Adult Day Care (ADC) programs play a vital role in the landscape of long-term care, offering essential services to meet the diverse needs of elderly clients and their families. As the global population ages and the demand for long-term care escalates, ensuring the effectiveness and efficiency of ADC programs becomes increasingly critical. This article delves into the development and application of a comprehensive logic model designed specifically for Adult Day Care Program Evaluation. This model serves as a robust framework for administrators, policymakers, and researchers to assess and optimize ADC services, ultimately leading to improved care and resource allocation.

Understanding the Critical Need for Adult Day Care Program Evaluation

The growing elderly population worldwide is accompanied by a rise in the number of individuals requiring long-term care. Expenditures on long-term care are surging, outpacing other healthcare costs, reflecting the increasing societal need for effective and sustainable care solutions [1]. Concurrently, there’s a growing preference for older adults to remain in their homes and communities for as long as possible, further emphasizing the importance of community-based services like ADC. In countries like Japan, where a significant portion of GDP is allocated to long-term care, there’s heightened scrutiny on the quality and value of services provided. This necessitates rigorous adult day care program evaluation to ensure that these programs deliver optimal care while efficiently utilizing resources.

Adult Day Care centers offer a multifaceted approach to care, encompassing social, preventive, and health-related services. The core objectives of ADC programs often include: (i) fostering social interaction and preventive healthcare measures, (ii) promoting clients’ independence, (iii) addressing the health and daily living needs of attendees, and (iv) providing respite and support for family caregivers, enabling them to maintain employment and personal well-being [3]. The benefits for ADC clients are well-documented, ranging from improvements in physical, cognitive, and social functioning to access to comprehensive care and reduced caregiver burden [3, 4, 5].

However, the inherent heterogeneity of ADC programs, in terms of both client populations and service delivery models, poses challenges to objective evaluation [6]. To address this complexity, a logic model offers a structured and systematic approach to program assessment.

Introducing the Logic Model Framework for Adult Day Care Evaluation

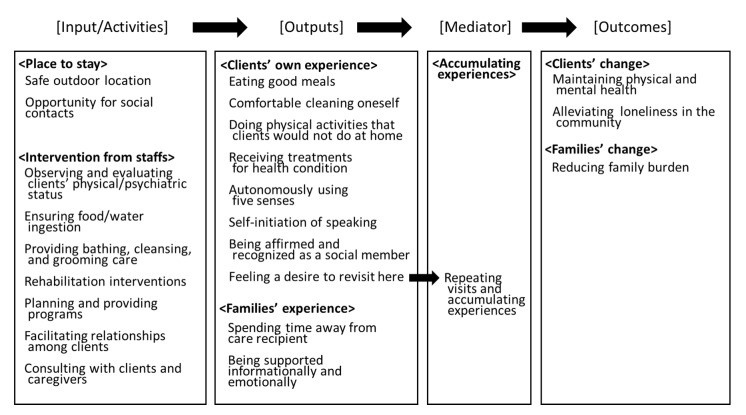

A logic model serves as a visual and narrative representation of how a program is intended to work. It elucidates the relationships between program inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes, providing a clear roadmap of the program’s theory of change [7]. In the context of adult day care program evaluation, a logic model can be invaluable for:

- Clarifying Program Components: Deconstructing the complex elements of an ADC program into distinct categories, such as inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes.

- Identifying Key Relationships: Mapping the cause-and-effect pathways linking program inputs and activities to desired client and family outcomes.

- Guiding Evaluation Efforts: Providing a framework for selecting appropriate evaluation metrics and methods to assess program effectiveness.

- Enhancing Program Planning and Management: Facilitating a deeper understanding of program operations, enabling data-driven decision-making and continuous improvement.

Essentially, a logic model for adult day care program evaluation provides a blueprint for understanding how resources and interventions translate into tangible benefits for clients and their families. It moves beyond simply measuring outcomes to examining the underlying processes and mechanisms that drive program success.

Components of the Adult Day Care Logic Model: Inputs and Activities

The foundation of the ADC logic model lies in its identification of key inputs and activities. These elements represent the resources invested in the program and the actions undertaken by ADC staff to deliver services. In this model, inputs and activities are categorized into two core areas:

Place to Stay

This category encompasses the physical and environmental aspects of the ADC center, emphasizing the creation of a safe and supportive setting for clients. Sub-categories within “Place to stay” include:

- Safe outdoor location: Ensuring accessible and secure outdoor spaces for clients to enjoy fresh air and engage in outdoor activities. This includes considerations for safe transportation to and from the center and for outings.

