1. Introduction

Indigenous Australians face significant health disparities compared to non-Indigenous Australians, with chronic diseases being a major contributor to this gap. Specifically, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples experience poorer health outcomes across their lifespan, and chronic conditions account for approximately two-thirds of the health disparity. This critical issue necessitates innovative healthcare models that can effectively address the unique needs of this population. Recognizing this urgent need, the South Western Sydney Local Health District (SWSLHD) in New South Wales, Australia, developed the Aboriginal Transfer of Care (ATOC) model, a key component of the broader Aboriginal Chronic Care Program Swslhd. This pioneering program aims to improve the transition of care for Aboriginal adults with chronic conditions as they leave the hospital setting and return to their communities.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander individuals living with chronic illnesses encounter numerous obstacles in accessing timely and appropriate healthcare. These barriers range from systemic issues like socioeconomic disadvantage, transgenerational trauma stemming from colonization, and experiences of racism within mainstream health services, to individual and community factors such as family responsibilities often taking precedence over personal health needs. These factors not only hinder access to healthcare but also impact the quality of care received, highlighting the urgent need for culturally sensitive and effective interventions like the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Traditional hospital discharge processes have been increasingly recognized as contributing to suboptimal healthcare outcomes and preventable hospital readmissions, particularly for vulnerable populations. This realization has spurred a greater emphasis on care coordination and seamless transitions of care between hospital and community settings. For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, culturally appropriate and timely transfer of care planning is crucial for maintaining continuity of care and improving health outcomes. This, in turn, contributes to closing the health gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. However, there is a notable gap in research focusing on hospital-based transfer of care initiatives specifically designed for Aboriginal patients with chronic diseases, especially in urban environments, making programs like the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD particularly important to study and understand. Existing research often concentrates on primary care, community-based programs in rural and remote areas, or focuses solely on hospital readmission rates, overlooking the vital experiences of patients and healthcare providers.

New South Wales (NSW), home to a significant portion of Australia’s Indigenous population, has been proactive in developing state-wide initiatives to enhance care coordination for Aboriginal people with chronic conditions. Building upon these broader efforts, the South Western Sydney Local Health District (SWSLHD) conceived the Aboriginal Transfer of Care (ATOC) model, embedded within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. This model operates on the principle that Aboriginal health is a shared responsibility. It employs a multidisciplinary, person-centered, and holistic approach to transfer of care planning, aligning with the Aboriginal concept of health, which emphasizes the interconnectedness of physical, cultural, spiritual, and emotional wellbeing. This holistic view contrasts with a purely biomedical model, recognizing health as deeply intertwined with culture, country, family, community, and the past, present, and future. The Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD and its ATOC model acknowledge the importance of cultural identity, spirituality, and community connections in the wellbeing of Aboriginal people managing chronic conditions.

The ATOC model was initially developed and piloted at Campbelltown Hospital in response to high unplanned readmission rates among Aboriginal patients with chronic diseases. It was subsequently adopted at Liverpool Hospital, both within SWSLHD. This article presents the qualitative findings from a multisite, mixed-methods evaluation of the SWSLHD ATOC model, a key component of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. The study primarily aimed to explore the experiences and perspectives of patients, families, and service providers, and to document and refine the ATOC model for Aboriginal adults managing conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease (excluding dialysis), and asthma. Furthermore, the evaluation sought to enhance the research capacity and translation skills of the Aboriginal managers and staff involved in the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting

The South Western Sydney Local Health District (SWSLHD) encompasses a diverse region of metropolitan Sydney, blending urban, rural, and semi-rural areas. This region is located on the traditional lands of the Dharawal, Gundungurra, and Darug nations. Home to over a million people, SWSLHD includes a significant Aboriginal population, representing 2.1% of the total population. Historical migration patterns have resulted in a diverse Aboriginal community within SWSLHD, drawing people from across NSW and Australia. Notably, a large proportion of the SWSLHD Aboriginal population resides within the Campbelltown and Liverpool Local Government Areas (LGAs).

Campbelltown Hospital, a major metropolitan hospital in SWSLHD, offers a comprehensive range of services, including maternity, palliative care, respiratory, stroke medicine, surgery, and emergency medicine. The hospital has made considerable efforts to create a welcoming and culturally safe environment for Aboriginal people, who constitute 4.8% of the Campbelltown LGA population. Liverpool Hospital, another key facility within SWSLHD, serves as a principal referral hospital, providing acute and tertiary care services to the Liverpool catchment and South Western Sydney residents. Within the Liverpool LGA, the Aboriginal population represents 1.5% of the total population, existing within a highly multicultural area with a significant overseas-born population. Both hospitals are key sites for the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

2.2. ATOC Model within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD

The ATOC model, a core component of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD, is built upon a collaborative approach that integrates cultural expertise from Aboriginal Liaison Officers (ALOs) with clinical expertise from Transfer of Care (TOC) nurses from the Demand Management Unit (DMU). ALOs play a crucial role in supporting Aboriginal patients and their families during hospital stays, while DMU nurses focus on optimizing patient flow. The ATOC team operates across the hospital, augmenting standard transfer of care processes at the ward level. A wide range of hospital clinicians, alongside community-based health and social services, contribute to ensuring Aboriginal patients receive the necessary support for a safe transition back to their communities and primary care providers. The SWSLHD Clinical Nurse Consultant–Aboriginal Chronic Care plays a vital role in consultation and coordination within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

The ATOC model within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD is structured around five key elements:

- Multidisciplinary transfer of care planning: Involving a team of healthcare professionals to create a comprehensive plan.

