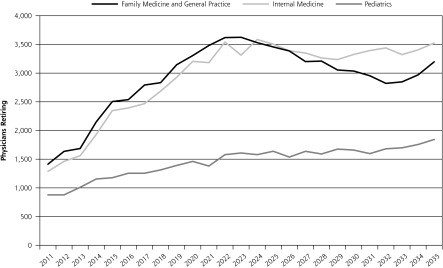

In 2015, it was estimated that 2,504 family physicians and general practitioners, 2,346 general internists, and 1,177 pediatricians were expected to retire. These retirement numbers are projected to increase significantly in the subsequent decade (Figure 1), reflecting the establishment of family practice as a specialty in 1969 and the medical school expansions of the 1970s.

Figure 1. Annual projected number of retiring physicians, by specialty type (2011–2035).

Figure 1

Figure 1

Annual projected number of retiring physicians, by specialty type (2011–2035). aIncludes physicians trained in medicine-pediatrics.

Projected Primary Care Physician Shortages by 2035

Projections indicate that demographic shifts and insurance expansion will necessitate an additional 44,340 primary care physicians by 2035 (increasing from 228,547 to 272,887), with population growth being the primary driver (Table 2). Assuming current production rates (8,049 annually), allopathic and osteopathic graduate medical education will produce 169,029 new primary care physicians between 2015 and 2035. However, physician retirements will outpace production, resulting in a projected shortage of 33,283 primary care physicians by 2035. The annual number of residents needed to address this shortage fluctuates, peaking at 2,710 in 2025 and then decreasing to 1,700 by 2035.

Composition of Additional Physicians Needed

Assuming the ratio of general internal medicine to family medicine mirrors the 2015 workforce composition, and pediatricians maintain their proportion, an annual increase of 1,486 general internal medicine physicians and only 110 family medicine physicians would be required by 2035 (Table 3). A more realistic scenario, aligning with current production ratios, suggests a need for increased annual production of 973 family physicians and 623 general internists. If the trend of declining general internist production persists, hypothetically reaching a 30:70 general internal medicine to family medicine resident ratio, the number of additional family medicine residents needed would rise to 1,117, nearly a 30% increase over current levels.

Impact of Retirement Age and Panel Size Changes on Shortage Projections

Lowering the retirement age to 64 years would escalate the shortage to 38,622, while raising it to 68 years would reduce it to 26,835 (Table 4). Changes in the population-to-primary care physician ratio, reflecting panel size, have more dramatic effects.

A 10% decrease in the population-to-primary care physician ratio would significantly increase the shortage, whereas a 10% increase would substantially reduce it.

Discussion: Addressing the Shortage Through Affordable Care Act Primary Care Residency Expansion Program

These projections, consistent with prior shortage estimations, utilize NAMCS data, population growth, and aging trends to explain demand increases. However, this analysis offers unique insights through its extended projection timeline to 2035, use of 2010 US Census demographic projections (forecasting lower population growth), specialty-specific residency slot projections, and shortage projections accounting for panel size and retirement age variations.

The findings underscore the urgent need for approximately 44,000 additional primary care physicians by 2035 to meet the demands of a growing, aging, and increasingly insured population, maintaining current population-to-physician ratios and retirement rates. Alarmingly, current physician production rates are projected to result in a shortage exceeding 33,000 primary care physicians within this timeframe. Addressing this deficit necessitates adding nearly 2,200 first-year residency positions by 2020, representing a 27% increase.

The scale of this required increase is substantial, highlighting the critical need to sustain current physician-to-population ratios. However, simply expanding traditional hospital-based graduate medical education may not suffice to eliminate primary care shortages. Evidence suggests that expanding community-based graduate medical education, such as teaching health centers and rural training tracks, can enhance the likelihood of graduates entering and remaining in primary care, trained within innovative care models. There is a growing consensus on the need for accountability in public investment in graduate medical education, aligning with the goals of the Affordable Care Act Primary Care Residency Expansion Program.

These projected shortages emerge amidst calls for residency training expansion and transformation. In 2013, the Council on Graduate Medical Education recommended adding 3,000 residency slots, particularly in high-need specialties like family medicine and general internal medicine. The Institute of Medicine also advocated for graduate medical education payment reforms to better support the primary care workforce. Graduate medical education reform, coupled with ACA-driven population-based payment experiments that incentivize new roles for primary care physicians within broader teams, could fundamentally alter these workforce projections. However, the impact of payment reform on primary care physician panel sizes remains debated, and the extent to which graduate medical education reform can radically transform primary care outputs, especially without substantial payment reforms to narrow the primary care-specialty care payment gap, is uncertain. Further research is crucial to determine how new payment models, such as Accountable Care Organizations, will influence primary care recruitment and retention, and how the Affordable Care Act primary care residency expansion program can effectively address these challenges.

While new care models hold potential for enhancing recruitment and retention, they will undoubtedly impact panel sizes, which currently range from 900 to 2,300 patients. Assuming a 2015 population-to-primary care physician ratio of 1,406:1, a 10% reduction translates to shifting 141 patients per physician. Nationwide implementation of such a shift would dramatically exacerbate projected shortages, underscoring the complex interplay between care models, panel sizes, and workforce needs.

Limitations of Projections

These projections are subject to certain limitations. Demand calculations rely on accurate US Census projections and assume constant utilization rates, which may be affected by changes in population health, technology, patient expectations, and evolving primary care models.

Supply projections also involve assumptions that could change. Decreasing hours worked per primary care physician could limit visit capacity. The increasing proportion of women in family medicine, who may work fewer hours, could also impact productivity. Market shifts across primary care specialties and evolving resident interest in primary care could influence supply dynamics.

Obstetrics and gynecology was excluded due to limited primary care interest among practitioners. Non-physician clinicians were not explicitly included, although their potential impact on panel sizes was considered indirectly. While physician assistants and nurse practitioners can contribute to alleviating the shortage, they also face challenges in primary care entry and are increasingly working in hospitals. Furthermore, the analysis does not explicitly address physician maldistribution, a critical factor affecting healthcare access.

Conclusion

The projected primary care physician shortage by 2035 is substantial, necessitating a multi-faceted approach. The Affordable Care Act primary care residency expansion program represents a crucial strategy for increasing the primary care workforce and ensuring adequate access to care. Expanding residency slots, particularly in community-based settings, and reforming graduate medical education payment models are essential steps. Addressing the challenges of retirement, panel size optimization, and evolving care models will further contribute to mitigating the projected shortage. Continued research and policy initiatives focused on strengthening primary care are vital to ensuring a robust and accessible healthcare system for the future.

References

[References] (The same references as in the original article should be listed here, maintaining the original format.)