- Opportunity for social contacts: Designing the physical space and program activities to foster social interaction and engagement among clients. This involves creating communal areas, facilitating group activities, and promoting peer-to-peer connections.

These “Place to stay” inputs are fundamental to providing a secure and stimulating environment that caters to the basic needs and social well-being of ADC clients.

Intervention from Staff

This core category focuses on the actions, services, and support provided by ADC staff. It encompasses a wide range of interventions designed to address the diverse needs of clients. Sub-categories within “Intervention from staff” include:

- Observing and evaluating clients’ physical/psychiatric status: Regularly monitoring clients’ health status to identify any changes or emerging needs. This involves assessments, health monitoring, and communication with healthcare providers.

- Ensuring food/water ingestion: Providing nutritious meals and ensuring adequate hydration for clients throughout the day. This includes catering to dietary needs and preferences and assisting clients with eating and drinking as needed.

- Providing bathing, cleansing, and grooming care: Assisting clients with personal hygiene tasks to maintain their comfort, dignity, and health. This may include bathing, showering, toileting assistance, and grooming.

- Rehabilitation intervention: Offering therapeutic activities and exercises to maintain or improve clients’ physical and cognitive function. This can include physical therapy, occupational therapy, and cognitive stimulation activities.

- Planning and providing programs: Developing and implementing a diverse range of activities and programs to engage clients, promote socialization, and enhance their quality of life. This includes exercise programs, arts and crafts, social events, and cognitive activities.

- Facilitating relationships among clients: Actively fostering positive interactions and relationships among clients. This involves creating opportunities for social engagement, mediating conflicts, and supporting peer support networks.

- Consulting with clients and caregivers: Engaging in regular communication and consultation with clients and their family caregivers to understand their needs, preferences, and concerns. This ensures client-centered care planning and ongoing support.

These “Intervention from staff” inputs are crucial for delivering personalized care, addressing clients’ health and well-being, and creating a supportive and engaging program environment.

Developed Logic Model of Adult Day Care Service

Developed Logic Model of Adult Day Care Service

Components of the Adult Day Care Logic Model: Outputs – Client and Family Experiences

The outputs of the ADC logic model represent the immediate results of the program’s inputs and activities. These outputs are categorized into the experiences of both clients and their families:

Clients’ own experience

This category captures the direct experiences of clients while participating in the ADC program. Sub-categories within “Clients’ own experience” include:

- Eating good meals: Enjoying nutritious and palatable meals at the ADC center. This contributes to clients’ nutritional well-being and overall satisfaction.

- Comfortable cleaning oneself: Feeling comfortable and supported in maintaining personal hygiene while at the center. This promotes dignity and independence.

- Doing physical activities that clients would not do at home: Engaging in physical activity and exercise under supervision in a safe environment, activities they might not undertake independently at home. This enhances physical health and well-being.

- Receiving treatments for health condition(s): Accessing necessary health monitoring, medical, or nursing treatments while at the ADC center. This ensures timely healthcare and management of health conditions.

- Autonomously using five senses: Having opportunities to engage their senses and experience the environment in a stimulating and meaningful way. This promotes sensory engagement and cognitive function.

- Self-initiation of speaking: Feeling comfortable and encouraged to communicate and interact with others spontaneously. This fosters social engagement and reduces isolation.

- Being affirmed and recognized as a social member: Feeling valued, respected, and recognized as a contributing member of the social group at the ADC center. This enhances self-esteem and social connectedness.

- Feeling a desire to revisit here: Experiencing a sense of enjoyment, belonging, and satisfaction that motivates them to return to the ADC program. This is a crucial indicator of program appeal and client satisfaction.

These “Clients’ own experience” outputs reflect the immediate benefits and positive experiences that clients derive from participating in the ADC program on a day-to-day basis.

Families’ experience

This output category focuses on the experiences of family caregivers as a result of their loved one attending ADC. Sub-categories include:

- Spending time away from care recipient: Having dedicated time for respite and personal activities while their loved one is safely cared for at the ADC center. This reduces caregiver burden and promotes their well-being.