- Patient and family understanding: Ensuring clear communication and comprehension of the follow-up care plan.

- GP/AMS communication: Informing the patient’s primary care provider (General Practitioner or Aboriginal Medical Service) about follow-up arrangements.

- Community referrals: Organizing referrals to necessary community-based services and supports.

- Medication, equipment, and information: Providing patients with essential medications, equipment, and written discharge summaries before leaving the hospital.

Multidisciplinary transfer of care planning is facilitated through brief, daily “huddles” attended by the ATOC team and representatives from the community-based Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. These huddles serve as a platform for collaborative planning, information sharing, and ensuring patient and family involvement in the care plan. The ATOC team also coordinates referrals to community and social services, such as transport, home care, and housing assistance, as needed. To bridge the immediate post-discharge period, a 5-day supply of new medications is provided, ensuring continuity until GP follow-up. Equipment needs, such as hospital beds or shower chairs, are addressed through an Aboriginal equipment loan pool managed by the Occupational Therapy Department at each hospital, further supporting patients’ transition home within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

The ATOC model was initially piloted at Campbelltown Hospital in early 2016 and subsequently implemented at Liverpool Hospital later that year. While the model has undergone iterative refinement, its core elements have remained consistent, demonstrating the enduring principles of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. Figure 1 visually depicts the ATOC patient journey, illustrating the pathways from the community through the hospital and back to the community, highlighting the various care providers and services involved in ensuring coordinated and safe care for Aboriginal patients across the hospital-community interface. The program logic underpinning the ATOC model is detailed in Appendix A.

Figure 1. ATOC Patient Journey within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD

2.3. Study Design and Ethics

This qualitative study employed a strengths-based, appreciative inquiry approach, recognizing the valuable insights of service users and providers regarding effective practices and contextual factors. Conducted between 2018 and 2019, the study involved university researchers collaborating closely with SWSLHD investigators and the ATOC teams at both hospitals. This collaborative, participatory approach is a well-established methodology in Aboriginal health research and evaluation, aligning with the principles of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. The study incorporated opportunities for research skills transfer and reflective practice throughout the process.

The overall evaluation of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD was Aboriginal-led, from initial conceptualization and research design to knowledge translation and dissemination. It was grounded in the principles of self-determination, equity, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander research protocols. A significant aspect was the Aboriginal leadership within the research team, with the chief investigator and several associate investigators being Aboriginal. Key research partners included SWSLHD, NSW Ministry of Health, and Western Sydney University. The SWSLHD Aboriginal Health Directorate maintains strong partnerships with local Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations and communities. Tharawal Aboriginal Medical Service, having been involved in the ATOC model’s establishment through the Campbelltown Hospital Aboriginal Health Committee, provided support for the study and the ethics application. Ethics approval was granted by the NSW Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Ethics Committee, as well as the SWSLHD and Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committees.

Aboriginal authority over the project was formally exercised through steering committee and working group meetings. Consistent Aboriginal involvement at all stages ensured the qualitative study reflected Aboriginal cultural values and respected local community protocols, integral to the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. The study prioritized Aboriginal voices, included diverse patient demographics, and extended timelines to facilitate appropriate community engagement. Recognizing the importance of local ownership, data collection and initial analyses were conducted separately for Campbelltown and Liverpool Hospitals, treating them as distinct case studies within the evaluation of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

2.4. Data Collection

The qualitative study focused on gathering insights into the experiences and perspectives of Aboriginal patients and their families/carers, ATOC team members, other hospital staff, and community-based service providers relevant to the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Primary data collection methods included key-informant interviews, which were recorded and professionally transcribed, and observational fieldwork. Purposeful sampling, guided by SWSLHD investigators, was employed to ensure a diverse range of perspectives, both positive and negative. ALOs and TOC nurses played a crucial role in promoting the research to patients and staff, who were then formally recruited and interviewed by the research officer. Observations were conducted of ATOC staff in their daily work, including team meetings and case conferences. Documents pertaining to the development and implementation of the ATOC model, such as clinical guidelines, forms, reports, and conference presentations, were also reviewed to provide context to the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Semi-structured interview guides were collaboratively developed for each participant group. Patient and family interviews explored their experiences with hospital discharge preparation and the subsequent impact on their lives, including processes and outcomes. ATOC team members, clinicians, and managers were interviewed about their roles in delivering or supporting ATOC, their views on the model’s strengths and weaknesses, and factors influencing its implementation and sustainability within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. Primary care and community service providers were asked about care continuity and coordination for Aboriginal adults with chronic conditions before and after ATOC implementation. All participant groups were invited to offer suggestions for program improvement and refinement.

The research officer adopted a flexible approach to interviewing, accommodating participant preferences regarding timing and location, and adapting to professional and personal needs, such as rescheduling interviews and providing transport for patients. This flexibility fostered rapport and encouraged open communication. All participants provided written informed consent and were given the opportunity to review their interview transcripts, ensuring ethical and respectful data collection within the evaluation of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

2.5. Analysis

Qualitative data analysis combined inductive and deductive research practices, utilizing the framework method. Findings were organized using the Ngaa-bi-nya evaluation framework, a culturally relevant structure for developing effective, translatable, and sustainable programs for Aboriginal people, aligning with the goals of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. This framework, building upon Stufflebeam’s CIPP model, encompasses four domains: Context (landscape factors), Inputs (resources), Processes (ways of working), and Products (learnings). Transcripts were coded according to categories within this framework using NVivo 12. Coding was performed independently by two non-Aboriginal university researchers, with transcripts compared for consistency and discrepancies resolved through discussion. Interpretation of interview data was supported by ATOC documents and researcher observations, and further discussed within a qualitative working group including Aboriginal researchers and clinicians involved in the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. Analysis of initial interviews informed the development of subsequent interview questions and identification of additional potential informants.

