Abstract

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods stand as the most effective reversible options for preventing adolescent pregnancy, a crucial aspect of adolescent health care. Despite endorsements from major medical bodies and rising usage, LARC adoption among US teens remains lower than short-acting methods. Effective communication is key to addressing barriers and improving LARC uptake. This review explores adolescent LARC use, barriers, and communication strategies, advocating for adolescent-centered, shared decision-making approaches rooted in reproductive justice and the health belief model. Moving away from presumptive counseling towards empowering adolescent reproductive autonomy and fostering open parent-adolescent communication is paramount for successful reproductive health programs. Innovative strategies, such as incorporating teen theater into adolescent health care communication programs, can further enhance engagement and understanding of these critical health choices.

Keywords: long-acting reversible contraception, LARC, Contraception, adolescent, pregnancy prevention, birth control, communication, contraception counseling, Adolescent Health Care Communication Program Teen Theater

Introduction

Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods, including levonorgestrel (LNG) and copper (Cu) intrauterine devices (IUDs), and subdermal contraceptive implants (etonogestrel or levonorgestrel-based), are recognized as the most effective reversible forms of birth control. Leading medical organizations like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) support their safety and suitability for adolescents.1,2

The decline in adolescent sexual activity coupled with increased use of effective contraception, notably LARC, has significantly reduced adolescent pregnancy rates in the US.3 However, despite this progress, LARC uptake among adolescents still lags behind short-acting methods.4 Disparities in LARC adoption persist across racial, ethnic, and age groups, compounded by practical limitations.5,6 Historical misconceptions regarding LARC safety and appropriateness for adolescents may hinder effective clinical counseling and provision. A comprehensive understanding of LARC history, mechanisms, and current adolescent usage patterns, both in the US and globally, is vital for healthcare professionals. This knowledge empowers them to offer informed guidance, address concerns, and facilitate contraception decisions that align with the preferences and values of adolescents and their families.

Adolescents have unique concerns about initiating and continuing LARC compared to adult women. Understanding factors influencing adolescent LARC uptake, including device characteristics, acceptability, anticipated discomfort, myths, and cultural nuances, is crucial for effective contraceptive counseling.7 Identifying specific adolescent barriers, such as provider misconceptions, legal and practical obstacles, cost, access, and confidentiality, is essential to refine LARC communication strategies.8

It’s critical to balance LARC benefits with empowering adolescent autonomy through patient-centered, shared decision-making communication. Provider communication should encourage ongoing dialogues about sexual health between adolescents and their parents. While “LARC-first” counseling might increase uptake, it risks coercion and perpetuating historical reproductive injustices by overemphasizing LARCs at the expense of other methods.8 Reproductive justice principles advocate for adolescent women’s right to choose LARC, non-LARC methods, or no method at all, and to have LARC devices removed upon request.8 Therefore, evidence-based communication strategies for LARC counseling, within a reproductive justice framework and the health belief model, are essential. This includes practical clinical guidance to avoid common counseling pitfalls and examples of best practices in LARC communication.

This review aims to equip clinicians with practices for improved LARC communication, counseling, and adherence by providing context and insights into factors influencing adolescent LARC use. First, we present an overview of LARC history, mechanisms, and adolescent usage trends in the US and globally. Next, we explore factors affecting adolescent LARC uptake, continuation, and barriers. Finally, we characterize communication practices that support adolescent-centered, shared decision-making, encourage parent-adolescent sexual health communication, and empower adolescent LARC uptake, continuation, and adherence for those who choose this method. Furthermore, we propose that innovative approaches, such as adolescent health care communication programs incorporating teen theater, can play a significant role in enhancing engagement and understanding around adolescent reproductive health.

Overview of LARC History, Mechanism of Action, and Adolescent Usage Patterns in the United States and Globally

Intrauterine Device History and Current Models

Public perception of IUD safety and appropriateness in the US has undergone significant shifts. First-generation copper (Cu) and levonorgestrel (LNG) IUDs were introduced in the US in 1968. However, the Dalkon Shield IUD in the 1970s, with its multifilament string prone to infections, severely damaged public trust.9 Its withdrawal from the US market in 1974 negatively impacted IUD perception, acceptability, and usage.10 By 1995, IUD usage among US women of reproductive age had plummeted to 1–2% among non-Hispanic White women and near 0% among non-Hispanic Black women.10,11

Current IUD models in the US include the copper IUD ParaGard (introduced in 1988, approved for 10 years) and four hormonal IUDs. Mirena, the oldest hormonal IUD (2001), contains 52 mg LNG, releasing ~20 mcg/24 hours.12 Initially approved for five years, its effectiveness duration has been extended to 8 years for pregnancy prevention based on long-term data.13 Three newer LNG-IUDs—Skyla (3 years, 13.5 mg LNG), Kyleena (5 years, 19.5 mg LNG), and Liletta (8 years, 52 mg LNG)—emerged between 2013 and 2016, varying in dose and duration.14 Unlike Mirena, initially approved based on data from women who had been pregnant, these newer IUDs were studied and approved for both nulliparous and parous women. Liletta’s FDA approval trials notably included adolescents aged 16 and 17, while other IUD trials typically included women 18 and older.15 Skyla and Kyleena feature narrower 3.8mm insertion devices (compared to Mirena’s 4.4mm and Paragard/Liletta’s 4.75mm). Despite these minor size differences, all devices are safe for nulliparous women, including adolescents.16

