Introduction

As populations worldwide age, the demand for robust and effective aged care systems becomes increasingly critical. Australia, like many developed nations, faces the challenge of supporting a growing elderly demographic. Projections indicate a significant rise in the proportion of Australians aged 65 and over, escalating from under 15% to an estimated 21% by mid-century [1]. In 2015, approximately 176,967 Australians resided in residential aged care, with the vast majority being over 65 [2]. While this represents a relatively small percentage of the total over-65 population at any given time, lifetime usage rates are considerably higher [3]. This context underscores the importance of initiatives like the Aged Care Assessment Program (ACAP) and the guidelines that shape its operation, particularly the Aged Care Assessment Program Guidelines 2015, which were crucial in navigating these demographic shifts.

Australia’s aged care policy strongly emphasizes “ageing in place,” aiming to support older individuals in maintaining independence within their communities. This principle was reinforced by the Aged Care (Living Longer Living Better) Bill 2013, which prioritized community care services. Despite this focus, the sheer number of older Australians needing residential care is projected to increase substantially due to overall population ageing [4]. Understanding the mechanisms that govern the transition into residential care is therefore paramount for effective planning and resource allocation.

The Aged Care Assessment Program (ACAP), operating under the Aged Care Act 1997, plays a central role in this process. Aged Care Assessment Teams (ACATs) are responsible for evaluating individuals and recommending appropriate long-term care settings (RLTCs). These recommendations, guided by frameworks like the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015, can range from remaining in a private residence or independent living to residential care, hospital settings, or other forms of institutional care. It’s important to note that ACAP recommendations are distinct from the actual approval for residential care, which is influenced by factors such as service availability and individual financial assessments. However, the ACAP assessment is a mandatory initial step for accessing residential care and various support services, including home care packages, respite care, and flexible care options. These services are designed to support individuals in non-residential settings such as their homes or independent living facilities.

For government bodies at both the federal and state levels, a clear understanding of the pathways through the aged care system is essential for strategic planning and financial management. While previous research has explored aged care service utilization preceding death and the impact of disease on care entry [5–6], and descriptive analyses from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) have provided overviews of hospital-residential care transitions and demographic service usage [6–10], in-depth multivariate studies on aged care assessments and recommendations have been less common. Significant contributions in this area include recent studies examining factors associated with entry into residential care [11–12].

Studies by Kendig et al. [11–12] and Wang et al. [13] in Australia, along with international research [14–20], confirm a strong link between functional, mental, and physical health conditions and the likelihood of entering and residing in residential aged care. Assistance needs, alongside age, are consistently identified as primary determinants of residential care entry [18,21], echoing earlier findings highlighting age, functional status, and mental status as key predictors of nursing home admission [22–24].

However, a critical knowledge gap persists regarding the detailed recommendations made during ACAP assessments in Australia. Specifically, there has been limited quantitative research into how ACATs differentiate care setting recommendations for older Australians, whether for community-based or institutional care. This article addresses this gap by exploring several key questions: First, what is the distribution of recommended long-term care settings (RLTCs) determined by ACATs in Australia, such as private residence versus residential care? Second, how do these recommendations vary based on clients’ demographic and health characteristics? Finally, how significantly do assistance needs (like self-care assistance) and the availability of carers influence ACAT recommendations, operating within the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 framework?

The Aged Care Assessment Program: Context and Guidelines

The approach to aged care systems varies significantly across OECD countries. Australia stands out for its nationally standardized assessment tool used during ACAP assessments, which dictates access to government-funded services both inside and outside of community settings. Australia’s system blends elements of liberal models (similar to the UK, focusing on tax-funded, means-tested, service-oriented support) with socio-democratic principles of universal support [25]. Like many nations, excluding the USA, Australia provides a universal safety net for residential care needs [26]. Residential care facilities receive government support for residents assessed as being below a ‘minimum permissible asset value,’ although these facilities are not obligated to accept all applicants due to capacity or service limitations [27].

The primary goal of the ACAP is to evaluate care needs and facilitate access to appropriate care for frail older individuals, thereby enhancing their health and overall well-being [28]. An ACAP assessment is initiated when ACATs receive requests or referrals for assessment from various sources. An ACAT recommendation is a prerequisite for accessing Commonwealth-subsidized aged care services, including residential aged care, home care, or transition care. While the ACAT recommendation is the essential first step in obtaining these services, it does not guarantee placement in a care facility. The aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 provided the framework for these crucial decisions during the study period.