- Being supported informationally and emotionally: Receiving information, support, and guidance from ADC staff regarding their loved one’s care and their own caregiving challenges. This enhances caregiver confidence and reduces stress.

These “Families’ experience” outputs highlight the crucial respite and support that ADC programs provide to family caregivers, recognizing their integral role in the caregiving dyad.

The Bridge: Accumulating Experiences for Program Outcomes

Connecting outputs to long-term outcomes is the concept of “Accumulating experiences.” This category acts as a crucial mediator, explaining how the immediate experiences at the ADC center translate into lasting changes for clients and families.

Repeating visits and accumulating experiences

This category emphasizes the importance of consistent and repeated attendance at the ADC program. The logic model posits that positive outputs, particularly “Feeling a desire to revisit here,” contribute to clients’ continued engagement with the program. This sustained participation leads to an accumulation of positive experiences over time, which in turn drives the achievement of desired long-term outcomes. Regular attendance and accumulated experiences are essential for realizing the full potential benefits of ADC programs.

Desired Outcomes of Adult Day Care Programs: Client and Family Changes

The ultimate goals of adult day care program evaluation are to assess the long-term changes and benefits experienced by clients and their families. These outcomes are categorized as:

Clients’ change

This outcome category encompasses the lasting positive changes in clients’ well-being and functioning as a result of ADC participation. Sub-categories include:

- Maintaining physical and mental health: Sustaining or improving clients’ physical health, cognitive function, and overall wellness over time. This includes maintaining activities of daily living (ADLs), preventing functional decline, and promoting mental well-being.

- Alleviating loneliness in the community: Reducing social isolation and fostering social connectedness for clients within their community. This involves building social relationships, maintaining social skills, and preventing social withdrawal.

These “Clients’ change” outcomes represent the long-term impact of ADC programs on enhancing clients’ health, independence, and social integration.

Families’ change

This outcome category focuses on the long-term benefits for family caregivers. Sub-categories include:

- Reducing family burden: Alleviating the emotional, physical, and financial burdens associated with caregiving. This includes reducing caregiver stress, anxiety, and improving their overall quality of life.

The “Families’ change” outcome underscores the critical role of ADC programs in supporting family caregivers and promoting sustainable caregiving arrangements.

Methodology: Developing the Logic Model

The development of this comprehensive logic model for adult day care program evaluation was a rigorous and collaborative process. It drew upon insights from ADC staff and administrators through a multi-stage approach:

- Mini-Delphi Method: Group interviews were conducted with 46 staff members from five ADC facilities using the mini-Delphi method. This iterative process facilitated the identification and categorization of key program elements from the perspective of frontline staff. Staff were asked to identify interventions, experiences provided, client achievements, and reasons for client attendance. Post-It notes were used to encourage individual contributions and mitigate groupthink.

- Administrator Discussions: Follow-up discussions were held with ADC administrators to refine and validate the emerging logic model. Administrators provided feedback on the categories, sub-categories, and the overall structure of the model, ensuring its comprehensiveness and relevance to real-world ADC program operations. Three meetings were conducted, starting with three administrators and expanding to eight in the final validation stage.

- Model Checking and Feedback: The finalized logic model was presented to 46 ADC staff members at a professional development seminar for final feedback and validation. This step ensured that the model resonated with practitioners and accurately reflected the complexities of ADC service delivery.

This robust methodology, combining bottom-up input from staff with top-down validation from administrators, ensured the development of a practical and comprehensive logic model for adult day care program evaluation.

Discussion: Implications for Adult Day Care Program Evaluation

This logic model offers significant implications for enhancing adult day care program evaluation and improving service delivery. By clearly articulating the inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes of ADC programs, the model provides a valuable tool for:

- Program Administrators: The model can guide administrators in program planning, implementation, and quality improvement efforts. It highlights key areas to focus on to maximize client and family benefits and optimize resource allocation. By understanding the interconnectedness of program components, administrators can make informed decisions to enhance service delivery and program effectiveness.

- Policymakers: The logic model provides a framework for policymakers to understand the multifaceted nature of ADC services and to develop informed policies and funding mechanisms that support high-quality, effective programs. It offers a basis for performance monitoring and accountability in the ADC sector.

- Researchers: The model serves as a foundation for conducting rigorous adult day care program evaluation research. It provides a conceptual framework for designing evaluation studies, selecting appropriate outcome measures, and investigating the mechanisms through which ADC programs achieve their impacts. Researchers can use the model to explore the effectiveness of specific program components and interventions.