Hormonal IUDs and various Cu-IUD models are available globally, but accessibility and cost vary significantly.17 Some countries offer IUDs and implants free of charge, while others may require patients to pay hundreds of US dollars.17 Global initiatives to improve LARC access and affordability in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) include public-private partnerships for manufacturer donations of unbranded LARC devices and the development of a lower-cost hormonal IUD, Avibela, by a non-profit pharmaceutical company, available in select LMICs.18

Subdermal Implant History and Current Models

Norplant, the first subdermal implant in the US, was approved in 1991. Despite initial popularity, side effects and removal difficulties led to its decline, and sales ceased in the US in 2002.10 Furthermore, Norplant was implicated in reproductive rights coercion, particularly targeting poor, minority, and incarcerated women. Some states even proposed legislation to incentivize or mandate Norplant use for women on public assistance or convicted of crimes.10,19 This history is especially relevant for populations with past or ongoing reproductive coercion, such as forced sterilization of minority women in the US.10 Reproductive freedom and autonomy must be central to contraceptive discussions to prevent perpetuating historical reproductive injustices.20

Nexplanon, the current subdermal implant in the US, was introduced in 2010. It improved upon Implanon (1998), the previous single-rod model, with a better insertion device and radio-opacity.14 While initially approved for three years, research supports efficacy for four years or more.13

Internationally, two LNG-releasing subdermal implants exist, each with two rods containing 75 mg LNG (150 mg total).21 Research suggests different LNG release rates, recommending a maximum duration of 5 years for Jadelle (Finland) and 3 years for Sino-implant (II) (China, globally distributed as Levoplant).21

LARC Mechanism of Action and Medical Benefits

LARC methods are the most effective reversible contraception, with failure rates under 1%.22 LNG-IUDs thicken cervical mucus, impair sperm mobility, and alter the uterine environment, reducing gamete viability and fertilization likelihood.23 Cu-IUDs create inflammatory and biochemical challenges to sperm mobility, gamete viability, and fertilization in the uterus.23 Ovulation is unaffected by Cu-IUDs, while LNG-IUD users may experience anovulation.24 Etonogestrel subdermal implants suppress ovulation.1 LARC methods do not prevent implantation of fertilized embryos.23

Beyond contraception, LARC offers medical benefits. The 52 mg LNG-IUD (Mirena) reliably reduces or stops menstrual bleeding, unlike lower-dose LNG-IUDs (Skyla) or Cu-IUDs, where regular menses are more common. Progestin-containing LARCs typically improve dysmenorrhea.25 LNG-IUDs have a lower potential for drug interactions due to limited systemic hormone exposure compared to other hormonal contraceptives.[25](#cit0025] Cu-IUDs provide highly effective nonhormonal contraception for women with hormone contraindications, though they may worsen bleeding and cramping.25 Low medication interaction risk and lack of adverse mood effects in both Cu-IUDs and progesterone-containing LARCs make them valuable options for women with mood disorders like depression and anxiety, who are at higher risk of non-adherence to short-term contraception.26

LARC Insertion Timing

“Quick start” LARC insertion is recommended when feasible and clinically appropriate to minimize pregnancy risk from unprotected intercourse.27 LARC can be inserted same-day if the last menstrual period was within seven days, or with a negative urine pregnancy test and no unprotected intercourse since the last menses. Cu-IUDs or 52 mg LNG-IUDs can be inserted even after this seven-day window without waiting for menses if the pregnancy test is negative and unprotected intercourse occurred only within the past five days.27 While not FDA-approved for emergency contraception, Cu-IUDs are the most effective emergency contraceptive when inserted within five days of intercourse.28 Recent research suggests the 52 mg LNG-IUD may have comparable emergency contraception efficacy within the same timeframe.29

Assessing Safety and Medical Appropriateness

Determining LARC safety for patients with specific medical conditions is crucial. The US CDC’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use provides recommendations based on medical conditions and comorbidities.30 For most conditions affecting adolescents, LARC initiation and continuation are category 1 (no restriction) or 2 (advantages outweigh risks). Notable exceptions include current or recent breast cancer (prohibits progestin-containing LARC, category 4) and systemic lupus with antiphospholipid antibodies or liver tumors (LARC use permitted, but category 3, risks outweigh benefits).30 While these scenarios are uncommon in adolescents, understanding LARC safety guidance for specific medical conditions is vital for reassuring adolescents and families.

Epidemiology of Adolescent LARC Use: US Epidemiology

Adolescent LARC use in the US has increased significantly, contributing to a record low adolescent birth rate of 15.4 births per 1000 adolescents aged 15–19 in 2020.3,31 However, unmet contraceptive needs and disparities persist. Over 22% of females who began intercourse before 20 did not use any contraception (including condoms) at first intercourse, highlighting the need for early contraception education.4 While US adolescent LARC use is rising, data vary on the exact extent. The National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) found LARC use at last intercourse among never-married adolescents aged 15–19 increased from 3% (2006–2010) to 15% (2015–2019).32 Specifically, 5% used IUDs and 10% used implants.32 20% reported ever using LARC, suggesting about 25% of adolescent LARC initiators may seek removal.4 In comparison, 12.7–13.7% of US women aged 20–39 were current LARC users in 2017–2019.33 The National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS), a high-school student survey, observed a smaller increase in current IUD/implant use among adolescents aged 15–19, from 1.6% (2013) to 4.8% (2019).5 Discrepancies between datasets may stem from differences in sexual activity rates, question wording, or disclosure in survey vs. interview formats.34 Both sources, however, confirm substantial recent growth in adolescent LARC use.