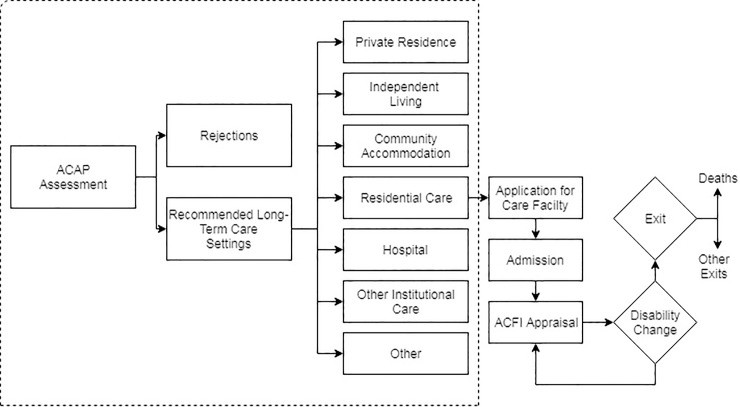

The Aged Care Act 1997 mandates that ACAP assessments be conducted by registered ACATs, who then make recommendations regarding the most suitable living and care arrangements for the client, termed the long-term care setting recommendation [29]. Figure 1 illustrates the idealized pathway for individuals post-ACAP assessment. Following an assessment, an individual’s ACAP can be approved for care in a recommended long-term care setting (RLTC) or not approved. Approval is contingent upon meeting eligibility criteria outlined in division 21 of the Act and Part 2 of the Approval of Care Recipient Principles 2014. Assessments resulting in a determination that an individual does not meet eligibility for any care program under the Act are categorized as “No Care Approved.”

Fig 1. Individuals idealised pathway to care in Australia.

Note: Our analysis pertains to the ACAP assessment in the highlighted box.

Not all assessments lead to approval for permanent residential care, necessitating consideration of alternative RLTC settings. These include private residences, independent living, community accommodation, residential care, hospitals, other institutional care, or other arrangements. Services provided within these settings can encompass home care, respite care, transition care, or short-term restorative care, all operating within the principles of the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

For individuals recommended for residential care, approval precedes applications to specific facilities and subsequent admission. This pathway is further complicated by factors like the availability of places in the desired location, means testing, and government budgetary constraints on supply. Even after ACATs recommend aged care packages (residential or home and community), waiting periods before commencement are common, and some individuals may not proceed with an aged care program at all. Service availability in specific regions, limited by government license allocations, is a contributing factor. Some areas experience oversupply, while others face excess demand for various services [30]. Both service providers and consumers have voiced concerns regarding allocative efficiency within this pathway [31–32].

Upon admission to residential care, an Aged Care Funding Instrument (ACFI) appraisal is conducted to assess the client’s assistance and care needs across three domains: daily living, behavioral needs, and complex health care (Figure 1). The ACFI appraisal is regularly updated to reflect changes in client needs, and government subsidies to the facility are adjusted accordingly.

This study concentrates specifically on the assessor’s recommendation stage within the ACAP process (highlighted in Figure 1), which is directly informed by documents such as the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015. The definitions of the RLTC settings are detailed in Table 1 [33].

Table 1. The definitions of the recommended long-term care settings.

| RLTCs | Description |

|---|---|

| Private Residence | Houses, flats, units, caravans, mobile homes, boats and marinas |

| Independent living within a retirement village | Living in self-care independent living units, regardless of whether it is owned or rented. Where provision of care is provided in this setting, it is coded as ‘supported community accommodation’ |

| Supported community accommodation | Living settings or facilities in which support or care is provided by staff or volunteers. Examples include domestic scale-living facilities (e.g., group homes for people with disabilities, congregate care apartments), large scale supported care facilities |

| Residential care | Residential aged care services, multipurpose services and multipurpose centres |

| Hospital | Long-term care in a hospital setting |

| Other institutional care | Other institutional settings providing care (e.g. Hospices, long stay psychiatric institutions) |

| Other | All other types of community settings |

The decision regarding RLTC settings is holistic, considering the client’s physical, psychological, medical, cultural, social, and restorative care needs. ACATs also assess the client’s typical living situation, financial circumstances, need for assistance, and access to transport and community support systems. The needs of carers and the client’s personal preferences are also taken into account, aligning with the person-centered approach advocated by the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

As part of the initial assessment and needs identification, the ACAP toolkit provides assessors with validated, nationally consistent tools. From late 2015, assessors began utilizing the My Aged Care online portal, employing the National Screening and Assessment Form. Following the initial assessment, ACATs develop a care plan detailing the client’s service needs. ACATs then engage in ‘care coordination to the point of effective referral’ [28], which involves supporting the client and their support network in implementing the care plan and accessing necessary services. The aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 significantly influenced the implementation and standardization of these processes during this period.