Emerging findings and insights were discussed in qualitative working group meetings and presented to the ATOC teams for verification and to support continuous improvement of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. In a participatory action research component, the Liverpool ATOC team undertook an 8-week trial of a revised ATOC Huddle Form, determining the trial duration and learning objectives, and providing ongoing feedback.

Initial within-case analyses produced detailed descriptions of the ATOC model at each hospital, including operational details and implementation history, which were reviewed with each ATOC team. Subsequent cross-case analysis facilitated the identification of overarching insights and broader lessons applicable to the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD and similar initiatives. Rigour was maintained through double coding, triangulation of data sources and methods, and member checking with the ATOC teams. Regular communication between researchers and SWSLHD investigators ensured Aboriginal perspectives were preserved and prioritized throughout the analysis and interpretation process, upholding the cultural integrity of the evaluation of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

A total of forty-nine individuals participated in interviews – detailed in Table 1. The patient cohort included eight individuals, evenly split between men and women, with ages ranging from their 30s to over 55 years old. The two carers interviewed were female family members, a daughter and a wife. Patient interviews were conducted at various locations, including the Aboriginal patient and family room at Campbelltown Hospital (the Uncle Ivan room), a shopping center, a restaurant, and local libraries, typically a few weeks to months following hospital discharge.

Table 1. Participants in the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD Evaluation

| Informant Group | Campbelltown Hospital | Liverpool Hospital | Other | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATOC team members | 6 | 4 | 0 | 10 |

| Other hospital staff | 10 | 10 | 0 | 20 |

| Community-based service providers | 0 | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| Patients and family/carers | 5 | 5 | 0 | 10 |

| Total | 21 | 19 | 9 | 49 |

Other hospital staff interviewed included managers, ward nurses, allied health professionals (social work, occupational therapy, physiotherapy), doctors (consultant, registrar, GP), and pharmacists. Community-based service providers represented SWSLHD community health programs, Aboriginal Medical Services, South Western Sydney Primary Health Network, and the NSW Department of Housing, providing a comprehensive view of the support network surrounding the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Findings from the cross-case analysis are presented in Sections 3.2, 3.3, 3.4, and 3.5, with participant quotes labeled by participant number, site, and informant group/role. Section 3.6 addresses the contextual factors influencing the model’s implementation and effectiveness within the diverse settings of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

3.2. Resourcing and Ways of Working within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD

Senior managers emphasized the ATOC model’s “resource neutral” nature from a hospital budgeting perspective. The model strategically leverages existing staff, including ALOs and TOC nurses, utilizes current technology, and promotes new collaborative workflows. The establishment of the Aboriginal equipment loan pool was a specific cost borne by SWSLHD to enhance the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Each of the ATOC model’s five elements contributes to effective transfer of care and a positive patient experience within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

In Element 1, multidisciplinary transfer of care planning, ALOs contribute cultural expertise, community knowledge, and insights into patients’ personal needs and family circumstances. TOC/DMU nurses bring clinical expertise and resource knowledge to the team. The following quotes illustrate the complementary roles of ALOs and TOC nurses within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD:

We would look at the home situation, we would look at—if there was a carer, were they managing? We would look at––did the carer need more support? What was going on at home and was there a carer? (P48, Liverpool Hospital ATOC)

The ALO is not a nurse and doesn’t have the clinical knowledge and expertise that senior nurses have. I was able to inform and guide the ALO regarding different medical conditions and the expected outcome, recovery rate and length of stay for the ATOC patients. (P31, Campbelltown Hospital ATOC)

Huddles, the brief daily meetings, serve as the primary platform for information exchange and collaborative transfer of care planning within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. These meetings are most effective when structured, with prepared participants and clear delineation of responsibilities for follow-up actions and reporting.

Having that meeting was the first big step … helping identify the patients, their care needs … facilitating discharging them and making their transition home as best possible. (P1, Liverpool Hospital manager)

Having a quick 15-meeting to go “Right, these are the patients in hospital. I’ve seen this one. I’ve seen that one … This one’s got these problems. This one’s well set up at home. This one just needs transport sorted to get home”. That type of thing. (P31, Campbelltown Hospital ATOC)

Element 2 focuses on ensuring patient and family understanding of the follow-up care plan. Participants highlighted communication breakdowns as a significant issue. The ALO’s role in providing reassurance and clear information was universally valued, fostering a sense of safety and trust. One patient from a regional area emphasized the importance of culturally appropriate communication within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD:

[The ALO] talks to you on a blackfella level, the way they should, especially in the city … He tells the ins and outs of everything, explained everything. (P45, Liverpool Hospital patient)

Service providers emphasized timely communication as crucial for smooth transfer of care, preventing discharge against medical advice, and reducing unplanned readmissions and Emergency Department (ED) presentations, all key health service metrics closely monitored by the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

So, I think communication is the key because I think once it gets to the point of no return, people often will discharge themselves against medical advice. When they don’t really need, we should never have got to that point … And so then they don’t get the optimal care they need, they don’t get the follow up they need. Often they leave without medications so then you’re putting them at higher risks of adverse events. (P28, Campbelltown Hospital ATOC)