Racial disparities in US adolescent LARC uptake persist, with higher usage among non-Hispanic White (6.7%) compared to non-Hispanic Black (2.0%) or Hispanic (1.6%) adolescents aged 15–19.5 This is particularly concerning given racial/ethnic pregnancy rate disparities, with non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adolescents experiencing rates over twice as high as non-Hispanic White adolescents.35 In contrast, overall LARC use among adult US women does not differ significantly across these racial/ethnic groups.33 Addressing complex, systemic factors underlying these disparities requires further effort.

Global Epidemiology

Adolescents in LMICs face significant obstacles to contraception access and use, impacting both uptake and continuation.36 Globally, 95% of the 16 million adolescent births (ages 15–19) annually occur in LMICs, leading to higher complication rates and health risks.36 Unmet contraceptive needs in LMICs range from 34–67% among unmarried adolescents aged 15–19 and 7–62% among married adolescents.36 Adolescent-specific LARC use data are limited in many regions, especially in countries where unmarried women are not asked about contraception.37 Among all women aged 15–49 worldwide, LARC use has increased in the past 25 years, with IUD users rising from 133 to 159 million (8.4% of women aged 15–49) and implant users from 2 to 23 million (1.2% of women aged 15–49).37 IUD use is lower among women in low-income (3.0%) and low-middle-income (3.6%) countries compared to upper-middle-income (16.3%) and high-income (6.5%) countries.37 Geographically, IUD use is highest in Eastern and South-Eastern Asia (18.6%) and lowest in Sub-Saharan Africa (0.7%) and Oceania (0.3%).37 Conversely, implant use is higher in low-income countries (3.7%) than other regions (0.6–1.2%).37 Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest implant use rates globally (4.5%), a substantial increase from 1.1% since 2011, driven by public health initiatives to improve implant affordability, access, and delivery in the region.37,38

LARC Uptake, Continuation, and Barriers to Use

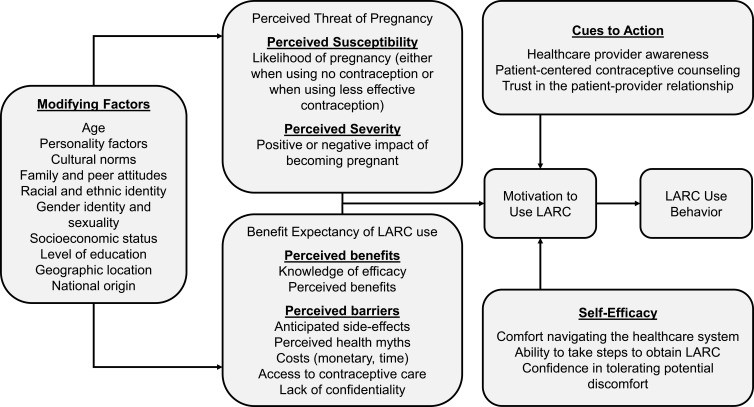

Many factors shape adolescent perceptions of LARC and their decisions to use it.39 The Health Belief Model (HBM) provides a framework for understanding health behavior, considering perceived threat (susceptibility and severity), benefits and barriers to action, and cues to action.40 Interventions to promote adolescent contraception often use HBM constructs to model decision-making and predict behaviors.41 Figure 1 applies HBM constructs to summarize factors affecting adolescent LARC use in the US, the primary focus of this review. LARC experiences and attitudes among adolescents globally deserve further, specific investigation.42–46

Figure 1.

Application of the Health Belief Model Constructs to LARC Use in Adolescents. [alt text: Health Belief Model applied to adolescent LARC use, showing perceived susceptibility, severity, benefits, barriers, cues to action, and self-efficacy influencing the likelihood of LARC adoption.]

Factors Affecting Adolescent LARC Uptake

Adolescent LARC decision-making is influenced by a delicate balance of contraception characteristics, acceptability, anticipated insertion discomfort, health myths, and shared cultural narratives.47 Factors affecting adolescent LARC uptake largely mirror those for adults, except romantic partners play a lesser role in adolescent contraception decisions.39

Acceptability

Adolescents often use less effective contraception than adult women, a discrepancy rooted in complex reasons, often centered on perceived device acceptability. Fewer adolescents have heard of IUDs (77.3%) and implants (78.6%) compared to oral contraceptive pills (97.2%) and Depo-Provera injections (82.1%).48 LARC acceptability is relatively similar for IUDs (37%) and implants (43%) among adolescents and young adults, but with polarized views – some highly interested, others highly disinterested.48 This suggests that low LARC awareness contributes to low overall acceptability, and awareness-building could significantly increase adolescent knowledge and interest. Conversely, a substantial proportion of adolescents find implants (24.4%) and IUDs (18.5%) entirely unacceptable, highlighting the need for individualized, adolescent-centered contraceptive counseling.48