Data and Methods

Data

This study utilized unit record administrative data from the National Aged Care Data Clearing House (NACDCH) [34], encompassing over 800,000 aged care assessments. The ACAP data are derived from ACAT assessments, with over 150,000 assessments completed annually. The NACDC receives the recommendations made by ACAT teams upon completion of each assessment. This dataset is crucial for understanding the practical application of guidelines such as the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

The confidentialized ACAP file included all ACAP referrals received by ACAT members between July 1, 2010, and June 30, 2013. Prior to analysis, 236,595 incomplete records were removed. A further 97,807 duplicate records, identified by identical approval and referral dates, were also excluded. Additionally, 2,101 records with missing assessment dates and 49 cases with unknown client gender were removed. Finally, 18,484 cases involving individuals under 65 years of age were excluded, as this study focused on the population typically addressed by aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 and related programs. After these exclusions, the final sample consisted of 492,628 ACAP assessments for individuals aged 65 years and over. The analysis was limited to this age group as they are not eligible for services through the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

To protect client confidentiality, not all variables from the ACAP assessment are accessible to researchers. A significant omission is geocoded records. Supply constraints are a critical factor in the allocation of both residential and home care services. Ideally, access to data at the Aged Care Planning Region level or lower would enable detailed analyses of the interplay between ACAPs, resource allocation, unmet demand, and regional supply variations. Nonetheless, the available data provided vital measures of individual characteristics and care needs, including age, carer availability, health conditions, sex, state of residence, and RLTC setting, all of which are considered within the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 framework.

Approval to use data

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) provided the data to the authors as part of ongoing efforts to improve access to aged care data for research purposes. The Australian Federal Government collected the data under the Aged Care Act, and a de-identified dataset is available to registered users for research.

Measurement

Several measures of ACAP clients’ health were available within the dataset. Clients’ health conditions were categorized into 18 groups using the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) framework [35]. In addition to analyzing RLTC settings by ICD type, the study also examined differences based on counts of health condition types as a measure of comorbidity. These health measures are key components considered in the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 for determining appropriate care settings.

Beyond detailed health measures, the confidentialized dataset included measures of Activities of Daily Living (ADL). These variables provide crucial insights into the functional status of older Australians, specifically their need for assistance with communication, mobility, walking, self-care, transport, meals, domestic tasks, social activities, and health management (Table 2) [33]. ADL assessments are central to the evaluation process guided by the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

Table 2. ADL assistance needs definition.

| ADL | ADL Description |

|---|---|

| Needing the assistance or supervision of another person with: | |

| Move | Activities such as maintaining or changing body position, carrying, moving and manipulation |

| objects, getting in or out of bed or a chair | |

| Moving | Walking and related activities, either away from home or away from home |

| Communication | Understanding others, making oneself understood by others |

| Health | Taking medication or administering injections, dressing wounds, using medical machinery, |

| manipulating muscles or limbs, taking care of feet (includes a need for home nursing and allied | |

| health care, such as physiotherapy and podiatry) | |

| Self Care | Daily self-care tasks such as eating, showering/bathing, dressing, toileting and managing |

| incontinence | |

| Transport | Using public transport, getting to and from places away from home or driving |

| Social | Shopping, banking, participating in recreational, cultural or religious activities, attending |

| day centres, managing finances and writing letters | |

| Domestic | Household chores such as washing, ironing, cleaning and formal linen services |

| Meals | Meals, including the delivery of prepared meals, help with meal preparation and managing |

| basic nutrition | |

| Home | Home maintenance and gardening |

| Other | Needs assistance with other tasks not stated above |

The client’s usual accommodation setting, as recorded by the ACAT assessor, was also measured. If the ACAP assessment occurred outside of the usual accommodation setting and was temporary, the assessor recorded the usual setting, not the assessment location. For instance, if an individual typically residing in a private residence was assessed while temporarily hospitalized, their usual accommodation setting was coded as private residence. This is important context for understanding the baseline from which care recommendations are made within the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

Statistical model

To analyze the relationship between demographic characteristics, assistance needs, health conditions, and recommended long-term care settings, Stata 14.0 software [36] was used. Given that the dependent variable, RLTC, is polytomous (with 6 categories), a multinomial logistic regression model (MNL) was specified. Relative Risk Ratios (RRR) were generated from the raw MNL coefficients to quantify the change in the odds of a particular RLTC setting given a one-unit change in each demographic, health, and assistance needs measure. A private residence RLTC setting served as the base group for the MNL specification, making the RRR interpretation analogous to odds ratios in standard logistic regression. This approach allows for examining how different factors, as outlined in documents such as the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015, influence the type of care setting recommended.