Many Aboriginal patients admitted to Campbelltown and Liverpool Hospitals are registered with Aboriginal Medical Services; others have regular GPs. The Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD ensures that patients without primary care providers are connected with one. Patients with chronic conditions are offered referrals to the SWSLHD Aboriginal Chronic Care Program, providing access to care coordination, specialist services, and supplementary support. The holistic approach of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD is underscored by the following quote:

[Aboriginal chronic care] works best when we look at things holistically and when we’re looking at absolutely everything—the psychosocial issues, the social determinants, where people are storing their medication, food—absolutely everything … ATOC really brings those conversations to light and if those conversations come to light very early, means we’re looking at things holistically. (P22, Community-based service manager)

Referrals for home care services and social housing assistance are frequently made. Inadequate housing was repeatedly identified as a factor contributing to chronic ill health, highlighting the social determinants of health addressed by the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Aboriginal patients’ housing and their home environment comes up a lot at our meetings … It’s usually a medical condition, failing heart or lung disease, and they can’t get up and down the steps or its too far to walk or it’s not close to the shops anymore. (P30, Campbelltown Hospital ATOC)

And at home it’s so damp … I’ve got all mould in the house. They’ve come and inspected my house for the last five to seven years and the moulds been there and nothing. ‘Oh, yeah, we’ll fix it up. We’ll fix it up.’ Nothing. And this is why I keep going in hospital, because of the mould too. I can’t breathe. (P13, Liverpool Hospital patient)

Finally, TOC/DMU nurses ensure patients receive necessary medications, equipment, and written patient summary information before discharge. Negotiated within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD, a 5-day medication supply is provided to Aboriginal patients. Provision of equipment like hospital beds and shower chairs prior to discharge reduces patient and family stress and lessens the burden on primary care providers, demonstrating the comprehensive support offered by the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

A hospital bed is one of the biggest things that needs to be organised before they go home to make them comfortable in their bed. Equipment needs to be organised … so that [there is] less stress for the family when they go home”. (P18, Community-based service provider)

3.3. Outcomes and Impact of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD

The pilot study at Campbelltown Hospital demonstrated an immediate positive impact, with a sustained decrease in unplanned readmissions and ED presentations for Aboriginal patients, alongside improved Aboriginal patient identification in ED. After 2-3 years of operation, the qualitative study confirmed enhanced care coordination and improved transfer of care experiences as key outcomes of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. ATOC patients reported feeling safer and more supported during their transition home, and ATOC staff expressed satisfaction in collaborative teamwork contributing to shared goals. Organizational and system-level benefits included increased trust in health services and strengthened inter-service partnerships facilitated by the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

For Aboriginal individuals managing chronic conditions, particularly those with frequent hospitalizations, a sense of safety can be elusive. Patients, especially those experiencing acute events like heart attacks, found the ATOC team’s support and ALO’s clear communication regarding procedures and follow-up arrangements reassuring. The Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD directly addresses these anxieties:

I had a lot of support there which was good because that’s what you really need. You’re in foreign place. You’re scared. You don’t know what’s gonna happen. (P13, Liverpool Hospital patient)

It’s just a bit scary coming out of hospital trying to, after what’s happened to you … Because most of the time I’ve been in there it’s life-threatening, it gets scary. It gets scary in there and it’s scary out here. (P43, Campbelltown Hospital patient)

It just makes me feel at ease, really at ease … I’ve got someone there to help me. I’m not on my own with the system. (P41, Campbelltown Hospital patient)

Improved communication fostered by the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD increases awareness among healthcare staff, particularly TOC/DMU nurses who may have limited prior experience in Aboriginal health. Engaging in dialogue with patients and families helps them understand individual needs and risks. For Aboriginal patients, positive experiences with ATOC during hospitalization and discharge can build trust, improve engagement with health services, and reduce instances of self-discharge.

We had one Elder that came in that it took a while for him to get into hospital. However, once he was here and we did speak to him and we did support his progression here in the hospital. Once he was discharged, he went home happy and we got the feedback from [the ALO] that he has been trying to encourage other Aboriginals that he knows that are very sick to come in to hospital because we will help them and that we are providing a good service and acknowledging their culture and supporting their culture. (P29, Campbelltown Hospital ATOC)

ATOC staff derive job satisfaction and motivation from feeling part of a team and witnessing the positive impact of their work in “closing the gap”. Acknowledging the multifaceted influences on health, staff reported numerous positive outcomes stemming from patient-centered, multidisciplinary care planning and coordination across the hospital-community interface facilitated by the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

I think it’s very necessary and it helps across the board of the hospital’s operations in terms of patient flow, patient satisfaction, and in a way, staff satisfaction. I always feel really happy when we have a successful ATOC case that doesn’t represent to hospital and it’s like ‘Wow! We’ve done everything that we can for you and you’re managing very well at home. You’re not engaging all of these high-risk behaviours and all that stuff’. (P49, Liverpool Hospital ATOC)

Positive experiences with ATOC have spurred new Aboriginal health collaborations and strengthened existing partnerships and systems within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. Shared-care meetings for complex patients were highlighted as particularly beneficial. The following comment from a Housing officer illustrates the perceived effectiveness of the model’s interagency collaboration:

[Department of] Housing are getting phone calls earlier from staff in the hospitals about saying ‘We have someone came in last night that looks like they’re going to be in here for the week. They’re homeless. Can we get some information about their housing?’ So that’s been really beneficial and it’s been vice versa when I know that I’ve had, especially homeless clients, because they’re so transient when I know that they got into hospital, I can call that hospital and say ‘These are the issues. Can we try to get a care coordination while they’re there, before they leave hospital as well?’ (P24, Community-based service provider)

3.4. Challenges Faced by the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD

Operating within a busy hospital environment with constant pressures on bed availability and patient flow presents inherent challenges to ensuring comprehensive support for all Aboriginal patients with chronic conditions. Key challenges identified within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD include staff availability, patient identification, managing complex patient needs, and addressing broader cultural safety concerns throughout the hospital.