Contraception Characteristics and Preferences

Efficacy is paramount for most adolescents choosing contraception. Belief in LARC efficacy and acceptance of method-specific factors like convenience and duration are linked to higher LARC uptake.49 However, other factors are important, including non-contraceptive benefits, anticipated side effects, and menstrual changes. Some prefer regular menses, others amenorrhea.47 All LARC methods typically cause irregular uterine bleeding initially, lasting weeks or months. Mirena is most likely to induce amenorrhea, while low-dose IUDs and Cu-IUDs are more likely to maintain monthly cycles. Nexplanon often leads to breakthrough bleeding for weeks or months, usually resolving within six months, but some adolescents experience prolonged bleeding. For some, LARC’s high efficacy may not outweigh the benefits of user-controlled contraception that meets other valued criteria, such as predictable, lighter, or suppressed menstruation.

Age can influence LARC device preference. In the Contraceptive CHOICE project (St. Louis, 2008-2013), over 70% of adolescents initiated LARC.50 This project used “LARC-first” counseling, same-day insertion, and no patient cost-sharing. Among LARC adopters, adolescents aged 14–17 favored subdermal implants (63%), while 18–19-year-olds preferred hormonal IUDs (71%).51 Perceived invasiveness of pelvic exams and anticipated discomfort may explain younger adolescents’ preference for implants over IUDs.

Anticipation of Discomfort with Insertion

LARC insertion causes some discomfort or pain for most patients.52 Anxiety, pain fear, and procedural concerns are common, even among adolescents choosing LARC.52 Implant insertion typically involves minimal discomfort – a brief sting from local anesthetic injection. The remaining procedure feels like dull pressure and is usually under a minute. Healing may involve a mild bruise for several days.

IUD insertion, however, requires approximately five minutes of discomfort for speculum insertion, tenaculum application to the cervix, uterine depth sounding, and IUD insertion.52 Complex anatomy or cervical stenosis can prolong the procedure. While timing insertion during menses (when the cervix is naturally dilated) is sometimes attempted, research doesn’t support improved outcomes.53 Nulliparity is not a risk factor for failed IUD insertion.54 Patient experiences of discomfort/pain vary widely, from minimal to severe.55 Predictors of severe IUD insertion pain are limited, but dysmenorrhea history, nulliparity/low parity, and high anticipated pain may be indicators.52,56 Research on pain reduction interventions for IUD insertion has not yet found an optimal evidence-based analgesia approach.57 Despite this, fear of significant discomfort/pain is real and often amplified on social media, fueling adolescent anxiety, even though most adolescents report satisfaction after LARC insertion.58

LARC Health Myths

Misconceptions and fears often deter adolescents from LARC.47 Adolescents and parents often have significant concerns about LARC’s health effects, safety, and efficacy.48 Common myths include fears of infertility, cancer, ectopic pregnancy, and pelvic organ damage.9 Despite low failure rates, internet-based LARC information is often of variable quality, potentially contributing to knowledge gaps and inaccurate risk perceptions.59 Hormonal side-effect concerns persist for implants and hormonal IUDs, despite lower systemic hormone absorption from IUDs compared to other progestin-only methods.47 Table 1 outlines communication approaches to address these myths, including guidance on LARC misconceptions and accessibility barriers.

Table 1.

How to Address LARC Myths and Barriers with Adolescents and Rationale for Response

| LARC Myth | How to Address Myth | Rationale for Response |

|---|---|---|

| LARC methods can decrease my ability to get pregnant in the future (or reduce my future fertility). | The ability of the implant and IUD to prevent pregnancy is reversed as soon as the device is removed. There is no long-term reduction in your ability to get pregnant. | Many adolescents are concerned about returning to fertility after discontinuing a contraceptive method. The depot medroxyprogesterone acetate injection (Depo-Provera) is the only method associated with some delay in return to fertility; even this effect is not universal. |

| It is unsafe to skip or have no period, and I am worried that if LARC stops my periods, it could cause problems. | LARC methods stop the uterus lining from building up, so your period can be lighter or may stop altogether because there may not be much uterine lining to shed each month. | Setting expectations regarding changes to the menstrual cycle before initiating a LARC method will improve satisfaction and continuation. This is especially important for those whose goals include improving menstrual bleeding and decreased cramping. |

| LARC stops pregnancies by causing abortions. | Implantation of a fertilized egg is the definition of pregnancy. LARC prevents pregnancy before fertilization occurs, so no abortion is involved. | Implants and IUDs do not function by terminating pregnancies. Instead, they work to prevent ovulation (implant) or fertilization (IUD). |

| Having a device inserted increases my risk of infection (such as getting an STI or infection at the insertion site) | Increased infection risk is only present around the time of placement. Afterward, your chance of any infection is the same as anyone else. | While using a LARC does not make adolescents more likely to get an STI, providers should counsel that LARC does not prevent them from getting an STI either. |

| After the LARC device is placed, I cannot get it removed until a certain number of months or years have passed. | All LARCs can be removed at any time and do not have to stay in place for the entire duration of efficacy. The ability to get pregnant returns almost as soon as you get the device removed. | Adolescents have the right to refuse or discontinue a LARC method at any time. An adolescent-centered approach to counseling should include options for managing side effects and removal. |

| LARC methods are too expensive for me to afford. | Your health insurance should usually cover all contraceptive options at no cost. | Under the Affordable Care Act, insurance providers are required to cover all FDA-approved contraceptives, including LARCs. In certain states, state funds cannot be used to provide minors with confidential contraceptive services. |

| I need my parents’ permission and consent to get a LARC method. | In many states in the US, you can legally get a LARC without your parents’ consent or permission. | In many states in the US, adolescents can legally obtain contraception without parental consent or notification. Information regarding laws and restrictions in specific states is available at: www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_MACS.pdf |