Model stability was assessed by splitting the sample into RLTC pair groups (e.g., private residence vs. independent living, private residence vs. residential care) and estimating standard logistic regression models. These coefficients were then compared with those from skewed logistic regression and penalized maximum likelihood estimation [37–38]. The models showed strong consistency in the direction and significance of coefficients, and the MNL model was chosen for simplicity in presentation.

To evaluate the relative impact of demographic, health, and assistance needs on assessor recommendations, several pseudo r2 statistics and information criterion measures were calculated. Specifically, McFadden, Cox-Snell, and Cragg-Uhler pseudo r2 measures were used, where higher r2 values indicate improved model fit. AIC and BIC information criterion statistics were also included, and Raftery’s procedure [39] was followed to assess model fit improvements. Detailed discussions of these measures can be found in Long [40].

To account for potential intragroup correlation due to individuals having multiple ACAP assessments, cluster-robust variance estimates were produced to ensure corrected standard errors and variance-covariance matrix of estimators. Standard post-estimation testing was used to confirm the validity of the statistical models. Initially, two model types were estimated: one using counts of health condition types and ADLs, and a second model including individual ADL and health conditions. These variable sets were not combined in the same model due to multicollinearity concerns. Model selection tests strongly favored the individual conditions and individual ADL models [39]. However, parameter coefficients for separate models using count variables are also reported in the text to contextualize the detailed regression results. Condition tests were performed post-model fitting to ensure the absence of multicollinearity due to ICD and ADL type inclusion, and the resulting condition numbers were very low, supporting the model specification. This rigorous statistical approach helps to isolate the influence of factors considered within the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 on long-term care recommendations.

Results

Of the 492,398 completed ACAP assessments for individuals aged 65 and over between 2010 and 2013, the majority of recommendations were for long-term care settings in private residences (54%) or residential care (40%) (Table 3). Independent living accounted for a further 4% of recommendations, while community accommodation, hospitals, other institutional care, and other settings each represented less than 1% (0.6%, 0.1%, 0.01%, and 0.9%, respectively). Although the proportions for settings outside private residences and residential care are small, they still represent a significant number of older Australians. For instance, approximately 20,412 recommendations were for independent living and nearly 3,000 for community accommodation. These figures highlight the practical outcomes of applying principles outlined in the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 on a large scale.

Table 3. Current living arrangement by recommended long term care setting (%), 2010–2013.

| Current Living Arrangement1 | |

|---|---|

| Private | Independent |

| Residence | Living |

| % | |

| Recommended Long Term Care (RLTC) Setting | |

| Private Residence | 61.5 |

| Independent Living | 0.5 |

| Community Accomodation | 0.2 |

| Residential Care | 36.9 |

| Hospital | 0.0 |

| Other Institutional Care | 0.0 |

| Other | 0.8 |

| Total | 100 |

| n = | 419264 |

| % | 85.1 |

Notes:

1 The measure of the clients living arrangement collected by the ACAT assessor is their usual accommodation setting. If the ACAP assessment is conducted away from the usual accommodation setting and is temporary in nature, the assessor records the usual setting, not the place of the ACAP assessment. For example, if a person who usually resides in a private residence is assessed while temporarily in hospital, the usual accommodation setting is coded as private residence.

2 Includes 468 cases where current living arrangement is unknown.

Notably, there were significant differences in RLTC settings based on the client’s current living arrangement. Approximately 60% of individuals currently in a private residence received a private residence RLTC recommendation, and a further 37% were recommended for residential care. For those already in residential care, about 98% were recommended to remain in that setting. Similarly, high proportions of individuals currently in hospitals (87%) or other institutional care (86%) were recommended for residential care. This data indicates a degree of consistency in recommendations based on current living situations, reflecting the practical considerations likely embedded within the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

Bivariate comparisons across the population aged 65 and over revealed important demographic differences among those recommended for different RLTC settings (Table 4). Compared to those recommended for private residences, individuals in independent living or other care settings were more likely to be female. Older individuals were more likely to be recommended for non-private residence settings, except for other institutional care. Cultural identity also showed strong associations with RLTC setting. Indigenous Australians were overrepresented in community accommodation, while those born overseas were less likely to be in independent living, community accommodation, or residential care compared to private residence. Unsurprisingly, the presence of a co-resident carer or family member was strongly linked to receiving a private residence RLTC recommendation. These demographic variations underscore the need for nuanced application of guidelines like the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 to diverse populations.