The model also highlights areas for future research. While the model identifies key inputs and activities, further research is needed to explore the optimal combinations of interventions and environmental factors to maximize ADC benefits. The concept of “person-environment fit” within ADC settings warrants further investigation to understand how to tailor programs to meet the diverse needs and abilities of individual clients. Additionally, future research should incorporate the perspectives of clients and family caregivers directly into the model development and evaluation process to ensure a truly client-centered approach.

One intriguing finding from the administrator discussions was the recognition of the interconnectedness of program elements. Multiple interventions often occur simultaneously, creating synergistic effects. For example, a mealtime can be viewed as an input related to nutrition, social interaction, and even rehabilitation (through the act of eating). This suggests that the combined effect of multiple inputs and activities may be greater than the sum of their individual parts. Future research should explore these synergistic effects and investigate the optimal combinations of ADC interventions to maximize program impact.

Conclusion

This study successfully developed a comprehensive logic model for adult day care program evaluation based on the perspectives of ADC staff and administrators. The model encompasses seven core categories and 23 sub-categories, outlining the key inputs/activities, outputs, and outcomes of ADC programs, with “Accumulating experiences” serving as a crucial mediator.

The logic model underscores the multifaceted nature of ADC services, ranging from basic care needs to psychosocial well-being and self-actualization. It provides a valuable framework for ADC administrators, policymakers, and researchers to evaluate and enhance program quality, ensure optimal care for clients, and promote the efficient use of resources. By adopting a logic model approach to adult day care program evaluation, stakeholders can work collaboratively to strengthen these vital community-based services and improve the lives of elderly adults and their families.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Noriko YAMAMOTO-MITANI, Professor, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo, and Anthony G. Tuckett, Director, Postgraduate Coursework Programs (NMSW), The University of Queensland, for their critical commentary and guidance during this manuscript’s writing process.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.N. and A.K.; methodology, T.N., A.K. and H.M.; validation, T.N., and S.N.; formal analysis, T.N. and A.K.; investigation, T.N. and A.K.; resources, T.N.; data curation, T.N. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, T.N. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, T.N., H.M. and S.N.; visualization, T.N.; supervision, S.N.; project administration, T.N.; funding acquisition, T.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) (grant number: 17K7536) and the Research Grant of the Tokyo Council of Social Welfare 2016.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

[1] Colombo, F.; Llena-Nozal, A.; Mercier, J.; Tjadens, F. Help Wanted? Providing and Paying for Long-Term Care. OECD Health Policy Studies. OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2011.

[2] Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Overview of Long-Term Care Insurance Services in Fiscal Year 2018. 2019. (In Japanese). Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/kaisei/shingi/2r9852000001qbxb-att/2r9852000001qc1j.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2020).

[3] Orellana, K.; Wilber, K.H.; Henderson, V.L. A review of adult day care effectiveness research: 2000–2011. Gerontologist 2014, 54, 220–237.

[4] Weissert, W.G.; Wan, T.T.S.; Livieratos, B.B. Effects and costs of day care services for adults: A summary of findings from the National Adult Day Care Study. Inquiry 1980, 17, 139–149.

[5] Lawton, M.P.; Brody, E.M.; Kleban, M.H. A controlled study of respite service for caregivers of Alzheimer’s patients. Gerontologist 1991, 31, 8–16.

[6] Nadash, P.; Connor, K.; Morrissey, J.P. Adult day care: A review of research and policy issues. J. Aging Soc. Policy 1997, 9, 5–25.

[7] W.K. Kellogg Foundation. Logic Model Development Guide; W.K. Kellogg Foundation: Battle Creek, MI, USA, 2004.

[8] Subirana, M.; Serna, A.; Pujol, R.; Naranjo, J.V.; Juvé-Udina, M.E. Logic model of the effect of nurse staffing on outcomes in hospitals. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2008, 14, 341–349.

[9] Brener, N.D.; Burstein, G.R.; Wheeler, L.; Arkin, R.M. Using logic models in collaborative teen pregnancy prevention efforts. Public Health Rep. 2002, 117 (Suppl. 1), 88–98.

[10] Moore, Z.E.H.; Cowman, S.; Posnett, J. The development of clinical practice guidelines for pressure ulcer prevention: A logic model approach. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2001, 38, 389–401.