ATOC’s operational hours, typically 9 am to 5 pm on weekdays, limit service delivery and patient access outside of these times. The program relies on standard hospital information systems and communication tools, which can be limiting. Incomplete identification of Aboriginal patients, especially those with chronic conditions, remains a persistent issue. The transition from paper-based records to electronic systems necessitates consistent and accurate data entry by clinicians. While ATOC is designed as a “short and sharp” intervention, it is not ideally suited for highly complex patients requiring extensive time and resources. Identifying and prioritizing the needs of these complex cases and ensuring comprehensive support remains a challenge for the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Experiences of poor treatment of Aboriginal patients within the hospital system were raised by both service users and providers, highlighting ongoing cultural safety concerns that the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD seeks to address:

I don’t think they treat the Aboriginal people the way they should be treating them and that’s why a lot of Aboriginal people will not go to hospital. They will not go to a doctor and they will not go to a hospital because the way they’re treated. (P13, Liverpool Hospital patient)

Many patients have historically not had positive experiences with hospitals. [We try] to ensure ATOC patients feel comfortable and safe; this encourages the patient to remain in hospital until they are well enough to go home and be compliant with medications and follow-up. (P31, Campbelltown Hospital ATOC)

Building trust and rapport with Aboriginal patients who may have had negative past experiences with government health services requires sustained effort. Addressing the lack of cultural safety and misunderstandings around the concept of “equity” versus “equality” among some staff remains a significant challenge for the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. Instances of discharge against medical advice were linked to patients feeling unheard or having their needs disregarded.

3.5. Critical Success Factors of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD

The ATOC model’s success is underpinned by goodwill, shared purpose, and a pragmatic, problem-solving approach. Critical success factors for the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD include robust governance structures with joint cultural and clinical leadership, and strong, sustained relationships among individuals and teams across service delivery, organizational, and system levels.

ATOC operates within a broader governance framework encompassing multiple Aboriginal health initiatives in SWSLHD. District-level leadership is shared between the Aboriginal Health Directorate and Nursing. Each hospital has an Aboriginal Health Committee, with ongoing executive support. A shared understanding of ATOC’s rationale and processes is crucial. Senior managers emphasized the commitment from both management and staff to the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD:

I think the fact that there’s a general commitment within this agency that Aboriginal health is a priority has helped us push a lot of this along. (P17, SWSLHD manager)

If you develop the systems and some good governance and develop what’s important, you can then start to develop your culture around [that] … It’s the culture and your staff, your staff commitment to those processes that will keep them going. (P33, Campbelltown Hospital manager)

Effective transfer of care is facilitated by a skilled and culturally competent workforce and a collaborative approach. Within the core ATOC team, ALOs provide cultural expertise and TOC/DMU nurses contribute clinical expertise. Having both female and male ALOs is considered desirable to uphold cultural gender protocols, provide peer support, and share workload within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. Cultural training for non-Aboriginal ATOC staff is essential, broadening their understanding of social determinants of health and cultural perspectives.

You can’t work with my people if you don’t know how to. (P14, Liverpool Hospital patient)

We know how to communicate … We now know how to address sensitive issues. We know how to provide the proper support … When a patient or a person feels supported, they then cooperate with the rest of the planning of their stay here. So I think the fact that we’re now, one, culturally aware; two, have [the ALO] and [the ALO] has us to support [them] with the medical side of things provides effective patient care. (P30, Campbelltown Hospital ATOC)

Having this ATOC team for our patients is just another stepping stone for our people. (P26, Campbelltown Hospital ATOC)

However, a small ATOC team alone is insufficient. The success of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD relies on active participation from other hospital staff and managerial support, as well as effective interagency partnerships. Partnerships with Aboriginal Medical Services and the NSW Department of Housing have been particularly vital. Access to suitable housing is a critical component of safe hospital discharge and maintaining health at home. Through partnerships and networks, staff can advocate for patients and families. The ability to escalate issues and leverage wide networks is particularly important when resources are limited, emphasizing the need to “utilise everything that’s out there” within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

3.6. Contextual Similarities and Differences in Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD Implementation

Both study hospitals demonstrated a commitment to culturally responsive care and recognized the need for an Aboriginal-specific transfer of care protocol and the crucial role of ALOs within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. However, identifying Aboriginal patients, particularly adults with chronic conditions, remained an ongoing challenge due to incomplete or inaccurate records at both sites. Staffing delays resulted in prolonged vacancies in ALO positions. Integrating ATOC into routine care for the target population was more challenging at Liverpool Hospital, a principal referral hospital with higher nursing staff turnover, greater patient diversity, and proportionally fewer Aboriginal patients. The hospital environment at Liverpool was perceived as less welcoming for Aboriginal people compared to Campbelltown. Furthermore, the strong sense of ownership evident at Campbelltown Hospital, where the model originated, was less pronounced at Liverpool. These contextual differences suggest that tailored implementation strategies and additional resources are needed to effectively implement and sustain the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD across diverse hospital settings.