Table 4. Demographic, health and need (ADL) characteristics by recommended long term care setting (%), 2010–2013.

| Recommended Long Term Care (RLTC) Setting |

|---|

| Private |

| Residence |

| Sex |

| Male |

| Female |

| Age |

| 65–74 |

| 75–84 |

| 85+ |

| Cultural Identity |

| Australian Born—Non Indigenous |

| Australian Born—Indigenous |

| Born Overseas |

| Lives in the Community |

| No |

| Yes |

| Family in the Household |

| No |

| Yes |

| Carer |

| No |

| Carer Coresident |

| Carer Non-coresident |

| Health Conditions |

| No ICD Conditions reported |

| Circulatory system diseases |

| Abnormal laboratory findings |

| Muscosceletal system |

| Mental & behavioural disorders |

| Endocrine, nutritional & metabolic |

| Digestive system diseases |

| Genitourinary diseases |

| Eye & adnexa diseases |

| Respiratory system diseases |

| Neoplasms |

| Congenital malformations |

| Ear & mastoid diseases |

| Nervous system diseases |

| Skin & subcutaneous diseases |

| Blood diseases |

| Not elsewhere specified |

| Infections & parasitic diseases |

| Perinatal conditions |

| Mean Health Conditions |

| Assistance Needs |

| ADL Move |

| ADL Moving |

| ADL Communication |

| ADL Health |

| ADL Self Care |

| ADL Transport |

| ADL Social |

| ADL Domestic |

| ADL Meals |

| ADL Home |

| ADL Other |

| Mean ADL |

| Total |

| Distribution (%) |

Notes:—comparison case for tests of proportions

** p

*p

p

In addition to demographic factors, RLTC setting varied significantly with health conditions and ADL assistance needs. Particularly strong differences were observed for mental and behavioral disorders, including dementia and schizophrenia, consistent with prior Australian and international research [41–42]. For example, 38% of those with a private residence RLTC had a mental or behavioral disorder, compared to over 50% of those recommended for residential care or other institutional care. High proportions of neoplasms were found in individuals recommended for hospital (37%) or other institutional care (30%) settings. Across the entire assessed population, circulatory system diseases (82%), abnormal laboratory findings (67%), and musculoskeletal system and connective tissue diseases (56%) were highly prevalent. These health condition patterns are crucial considerations within the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

Supporting the ICD-based differences, considerable variations in RLTC setting were evident based on ADL assistance needs. Except for home maintenance ADLs, individuals recommended for residential care consistently showed higher ADL needs across all categories compared to those in private residences. For instance, 42% of residential care RLTC recipients needed ADL assistance for body movements, compared to under 20% in private residence settings. These ADL needs are directly assessed and considered as per the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

While these bivariate comparisons illustrate clear differences in RLTC settings related to demographic and health characteristics, the magnitude of these differences could be obscured by confounding variables. For example, the strong ADL differences might be partly attributable to increased needs associated with advancing age. To isolate these effects, a multinomial logit model was estimated, using private residence settings as the comparison group (Table 5). The first column of Table 5 presents the determinants of receiving an independent living RLTC recommendation versus a private residence recommendation. Subsequent columns present relative risk ratios for community accommodation, residential care, hospital, other institutional care, and other settings, each compared to private residence. These relative risk ratios demonstrate the association between each variable and the odds of being recommended for an RLTC other than a private residence.