Family, Cultural, and Shared Interpersonal Experiences

Interpersonal, cultural, and historical factors influence how individuals and communities value LARC characteristics and assess LARC acceptability and desirability.47,60 Social context and shared experiences of friends and family significantly impact LARC choices, positively or negatively.47,61 Misperceptions persist among adolescents and parents, such as the belief that nulliparous women cannot use IUDs or that insertion must occur during menstruation.9 Maternal acceptance of short-acting contraception is generally higher than LARC.62 Negative stories from family and friends, important sources of medical information for adolescents, can dissuade LARC use. Adolescents less interested in LARC often have a friend or family member with a negative LARC experience.48

Communities with histories of reproductive coercion may have specific LARC concerns.10 Qualitative research shows that historical reproductive injustice shapes patient concerns about being steered towards LARC based on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and education.63 Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black women reported feeling pressured to choose and continue LARC, with some providers resisting removal requests.63 Awareness of potential coercion and reproductive autonomy concerns is vital for adolescent-centered contraceptive care. Adolescent health care communication programs, especially those using creative mediums like teen theater, can address these sensitive issues by fostering open dialogues about reproductive justice and historical contexts within communities.

Factors Affecting Adolescent LARC Continuation and Discontinuation

LARC continuation and discontinuation rates are influenced by various factors, including specific populations, medical comorbidities, side effects leading to early removal, and IUD expulsion.

Continuation and Discontinuation Rates

While adolescent LARC continuation is higher than non-LARC methods, adolescents may discontinue LARC more often than adult women. In the CHOICE project, adolescent continuation rates for copper IUDs (75.6%), LNG-IUDs (80.6%), and implants (82.2%) were lower than for women over 26 (84–86% for each LARC method).64 However, adolescents are significantly more likely to continue LARC than short-acting contraception. 12-month LARC continuation rates for adolescents (86.4% for IUDs, 85.3% for implants) are much higher than the 39.8% continuation rate for oral contraception, the most common short-acting method.65 Adolescents are also more likely to discontinue short-term methods compared to adults, as seen in lower 12-month oral contraceptive continuation rates among adolescents vs. adults 26+ (44% vs. 53%).64 Most adolescents report high LARC satisfaction and intention to continue LARC after one year.[64](#cit0064] However, adolescent satisfaction may be lower than adults. In the CHOICE project, 75% of adolescents aged 14–19 were very satisfied with LARC, compared to 83% of adults 26 and older.64

Postpartum and Postabortion LARC Placement

Postpartum LARC placement reduces repeat pregnancy and is recommended by ACOG.1 Adolescents receiving postpartum LNG-IUDs reported 100% satisfaction at 12 months and had much higher 12-month continuation rates (77%) than postpartum adolescents receiving Depo-Provera (43%).66 While postpartum IUD insertion has a slightly higher expulsion rate (10.2% for immediate post-placental placement, 13.2% within 72 hours), it effectively addresses the unmet needs of the 40–70% of postpartum women who initially intend to get an IUD but don’t.67,68 Postpartum implant placement also leads to higher initiation rates compared to delayed insertion.69 Adolescents receiving postpartum implants have higher initiation rates than those receiving placement at 6 weeks and are more likely to have the device in place at 3 months.70

Immediate post-abortion LARC provision is safe and effective for adolescents after medical or surgical abortion, reducing the high risk of repeat pregnancy in this group.1 Immediate postabortion LARC is generally acceptable to adolescents and nulliparous women, though uptake may be lower than in parous and adult women.71,72 Importantly, immediate LARC initiation does not increase medication abortion failure risk.73 IUD complication and expulsion rates following first-trimester uterine aspiration and medication abortion are low.74 Immediate postabortion IUD insertion leads to higher initiation rates (96%) than interval insertion (23%), primarily due to failure to return for follow-up.75

Disadvantages and Reasons for Early Removal

While few adolescents opt for early IUD removal, several factors contribute. A systematic review of IUD continuation in adolescents and young adults (<25) found bleeding and pain were the most reported side effects.65 However, these rarely caused device removal. Unpredictable post-IUD bleeding was generally acceptable to most adolescent IUD users.65,66 Most post-IUD insertion pain occurred shortly after insertion and responded to oral analgesics. IUD-related pain leading to removal mainly occurred within the first three months post-insertion.65

Bothersome “nuisance” bleeding is the most common reason for subdermal implant discontinuation.76 Proactive anticipatory guidance about potential side effects is crucial for setting realistic post-insertion expectations. Users should be informed that post-insertion abnormal uterine bleeding is normal and not a sign of harm. Offering short-term medication, like oral contraceptives, may reduce bleeding and prevent discontinuation for those willing to try it.76

Medical Indications to Discontinue LARC

Most common LARC side effects, like irregular bleeding or cramping, do not necessitate removal unless requested by the patient. However, the emergence of conditions contraindicating progestin-containing LARC, as discussed earlier, would typically prompt removal.30 Otherwise, continuing pre-existing LARC is generally acceptable in most medical situations, including some where initiation is not recommended, such as active pelvic inflammatory disease, cervical or endometrial cancer, or complicated solid organ transplantation.30 Counseling on risks and benefits of LARC continuation in comorbid medical conditions should be adolescent-centered and involve shared decision-making.