[11] Moore, Z.E.H.; Patton, D. Developing a logic model for pressure ulcer prevention in nursing homes. J. Adv. Nurs. 2009, 65, 656–665.

[12] Gaugler, J.E.; Kane, R.L.; Kane, R.A.; Clay, T.; Newcomer, R. Construct validation of a service process scale for adult day care. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 723–733.

[13] Gaugler, J.E.; Kane, R.A.; Kane, R.L.; Clay, T.; Newcomer, R. The longitudinal effects of adult day care on dementia caregivers. Gerontologist 2003, 43, 525–535.

[14] Tanaka, T.; Kikuchi, A.; Yoshikawa, T.; Murayama, H.; Nishida, T. Developing a logic model for multidisciplinary education and training programs in community-based integrated care for older adults in Japan. Geriatr. Gerontol. Int. 2019, 19, 213–220.

[15] Tanaka, T.; Nishida, T. Development of a logic model for evaluating community-based integrated care systems for older adults in Japan. Int. J. Integr. Care 2017, 17, 14.

[16] Biernacki, P.; Waldorf, D. Snowball sampling: Problems and techniques of chain referral sampling. Sociol. Methods Res. 1981, 10, 141–163.

[17] Henningsen, D.D.; Henningsen, M.L.; Eden, J.; Cruz, M.G. Examining the symptoms of groupthink and retrospective reports of group decision-making defects. Small Group Res. 2006, 37, 3–35.

[18] Tsai, L.L.; Tsai, Y.W.; Chou, M.C.; Wang, J.Y. Effectiveness of exercise programs in preventing falls among community-dwelling elderly people with cognitive impairment: A systematic review. J. Formos. Med. Assoc. 2010, 109, 809–817.

[19] De Vries, N.M.; Van Ravensberg, C.D.; Rikkert, M.G.M.; Van Geel, A.C.M.; Esselink, R.A.J.; Nijhuis-Van Der Sanden, M.W.G.; Van Weel, C.; Hopman-Rock, M. Physical activity interventions for older adults with dementia: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 213–225.

[20] Potash, D.A.; Ho, M.Y.; Chan, D.K.; Yancopoulos, J.; Leipert, B.D. The effectiveness of art therapy in improving psychological and physical outcomes for older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontologist 2015, 55, 298–311.

[21] Spector, A.; Orrell, M.; Davies, S.J.; Woods, B. Reality orientation for dementia: A systematic review of the evidence of effectiveness from randomised controlled trials. Gerontologist 2000, 40, 206–217.

[22] Gitlin, L.N.; Reever, K.; Dennis, M.P.; Mathieu, E.; Hauck, W.W. A randomized controlled trial of a home-based intervention to reduce depressive symptoms and improve social activity and self-efficacy in older adults with visual impairment. Gerontologist 2006, 46, 731–737.

[23] Mittelman, M.S.; Ferris, S.H.; Shulman, E.; Steinberg, G.; Levin, B.W. A family intervention to delay nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 1996, 276, 1720–1727.

[24] Aneshensel, C.S.; Pearlin, L.I. Stress, role captivity, and the cessation of caregiving. J. Health Soc. Behav. 1990, 31, 345–356.

[25] Chappell, N.L. Social support and the receipt of home care and institutional care. J. Gerontol. 1985, 40, 47–54.

[26] Kitwood, T. Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First; Open University Press: Buckingham, UK, 1997.

[27] Ihara, M.; Tanaka, T.; Ishikawa, S.; Murayama, H.; Nishida, T. Knitting program for elderly female patients with dementia: A pilot study. Psychogeriatrics 2019, 19, 225–231.

[28] Zarit, S.H.; Stephens, M.A.; Townsend, A.L.; Greene, R.; Mcintosh, M. Family caregiving: Stresses and negative consequences. In Stress and Coping in Later-Life Families; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1990; pp. 153–171.

[29] Crews, D.E.; Zavodny, M. Social isolation, nutritional status, and cognitive function in elderly Appalachian women. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2005, 44, 1–22.

[30] Japan Association of Day Care for the Elderly. The Present Condition and Prospect of Day Care for the Elderly. 2018. (In Japanese). Available online: http://www.nichirekyo.or.jp/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/daycare_hokokusyo_2018.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2020).