Table 5. MNL regression model of recommended long term care settings.

| Comparison = Private Residence |

|---|

| Independent |

| Living |

| Demographic Factors |

| Male |

| Female |

| 65–74 |

| 75–84 |

| 85+ |

| Non Indigenous |

| Indigenous |

| Born Overseas |

| Lives in Community—No |

| Yes |

| Family/Others in the Household—No |

| Yes |

| Carer—No |

| Carer Coresident |

| Carer Non-coresident |

| Health Conditions |

| Infections & parasitic diseases |

| Neoplasms |

| Blood diseases |

| Endocrine, nutritional & metabolic |

| Mental & behavioural disorders |

| Nervous system diseases |

| Eye & adnexa diseases |

| Ear & mastoid diseases |

| Circulatory system diseases |

| Respiratory system diseases |

| Digestive system diseases |

| Skin & subcutaneous diseases |

| Muscosceletal& connective tissue |

| Genitourinary diseases |

| Perinatal conditions |

| Congenital malformations |

| Abnormal laboratory findings |

| Not elsewhere specified |

| Assistance Needs |

| ADL Move |

| ADL Moving |

| ADL Communication |

| ADL Health |

| ADL Self Care |

| ADL Transport |

| ADL Social |

| ADL Domestic |

| ADL Meals |

| ADL Home |

| ADL Other |

| Constant |

Notes:

** p

*p

p

Relative Risk Ratios for demographic factors largely reinforced the bivariate findings, even after controlling for other variables. Increasing age significantly reduced the likelihood of a private residence RLTC setting. For instance, individuals aged 85 and over were over 3 times more likely to be recommended for independent living compared to private residence (RRR = 3.1, p<0.001). Indigenous Australians were significantly less likely to be recommended for independent living (RRR = 0.18, p<0.001) but 2.8 times more likely to be recommended for community accommodation (RRR = 2.80, p<0.01) compared to non-Indigenous Australians. Living in the community at the time of assessment drastically reduced the odds of being recommended for any non-private residence setting, with RRRs ranging from 0.03 for independent living to 0.52 for residential care (all p<0.001). The presence of a co-resident carer was significantly associated with lower odds of being recommended for residential care (RRR = 0.48, p<0.001) or hospital settings (RRR = 0.33, p<0.001). These demographic influences are crucial to consider when interpreting the application of aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

Controlling for these demographic differences, health conditions remained strongly associated with RLTC settings. Specific disease types showed varying relationships with different RLTC settings. For example, a hospital RLTC setting was significantly associated with neoplasms (RRR = 1.71, p<0.01) and perinatal conditions (RRR = 5.83, p<0.01). Mental and behavioral disorders significantly increased the odds of recommendations for community accommodation (RRR = 1.40, p<0.01), residential care (RRR = 1.70, p<0.001), and other institutional care (RRR = 1.52, p<0.01), highlighting the critical role of mental health considerations within the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

Independent of health conditions, ADL assistance needs were strongly predictive of recommended RLTC settings. Residential care RLTC recommendations, in particular, were associated with multiple ADL types. With the exception of domestic and home ADLs, individuals recommended for residential care were significantly more likely to require assistance with all other ADLs. The associations were particularly strong for self-care (RRR = 2.14, p<0.001), body movement (RRR = 2.16, p<0.001), and moving (RRR = 1.27, p<0.001). These strong correlations underscore the central role of ADL assessments in the framework of the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

To summarize the relative importance of demographic factors, assistance needs, and health conditions on assessor recommendations, scalar measures of fit were calculated (Table 6). Whether these variable sets were introduced individually or additively, the results consistently indicated the substantial explanatory power of assistance needs (ADLs) in predicting assessor recommendations. For instance, the baseline demography model had a Cragg-Uhler r2 of approximately 0.154, which doubled to 0.319 when ADL factors were added. This significant improvement in fit was mirrored by a corresponding decrease in both AIC and BIC statistics. Following Raftery’s approach [39], this provides strong evidence for the substantial contribution of ADLs beyond demographic characteristics. Adding health conditions to the model further improved the pseudo r2 and reduced information criterion measures, indicating enhanced model fit. However, the relative improvement was less pronounced compared to the addition of ADLs. In summary, these results emphasize the primary role of ADLs in assessors’ determinations of recommended care settings, reflecting the practical emphasis of aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

Table 6. Measures of fit, demography, assistance needs and conditions.

| Pseudo r2 | Information Criterion | |

|---|---|---|

| McFadden | Cox-Snell | |

| Single Models | ||

| Demography Only | 0.076 | 0.129 |

| ADL Only | 0.094 | 0.157 |

| Conditions Only | 0.025 | 0.045 |

| Additive Models | ||

| Demography | 0.076 | 0.129 |

| Demography + ADL | 0.171 | 0.267 |

| Demography + ADL + Conditions | 0.185 | 0.286 |

Notes: Single Models–groups of covariates introduced individually. Additive models–groups of covariates added sequentially.