4. Discussion

Mainstream health services often struggle to adequately meet the complex needs of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients with chronic conditions. The SWSLHD ATOC model, a key initiative within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD, emerged as a local solution to this widespread issue. This holistic care model effectively integrates cultural and clinical expertise and leverages existing resources to facilitate safe and supported transfer of care for Aboriginal adults with chronic conditions leaving hospital. The qualitative evaluation demonstrates that the ATOC model is well-received by Aboriginal patients, families, and community-based service providers. It enhances the patient journey, improves patient and family experiences, builds trust in health services, and contributes to staff satisfaction. Importantly, ATOC implementation has been achieved with minimal additional hospital resources within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. Initially designed for chronic conditions, the model has been successfully extended to cancer and palliative care, and service providers and managers see potential for further expansion to areas like mental health and maternity services.

The study’s findings regarding challenges and critical success factors align with previous reviews of Aboriginal transfer of care initiatives in Australia. Commonly identified barriers include system complexity, unclear pathways, and a lack of a well-trained and coordinated workforce with defined roles. Local referral pathways and the crucial role of Aboriginal Health Workers were consistently highlighted as enablers. This study further emphasizes the broader issue of cultural safety and its profound impact on Aboriginal people’s experiences within hospital care, and how the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD endeavors to address these systemic issues.

Globally, Indigenous peoples continue to experience racism, including systemic racism, which negatively impacts their health. Long-standing structural inequities persist in healthcare settings, eroding trust in health systems. Cultural security is recognized as a fundamental element of effective services for Indigenous populations worldwide. Improving cultural security requires ongoing effort and commitment. Studies in Western Australia indicate that a significant proportion of health and social service providers do not perceive their services as fully culturally secure, highlighting the need for continued improvement through employing Aboriginal staff and providing enhanced cultural awareness training for non-Aboriginal staff, key strategies employed by the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Cultural competency, safety, and security are essential at both individual practitioner and organizational levels to achieve equitable healthcare delivery. Cultural training, particularly the Respecting the Difference framework used by NSW Ministry of Health and SWSLHD, is a vital component. The unique contributions of the Aboriginal health workforce, including community connections, cultural and spiritual knowledge, and culturally appropriate healthcare delivery, are well-documented. Research consistently highlights the indispensable role of ALOs in improving communication, care continuity, and reducing discharge against medical advice for Aboriginal patients. The ATOC model, central to the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD, effectively leverages the expertise of ALOs and TOC nurses to address the cultural, clinical, and psychosocial dimensions of patient transfer of care.

Beyond the ATOC model itself, the SWSLHD Aboriginal governance framework, encompassing all district hospitals and related Aboriginal health initiatives like the SWSLHD Aboriginal Chronic Care Program, is a significant strength. This framework, along with partnerships with Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations, has facilitated the ATOC model’s development and growth, and provides the foundation for the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. ATOC aligns with the He Pikinga Waiora framework, which emphasizes grounding implementation science for Indigenous communities in Indigenous knowledge, participatory approaches, and systems thinking. The ATOC model implementation and evaluation effectively incorporate all four elements of He Pikinga Waiora: a culture-centered approach, community engagement, systems thinking, and integrated knowledge translation, demonstrating best practices within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

The participatory nature of this qualitative study yielded immediate benefits, strengthening the research and research translation capabilities of Aboriginal managers and staff involved in the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. Steering committee and working group meetings fostered mutual learning. Data collection provided ATOC team members with opportunities for reflective practice, enhancing their understanding of the model and their respective roles. The Liverpool Hospital ATOC team refined their ATOC Huddle Form through a participatory action research trial, resulting in improved information exchange. The research validated existing practices at Campbelltown Hospital and elevated the team’s profile. The ALO role was reinforced, and Aboriginal patient and carer voices were amplified. Connections with community-based health and social services were strengthened. SWSLHD investigators gained research expertise, while Aboriginal Health managers gained experience in leading a large-scale evaluation. ALOs developed a “better appreciation of research” and valued “sharing what we’re doing with other services” within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Evaluation outputs include educational posters and a toolkit designed to support ATOC implementation and facilitate transfer to other settings. These resources emphasize teamwork, support structures, and partnerships. The posters incorporate Aboriginal design and artwork, and one poster features a ‘cultural yarn’ highlighting knowledge sharing across Aboriginal lands. The Aboriginal Transfer of Care (ATOC) Model Toolkit, a key deliverable of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD, includes an orientation package, role descriptions, case studies, and a structured ATOC Huddle Form.

5. Strengths and Limitations

This qualitative study’s strengths lie in its multi-site design within a metropolitan Sydney Local Health District, prolonged engagement, triangulation of data sources and methods, and member checking. Purposeful sampling ensured diverse viewpoints and experiences were captured. Aboriginal perspectives were prioritized throughout analysis and interpretation, ensuring cultural integrity within the evaluation of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. The study provided valuable insights into program processes, service user and provider experiences, and outcomes. It accounted for the ATOC model’s evolution and implementation variations across Campbelltown and Liverpool Hospitals. While transferability to other settings requires caution, the findings offer valuable learnings applicable to similar contexts beyond the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD. Given the complexity of patient needs and the involvement of multiple agencies, outcomes cannot be solely attributed to ATOC.