IUD Expulsion in Adolescents

Spontaneous IUD expulsion occurs in a small percentage of recipients, estimated at 2–10% in adult women.1 Risk factors for adolescents and adults include heavy menstrual bleeding, higher BMI, and postpartum insertion.77 Most adolescents, but not all, recognize IUD expulsion.65 While not a contraindication to future IUD use, adolescents should be informed it’s a risk factor for repeat expulsion. The subsequent IUD expulsion rate in adolescents with a history of expulsion is nearly 30%, similar to adults.1,78

While younger age may be a risk factor for IUD expulsion, rates in adolescents are not definitively higher than in adults.77 Studies in adolescents show expulsion rates ranging from 1% to about 15%.65 In the CHOICE project, adolescents aged 14–19 experienced expulsion rates of 10.5% at 12 months and 18.8% at 36 months, roughly twice as high as rates for women over 20 (5.7% and 9.3%, respectively). Importantly, neither nulliparity nor IUD type was a risk factor in this study.77 Systematic reviews show pooled IUD expulsion rates of 8.0% (95% CI 4.0–11.0%), but studies exhibit significant heterogeneity.79

Barriers to Adolescent LARC Use

Despite recent increases, adolescent LARC use still lags behind short-term contraception. Barriers to adolescent LARC use are multifaceted, encompassing healthcare provider misconceptions, legal, administrative, and practical constraints, and patient concerns about cost, access, and confidentiality. Successful system-level interventions have addressed multilevel adolescent LARC barriers. Understanding these hurdles is crucial for improving provider counseling and healthcare systems.

Healthcare Provider Knowledge Gaps

Healthcare providers can be a barrier to adolescent LARC use due to lack of knowledge, comfort, or LARC provision training.6 Inadequate LARC education exists in medical school, residency, and independent practice.80,81 Myths and misconceptions held by some providers can unintentionally or intentionally dissuade adolescents from LARC.60 Historically, before recent AAP and ACOG recommendations, many providers viewed IUDs as unsuitable for nulliparous adolescents.2,82

Some providers may not counsel adolescents about or offer LARC options at all.1,19 Limited provider LARC counseling may contribute to low LARC awareness among adolescents, given that nearly three-quarters view providers as their primary LARC information source.83 Adolescent health care communication programs can play a vital role in bridging these knowledge gaps by educating healthcare providers and disseminating accurate information about LARC safety and efficacy for adolescents.

Legal, Administrative, and Practical Constraints

While practical and economic difficulties affect all patients, adolescents are particularly vulnerable and require extra support to overcome logistical barriers to LARC access. Many states or institutions require parental consent for outpatient procedures, overriding adolescents’ urgent need for LARC access.84 Adolescents may be unaware of resources like Title X-funded clinics offering free and confidential care in most US states.85 Independent service access can be further limited by transportation needs, clinic proximity, or lack of privacy. Clinic scheduling constraints or device ordering needs often require separate procedure appointments, leading nearly half of adult women to miss IUD insertion appointments.86 Teen theater and other creative communication methods can effectively raise awareness among adolescents about their rights to confidential care and available resources.

Cost and Access

Cost is a significant barrier to LARC for both providers and patients. While US health insurance must cover 100% of LARC device and insertion costs under the Affordable Care Act, commercially insured patients often have out-of-pocket expenses.87 Uninsured youth, unable to access or unaware of free/low-cost family planning services, may be deterred by LARC costs.6,88 Cost is also a factor for providers, including upfront device purchase costs, procedural equipment, longer appointments, and device expiration/non-reimbursement risk. Insufficient device stocking in clinics limits same-day insertion services for adolescents desiring LARC.86 Removing these barriers will enable evidence-based same-day LARC insertion for adolescents who choose it.6,80 Adolescent health care communication programs can advocate for policies that ensure equitable access to affordable LARC for all adolescents, regardless of their insurance status or socioeconomic background.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality is crucial in adolescent contraceptive care. Most US states allow minors to consent to contraception.85 Title X and Medicaid funding offer federal protections for confidential minor contraception access.85 However, state regulations may conflict or lack guidance on confidential adolescent contraception access.85 Adolescents may fear unintended disclosure of contraceptive services to parents via insurance explanations, electronic health record releases, or telehealth settings where parents might overhear.89 Guidance on maintaining billing confidentiality is available from the AAP and Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine.90 Teen theater performances and workshops can create safe spaces for adolescents to learn about their confidentiality rights and address their concerns in an engaging and relatable way.