Discussion

Key findings

With the global population ageing trend, the escalating demands on residential and home care services are poised to become a defining challenge in the coming decades. A critical gap in understanding the ACAP process, particularly in the context of aged care assessment program guidelines 2015, has been the decision-making process of ACAT teams regarding RLTC recommendations for community, residential, or institutional care. This study investigated: (i) the distribution of RLTC settings between 2010 and 2013; (ii) the variation of these recommendations based on clients’ demographic and health characteristics; and (iii) the influence of ACAT-determined assistance needs (ADLs) and carer availability on RLTC setting recommendations, within the operational framework of guidelines such as the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

Reflecting the preferences of most older Australians to receive care in their communities rather than institutions [43], the study revealed that slightly over half of all RLTC recommendations were for private residences. For individuals currently living in private residences, this figure was even higher (61%). However, the analysis also highlighted significant variations in RLTC settings based on clients’ current living arrangements. Individuals currently in residential care, hospitals, or other institutional care were rarely recommended to return to private residences. The majority in these categories were recommended for residential care. Only those in independent living (retirement villages) showed a notable minority (20%) recommended to return to private residences. This finding suggests that once a care setting recommendation is made outside of a private residence, a return to private residence becomes less likely. This pattern provides evidence that ACAT teams, guided by frameworks such as the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015, generally make reasonable RLTC setting recommendations based on the assessed needs and current situation.

Beyond the ACAP process context, living arrangement decisions are significant for broader reasons. Gerontological research underscores that living arrangements are key predictors of well-being and needs in later life [44–45]. In the absence of strong familial support, many older Australians require additional resources to meet unmet needs, placing increased pressure on government services [44]. The findings from this administrative data analysis strongly support the role of partners and carers in influencing RLTC settings. This is consistent with descriptive evidence from cohort studies showing that 80% of community-dwelling individuals undergoing ACAP assessments had carers [46]. Having a partner or co-resident carer was significantly associated with private residence recommendations and negatively associated with residential care, hospital, or other institutional care recommendations. This is particularly relevant given projections indicating a significant rise in older Australian males living alone in the community [4]. This trend suggests a potential future increase in demand for institutional and home care due to reduced informal carer availability within households. Policy and guidelines, including the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 and subsequent iterations, must adapt to these evolving demographic realities.

The observed associations between ADLs and care settings reflect the toolkit used by ACAT assessors, designed to capture a broad spectrum of health conditions and assistance needs. As expected, multiple ICD types were clustered in residential care RLTC settings. While hospital settings showed fewer associations with multiple condition types, the conditions tended to be more severe, such as neoplasms and perinatal conditions. Independent living RLTC settings generally showed weaker odds ratios, with some exceptions like nervous system diseases. These patterns demonstrate the nuanced application of criteria within the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

The modeling approach used in this study allowed for examining the independent contribution of ADL assistance needs to care setting recommendations, separate from clients’ health conditions. Moreover, scalar fit statistics highlighted the primary influence of ADLs on assessor recommendations. These findings reinforce the conclusion that ACAT teams prioritize ADLs as key determinants in final RLTC recommendations, aligning with the focus of the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015. Compared to private residence settings, residential care RLTCs showed the highest concentration of ADLs, particularly for self-care, body movement, mobility, and health assistance. Hospitals and other institutional settings followed. Independent living RLTC settings tended to be associated with fewer ADLs, primarily focusing on assistance with meals and domestic tasks.

The clustering of ICDs and ADLs in residential care, hospitals, and other institutional care settings is significant considering the projected increase in comorbidities and longevity in future aged populations [47]. This implies a likely increase in demand for these RLTC settings, irrespective of population growth due to ageing. In this context, enhanced policy focus on coordinated care and complex condition management within communities may help alleviate pressure on these RLTC settings, particularly residential care. However, the data clearly demonstrate that current institutional care clients have substantial care needs requiring complex clinical care, often unsuitable for community settings due to limited timely access to primary health care, especially in rural areas. Therefore, policymakers must consider both expanding community care options and anticipating increased demand for residential aged care beds. Future iterations of guidelines, building upon the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015, must address these dual challenges.

Future research priorities

The patterns and associations identified between ADL types and severity, ICDs, and RLTC settings provide substantial evidence supporting the evidence-based nature of ACAP recommendations and their alignment with the ACAP toolkit and guidelines. The findings suggest several avenues for further research to enhance the effectiveness of ACAT recommendations and the broader aged care system.