6. Conclusions

This collaborative research project examined the impact of an innovative model of care, the ATOC model within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD, which leverages mainstream and Aboriginal health resources to improve hospital-to-primary care transitions for Aboriginal adults with chronic conditions. The multi-site evaluation provides evidence that a holistic model, integrating cultural and clinical expertise and partnering with Aboriginal community organizations, can enhance care coordination and safety for Aboriginal patients across the hospital-community interface. Contextual factors, including organizational and environmental elements, are crucial considerations in program design, implementation, and evaluation. Further research is needed to fully understand the contribution of transfer of care initiatives to achieving equitable healthcare and improved health outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians, building upon the promising results of the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Acknowledgments

With respect, we acknowledge the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples of Australia as the traditional custodians of this land. We particularly acknowledge the Dharawal, Gundungurra, and Darug nations, the traditional custodians of South Western Sydney, and pay our respects to Elders past, present, and future. We thank the steering committee and working groups, comprising representatives from SWSLHD, Nepean Blue Mountain Local Health District, NSW Ministry of Health, and Western Sydney University. Anau Speizer, SWSLHD Aboriginal Chronic Care Program Clinical Nurse Consultant, provided invaluable assistance. Karen Beetson and Amanda Jane Copeman created the ATOC poster designs and artwork. We extend our deepest gratitude to the Aboriginal patients and carers who shared their stories and to the ATOC team members at both hospitals for their dedication to the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