Multilevel Interventions to Address Adolescent LARC Barriers

Research on evidence-based interventions to improve LARC access and uptake is ongoing.91 Notable multilevel interventions have addressed LARC barriers for adolescents and adults. The CHOICE project, using “LARC-first” counseling and systemic interventions, resulted in 72% LARC uptake among adolescents, significantly exceeding national rates (5–15%).5,32,51,92 This reduced adolescent birth rates (ages 15–19) to 19.4 per 1000 and abortion rates to 9.7 per 1000 (compared to 94.0 and 41.5 per 1000, respectively, in sexually experienced US adolescents in 2008).92 The Colorado Family Planning Initiative similarly addressed multilevel barriers to adolescent LARC uptake. Following implementation, IUD use among ages 15–19 rose from 1.6% (2008) to 9.8% (2019), and hormonal implant use from 0.9% (2008) to 23.1% (2019).93 This coincided with birth rate reductions from 39.6 to 13.5 per 1000 and abortion rate reductions from 11.2 to 3.9 per 1000 among adolescents aged 15–19.93 Dozens of other local and state initiatives are ongoing, many funded by the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Program (Office of Population Affairs, 2010).94 Adolescent health care communication programs can learn from these successful multilevel interventions and adapt strategies to address local barriers and needs.

Practices to Support Better Communication, Counseling to Empower Uptake, Continuation, and Adherence

Effective contraceptive counseling that promotes parent-youth communication and addresses discontinuation proactively can enhance adolescent LARC uptake, continuation, and adherence. Key communication goals include building adolescent-provider relationships, trust, and shared decision-making.95 Shifting from presumptive counseling to an adolescent-centered, shared decision-making approach, while encouraging parent-adolescent sexual health communication, allows providers to view contraceptive counseling through a reproductive justice framework. Table 2 outlines key communication strategies, including clinical guidance on avoiding pitfalls and effectively addressing factors impacting LARC decisions sensitively.96 Teen theater can be an innovative tool within these communication strategies to engage adolescents and families in discussions about sensitive topics and promote open communication.

Table 2.

Communication Strategies When Considering LARC Placement with Adolescents

| Areas of Focus | Consider Saying: | Avoid Saying: | Why This Matters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Introduction of contraceptive options | Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) methods are the most reliable and effective methods for preventing pregnancy. | The best options for you are LARC methods. I recommend LARC methods above all others for all my adolescent patients. | Comprehensive contraceptive options should be discussed, and providers should avoid being coercive or overly directive. Providers should not assume LARCs are the best options for all their patients. |

| Adolescent-centered counseling | What is most important to you? (How well it prevents pregnancy, or something else?) How do you value other aspects such as ease of use, avoiding discomfort, side effects, or how long a method works? | We do not need to discuss other contraceptive options in detail or seriously consider them because LARCs are the most reliable and effective. | While LARCs offer the highest efficacy and reliability, providers should respect patients’ autonomy regarding selecting a contraceptive method based on whatever characteristics are most important to them. |

| Supporting autonomy | Contraception is a personal decision. The best choice will differ from person to person and at different stages in one’s life. All LARC methods can be stopped when you do not want them anymore. | A LARC method is meant to be kept in for the entire effective duration. You should not get a LARC method if you do not plan to keep it in place for the intended time. | Adolescents may be discouraged by the idea of committing to a method for a long duration. Counseling that a LARC can be discontinued at any time during use may enhance acceptability and willingness to initiate a LARC. |

| Anticipation of discomfort with LARC placement | Getting a LARC placed can be uncomfortable. At the same time, each person can have a different placement experience. Providers who place LARC have special training on how to place it and can offer you medications and other comfort measures before and after placement to make it easier for you. | Getting your LARC placed will not be painful. Even if some pain is involved, you should remember that any discomfort is worth the years of not having to think about your birth control. | Most women will experience discomfort with LARC placement. Providers should acknowledge this and recommend methods to help minimize it. Underrepresenting the potential for pain is dismissive of the patient’s concerns and the range of possible experiences. |

Presumptive Counseling and the Potential for Coercion and Bias

Many interventions to increase adolescent LARC uptake have used directive “LARC-first” counseling, prioritizing discussion of the most effective methods (LARC) first, assuming patients desire maximum efficacy.92,97 The Contraceptive CHOICE project used “LARC-first” counseling with no-cost, same-day services, achieving 72% adolescent LARC uptake and drastically reducing pregnancy rates.50,92

While effective, “LARC-first” counseling risks coercion if adolescent autonomy and alternative contraceptive priorities are not centered.27,98 Racial bias can also influence provider recommendations, with providers being more likely to recommend LARC to low-income Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black women than low-income White women.99 Balancing patient attention and prioritization with the risk of unintentional reproductive coercion due to differential LARC recommendations across demographics is crucial. Adolescent health care communication programs must be mindful of these potential biases and ensure equitable and unbiased counseling for all adolescents.