Firstly, the administrative data used in this study does not link ACAT recommendations to actual admissions or entry into residential care or other programs like flexible care packages. While some cohort analyses on care pathways have been conducted by the AIHW [46], further multivariate analysis is needed to understand the drivers of these pathways and the determinants of ACAT recommendations that lead to care utilization. Relatedly, evaluating the efficiency of ACAT recommendations requires understanding the regional supply and availability of services. Ideally, data at the Aged Care Planning Region (ACPR) level would be necessary for such analysis. Unfortunately, geocoded information was unavailable for this study due to confidentiality concerns. Geographic service availability, influenced by factors like remoteness, could significantly affect waiting times for residential care admission or redirect individuals towards community care arrangements. Indeed, ACAT assessors are instructed to “note that a care service is available if there are allocated places in the area, regardless of whether there is a vacancy at the time of the assessment and approval of the clients” [28], indicating that geographic availability is considered in recommendations, and should be further explored in conjunction with guidelines like the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015.

Secondly, analyzing the impact of ACAT skill mix and the availability of client medical records on ACAT recommendations would strengthen existing guidelines. Policy guidelines stipulate that ACATs should have access to diverse skills and expertise, including geriatricians, specialists, GPs, nurses, social workers, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, and psychologists. Investigating the relationship between assessor skill mix and care recommendations and approvals could reveal how different assessor compositions influence recommendations. Furthermore, with client consent, ACATs can access medical records from GPs and other health professionals. Analyzing the association between medical file availability and the efficiency of care recommendations could inform policy guidelines for ACATs. International research suggests that detailed medical information improves care placement [48–49], and future iterations of the aged care assessment program guidelines could benefit from incorporating insights into optimal information utilization.

More broadly, the study’s findings are crucial for projecting future demands on the Australian aged care system. The varying determinants (demographic, health, and assistance needs) of different RLTC settings indicate that standard demographic projections with limited covariates are unlikely to accurately estimate residential care populations and the care needs of older Australians. This raises questions about the types of models needed to project care demand in community and non-community settings in Australia. Specifically, how can the growing collections of ACAP and other administrative data be linked with survey, census, and demographic data to better understand service demands and gaps in the aged and community care sectors? Moreover, how can governments and researchers leverage modern econometric and data mining techniques to improve understanding of care trajectory pathways and inform future guidelines, building upon the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015?

The data for this study became available during a period of significant reform in the Australian aged care system, addressing long-term financing and workforce issues also facing long-term care in the US [50]. A central reform is the introduction of a consumer-directed care (CDC) model aimed at enhancing consumer choice and flexibility. However, CDC implementation is likely to encounter challenges, particularly in rural areas where low population density can threaten the viability of aged care facilities, increase service delivery costs, and limit older individuals’ access to services. Future releases of ACAP administrative data should be analyzed to assess whether assessor recommendations have evolved since the period examined in this study and how guidelines like the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 have been adapted and impacted by these reforms.

Despite limitations and potential extensions, the results of this study demonstrate that approximately half of ACAT recommendations are for community-based care settings, that assistance needs (ADLs) are a dominant factor in assessor recommendations, and that the clustering of ADLs and diseases in residential care and hospital settings supports the evidence-based nature of ACAP assessments. Further research into the determinants and constraints of ACAT recommendations, particularly concerning regional service availability, can strengthen existing policy guidelines for assessors. This has the potential to enhance the efficiency of the Australian aged care system, ultimately improving the health and well-being of older Australians, their carers, and families. Continued refinement of frameworks like the aged care assessment program guidelines 2015 is essential to meet the evolving needs of Australia’s ageing population.

Data Availability

The de-identified dataset used for this article was provided to the authors by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, who control access. The authors do not have the legal right to distribute or provide access to the data set. Only the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare can grant access to the data, and the authors did no have any special privileges to the data. To be considered for access to this database, please contact: https://www.aihw.gov.au/about-our-data/our-data-collections/national-aged-care-data-clearinghouse.

Funding Statement

MJ received funding support from the Australian Research Council’s (ARC) Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR) CE1101029. JT is funded by the Australian Research Council’s (ARC) Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research (CEPAR) CE1101029. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The de-identified dataset used for this article was provided to the authors by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, who control access. The authors do not have the legal right to distribute or provide access to the data set. Only the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare can grant access to the data, and the authors did no have any special privileges to the data. To be considered for access to this database, please contact: https://www.aihw.gov.au/about-our-data/our-data-collections/national-aged-care-data-clearinghouse.