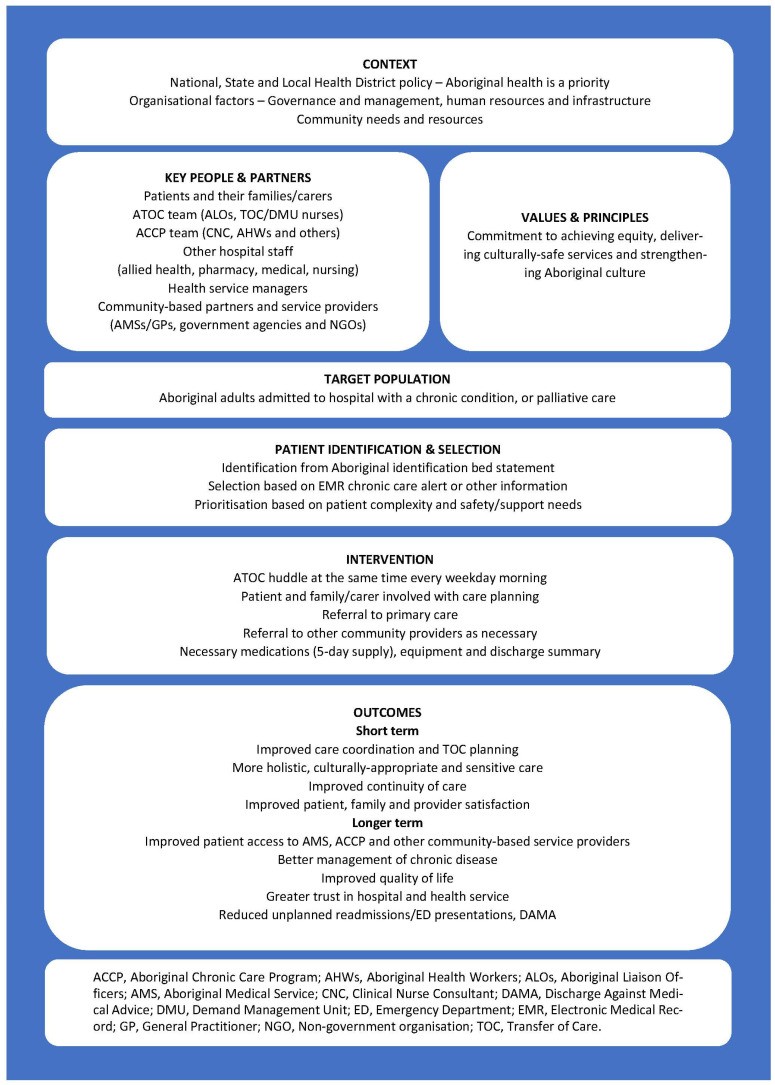

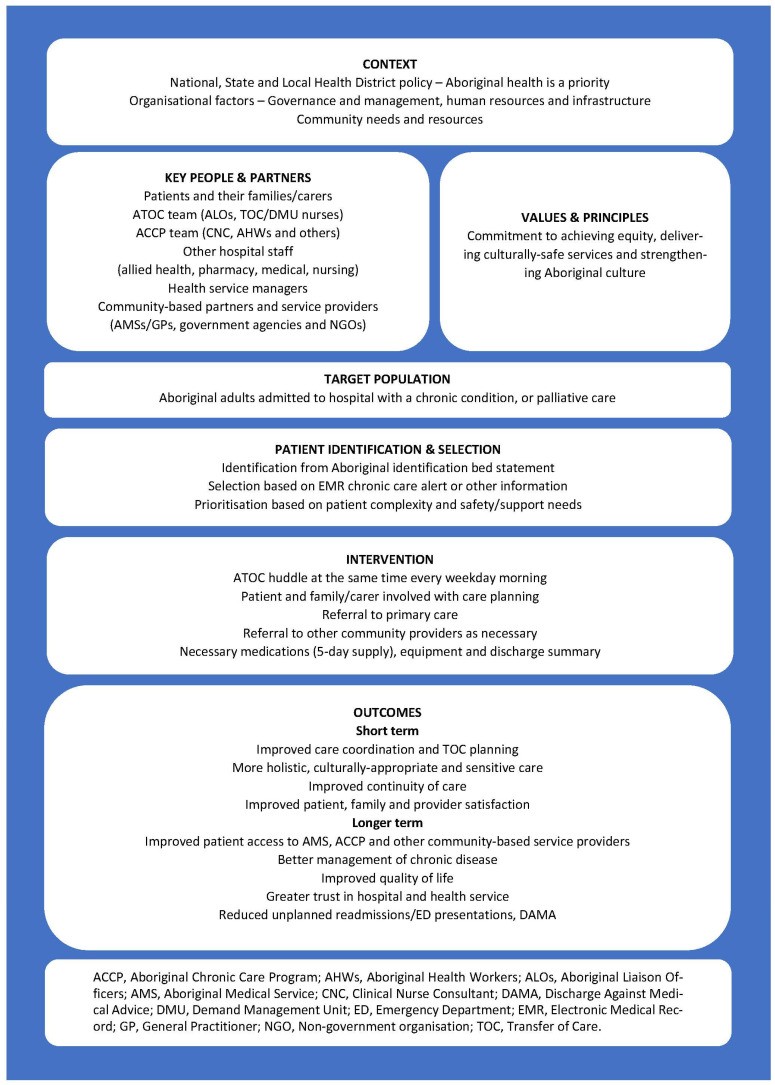

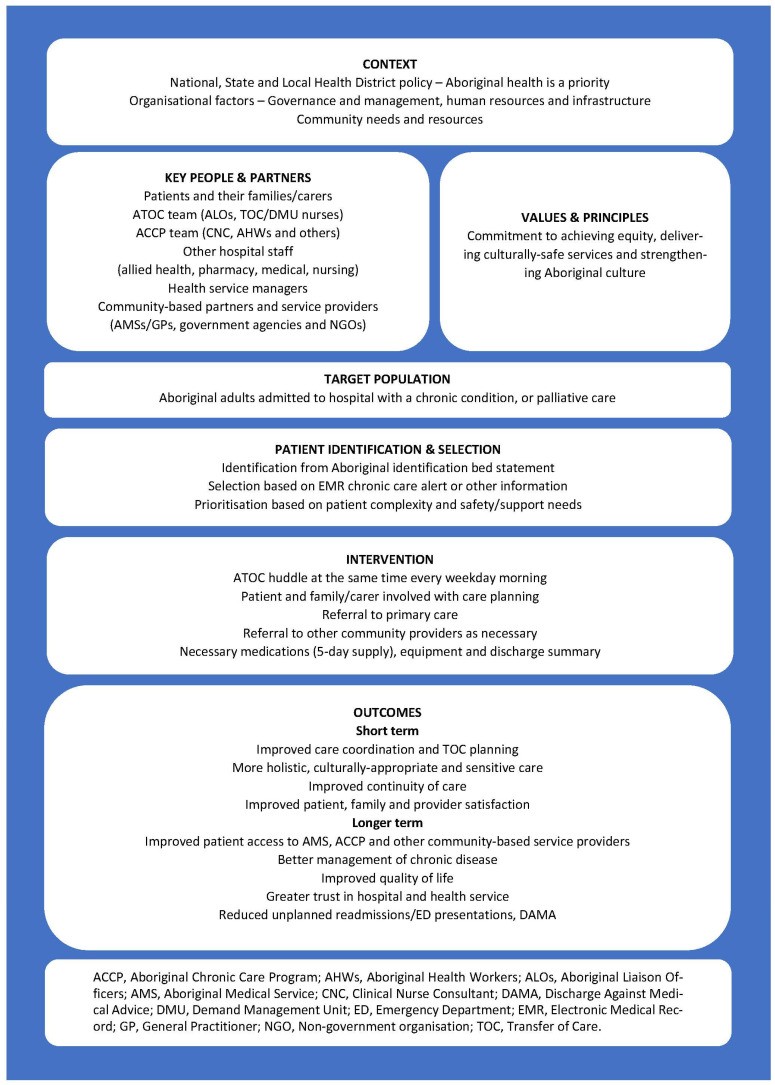

Appendix A

Figure A1. Program Logic of the Aboriginal Transfer of Care (ATOC) Model within the Aboriginal Chronic Care Program SWSLHD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, I.B., B.J., N.J.; Methodology, I.B., L.N., R.B., G.B., K.B., N.J.; Transcript validation, I.B., L.N.; Formal Analysis, I.B., L.N.; Investigation, I.B., L.N., R.B., G.B., K.B.; Resources, R.B., G.B., K.B., N.J.; Data Curation, I.B., L.N.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, I.B., L.N.; Writing—Review and Editing, I.B., L.N., R.B., G.B., K.B., B.J., N.J.; Supervision, I.B., K.B., N.J.; Project Administration, I.B., L.N.; Funding Acquisition, N.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The ATOC model evaluation was funded by the NSW Government Office of Health and Medical Research under the Translational Research Grants Scheme. The article processing charge was funded by Western Sydney University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approvals were obtained from the Aboriginal Health and Medical Research Council Ethics Committee (Ref: 1330/17AH&MRC) and the SWSLHD Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/17/LPOOL/409), with external recognition from Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee (RH12861).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The qualitative data are not publicly available as they contain information that could potentially re-identify individuals. The Aboriginal Transfer of Care (ATOC) Model Toolkit is available from Nathan Jones ([email protected]).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[List of references from original article – not repeated here for brevity]

Associated Data

Data Availability Statement

The qualitative data are not publicly available as they contain information that could potentially re-identify individuals. The Aboriginal Transfer of Care (ATOC) Model Toolkit is available from Nathan Jones ([email protected]).