Adolescent-Centered, Shared Decision-Making Approach

Patient-centered, and specifically adolescent-centered, approaches avoid potential coercion associated with directive or presumptive counseling. Providers often combine relational communication (building understanding and trust) with task-oriented communication (providing practical solutions).95

Shared decision-making utilizes the best scientific evidence alongside patient values and preferences to determine the best contraception method for each individual.47,95 This balance involves avoiding provider imposition of their preferred method due to efficacy. Instead, shared decision-making provides evidence within the context of individual and family preferences, prioritizing adolescent autonomy and informed choice.95,100 Adolescent-centered, shared decision-making contraceptive counseling should provide unbiased care, acknowledging historical systemic injustice, discrimination, and racial disparities in reproductive healthcare.101 Teen theater can be a powerful tool to facilitate shared decision-making by presenting scenarios and narratives that explore different contraceptive choices and their implications, allowing adolescents to reflect on their own values and preferences.

Encouraging Parent-Adolescent Sexual Health Communication

Empowering providers to encourage parent-adolescent contraception conversations at home is a crucial first step to improve sexual health communication. Parental knowledge, attitudes, beliefs about LARC, and motivations and concerns about adolescent contraception are key counseling targets. Parent views on LARC significantly influence adolescent acceptability and desirability.102 Parent-youth sexual and reproductive health conversations effectively promote safer adolescent sexual practices.103 Cultural concerns that discussing contraception might encourage adolescent sexual activity often lead parents to avoid these discussions, potentially causing providers to also avoid the topic due to anticipated resistance.104,105

Advance timing is essential. Providers should proactively counsel adolescents and families about contraception, including LARC, before sexual activity begins.106 With increasingly restrictive US reproductive healthcare laws following the overturning of Roe v. Wade, contraception communication and counseling are even more critical for primary pregnancy prevention.107 Given potential threats to confidential contraception access in many US regions, providers should view each communication opportunity with preteen and adolescent patients as a key moment to discuss essential reproductive healthcare services access.108 Teen theater can serve as a catalyst for initiating these crucial parent-adolescent conversations, creating a platform for families to engage with sensitive topics in a non-threatening and informative environment.

Using a Reproductive Justice Framework

Empowering adolescent reproductive autonomy should underpin all effective reproductive communication strategies. Reproductive health service providers must consider the impact of reproductive health advancements on structurally disadvantaged populations. Integrating a reproductive justice approach into a “LARC promotion toolkit” is essential for all LARC conversations with families and patients.8 First, LARC should not be presented as the sole “solution” to unintended pregnancy. Incorrectly portraying LARC as a magic bullet to “solve” societal issues like adolescent pregnancy-related poverty is misleading. Without addressing cultural and structural factors contributing to adolescent pregnancies, LARC alone cannot diminish reproductive healthcare access inequities.8,109

Second, a reproductive justice framework emphasizes bodily autonomy, affirming every woman’s right, including adolescents, to choose the best method for herself, rejecting directive “first-line” paradigms that prioritize LARC over all else.110 Providers should value all methods, even less effective ones, to align with individual desires, adhering to a reproductive justice framework that opposes directing patients toward specific contraceptive methods.

Lastly, a reproductive justice framework recognizes the historical failure to acknowledge injustices faced by poor women of color. The Sister Song Women of Color Reproductive Justice Collective and the National Women’s Health Network suggest healthcare providers directly address reproductive injustice concerns and acknowledge racist and eugenicist legacies that might explain why poor women of color may feel socio-demographically targeted by LARC recommendations.111 A reproductive justice framework aims to enable adolescent LARC access and use if desired, and removal when desired, while directly acknowledging past reproductive abuses against socially disadvantaged groups.111 The ultimate goal is to enhance health, social well-being, bodily autonomy, and integrity for all individuals, especially marginalized women historically oppressed, and to ensure individuals feel safe making the best reproductive decisions without provider pressure, coercion, or judgment. Teen theater can be a powerful medium to explore these complex issues of reproductive justice, historical injustices, and systemic disparities, fostering critical reflection and promoting empathy and understanding within communities. By incorporating these themes into theatrical performances and workshops, adolescent health care communication programs can empower young people to become advocates for reproductive justice and health equity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LARC is a vital tool for adolescents seeking pregnancy prevention. Addressing barriers like myths and access hurdles can help providers facilitate LARC uptake, continuation, and adherence. Adolescent-centered, shared decision-making communication strategies within a reproductive justice and health belief model framework can increase LARC awareness and empower uptake while respecting adolescent autonomy and incorporating family values in contraceptive choice. Furthermore, innovative approaches such as integrating teen theater into adolescent health care communication programs offer promising avenues to enhance communication, engagement, and understanding around adolescent reproductive health, ultimately empowering teens to make informed choices about their health and futures.

Abbreviations

LARC, Long-Acting Reversible Contraception; DMPA, Depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (Depo-Provera); IUD, Intrauterine device; Cu-IUD, Copper IUD; LNG-IUD, Levonorgestrel IUD; STI, Sexually Transmitted Infection; US, United States.

Disclosure

This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (K23 HD097291) and the UT FOCUS award from the American Heart Association, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and the Harry S. Moss Heart Trust. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the study sponsors. The sponsors did not have a role in the review design, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication. Dr Melanie A Gold reports grants from Merck/Organon, consulting fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. Dr Jenny KR Francis reports grants from the National Institutes of Health (K23 HD097291), grants from the UT FOCUS award funded by the American Heart Association, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and the Harry S. Moss Heart Trust, and grants from an Organon Investigator-Initiated Study during the conduct of the study. The authors have no other relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.