Introduction

The global population is aging rapidly. In 2021, over 962 million people were aged 60 and above, and projections indicate this number will reach 2 billion by 2050 (Age International, 2021). This demographic shift, while a testament to increased life expectancy, brings with it a rise in age-related co-morbidities and a subsequent surge in demand for robust health and social care systems (NIHR Evidence, 2018). Many countries, particularly within the EU, have responded by reforming care policies to expand community-based long-term care services. This strategic move aims to deliver effective care for older adults, alleviate pressure on informal caregivers, and optimize the use of broader health services (Hattink et al., 2015). However, these policy adjustments occur against a backdrop of significant concerns regarding the capacity and caliber of the aged care workforce (CQC, 2020; OECD, 2022). Central to these concerns is the adequacy and relevance of training provided to those working in long-term care (Health and Social Care Committee, 2021). Notably, in many OECD nations, non-registered long-term care professionals often lack sector-specific training (OECD, 2022). Even when training is provided, questions remain about its effectiveness in equipping staff with practical, enduring skills (CQC, 2020).

In England alone, the domiciliary care sector employed approximately 510,000 direct care workers in 2020/2021, including senior care workers, care assistants, and community support staff (Skills for Care, 2021). This expanding workforce is characterized by increasing diversity in roles, skills, and qualifications (Wilberforce et al., 2017). Non-registered care staff operate across various settings—from private homes to hospices and residential care facilities (Cavendish, 2013)—undertaking roles such as home care workers, nursing assistants, and social work assistants (Wilberforce et al., 2017). Their responsibilities are broad, encompassing support for daily living activities, personal care, and social engagement, often delivered under challenging and demanding conditions (Newbould et al., 2021).

Globally, there is a notable absence of universal standards regarding the required level of training for these essential support staff, with significant variations across countries (OECD, 2022). In the UK, access to vocational training for support-grade staff has historically been contingent on government funding. Following a prominent national care scandal, recommendations were made to ensure core training provisions for all such staff (Cavendish, 2013). Despite these efforts, persistent concerns linger about the appropriateness of existing training programs. Criticisms include training being overly advanced and geared towards clinically qualified personnel, or conversely, too basic, focusing merely on introductory ‘awareness’ (CQC, 2020; Herber & Johnston, 2013; Wilberforce et al., 2017). Consequently, many services rely on in-house or private training solutions (Surr et al., 2017), leading to potentially high costs for care providers and a lack of consistent oversight of training quality (Greater Manchester Health and Social Care Partnership, 2017).

The development of effective training for the homecare workforce is hampered by a lack of robust, evidence-based approaches. Despite a substantial body of educational theory (Khalil & Elkhider, 2016), the optimal design of learning interventions for this critical workforce remains poorly understood. Existing systematic reviews often suffer from narrow scopes, focusing predominantly on dementia care (Eggenberger et al., 2013; Surr et al., 2017) or specific user needs (Higgins et al., 2019; Jurček et al., 2020), thereby overlooking broader, generalizable insights (Smith et al., 2011). While some attempts have been made to synthesize literature on training needs for homecare workers supporting individuals with dementia and cancer (Cunningham et al., 2020), these often exclude the wider non-registered social care workforce. Therefore, further investigation is crucial to assess, synthesize, and extrapolate the essential components of effective learning for non-registered practitioners in long-term care. This synthesis will better inform the design and development of future, impactful learning interventions.

To address this gap, a review of reviews methodology was employed. This approach allows for a comparative analysis of existing reviews, considering their quality, to synthesize learning components from a diverse range of interventions, and to identify the strongest evidence for effective learning design (Smith et al., 2011). The findings are synthesized using the Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (ADDIE) framework (Mayfield, 2011), specifically to inform the critical analysis phase of learning intervention design.

Methods

Aim and Research Questions

This review of reviews aimed to identify and synthesize evidence that supports the design of learning interventions for non-registered practitioners who provide care to older people in long-term care settings.

The primary objectives were to gather evidence on five key components of learning design:

- Content: What should be taught?

- Format: Which teaching strategies and resources/media are most effective?

- Structure: How should the learning be organized and sequenced?

- Contextual Factors: What barriers and enablers influence learning effectiveness?

- Measures of Effectiveness: How is the success of learning interventions monitored and evaluated?

Search Strategy

The search strategy (detailed in Table S1 of the original article’s supporting information) was developed based on prior similar reviews (Dickinson et al., 2017; Frost et al., 2018; Surr et al., 2017; Wells et al., 2020) and expert consultation with a learning development specialist at the Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE). Databases searched included ProQuest (ASSIA), Scopus, Ovid (PsycINFO, Medline, Embase, and Social Policy and Practice), SCIE Online, Cochrane Reviews, and reference lists of identified articles.

Search terms were categorized into four groups: population (non-registered practitioners), intervention (learning), context (community setting), and method (review terms). The search was refined using “NOT ‘child*’” and age filters to focus on older adults. Keywords were searched in titles and abstracts, and reference lists were manually scanned for additional relevant reviews. The final search was conducted in April 2021.

Eligibility and Screening

A review of reviews approach was chosen to ensure the consistency of findings on intervention efficacy. This method allows for the identification and separate synthesis of high-quality reviews if inconsistencies in conclusions are found (Smith et al., 2011).

Inclusion criteria for reviews were:

- Focus on learning interventions for non-registered practitioners supporting older people.

- Settings including people’s own homes, hospices, or nursing/residential care facilities.

- Study designs encompassing systematic reviews, meta-analyses, narrative reviews, scoping reviews, and Cochrane reviews.

- Synthesis of findings from multiple primary studies.

- Focus on the relationship between training components (content, structure, format, delivery mechanism) and associated outcomes.

- Publication date from 2000 onwards.

- Any country of origin.

- English language publication.

Exclusion criteria were:

- Focus on training for professionally qualified staff.

- Focus on care for younger populations.

- Non-English language publications.

- Settings limited to hospital/clinical environments.

- Reviews not collecting outcome data.

- Reviews not focused on learning interventions.

- Reviews of reviews.

Retrieved papers were imported into Covidence (https://www.covidence.org/). One researcher (L.N.) screened titles and abstracts. To ensure consistency and refine eligibility criteria, three randomly selected full-text articles were further reviewed by the research team (L.N., M.W., K.S.) before proceeding with full-text screening by L.N.

Quality Appraisal

The quality of included reviews was assessed by one researcher (L.N.) using the AMSTAR 2 checklist. AMSTAR 2 was selected due to its high inter-rater reliability and usability (Gates et al., 2020), and its suitability for assessing reviews of both randomized and non-randomized studies (Pieper et al., 2019; Shea et al., 2017).

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data synthesis was structured using the ADDIE framework, a widely used instructional design model for developing training courses (Mayfield, 2011; Vejvodová, 2009). The ADDIE framework includes five phases: Analysis, Design, Development, Implementation, and Evaluation (Peterson, 2003; Vejvodová, 2009). In this review, findings were synthesized to inform the analysis phase of learning design, providing a comprehensive overview for instructional development.

Data extraction was performed by one researcher (L.N.) using Excel. Extracted data included: author, year of publication, review aim, review type, number of included studies, target group, intervention objectives, synthesis methods, successful and unsuccessful intervention components (content, format, structure, objective realization), and outcomes.

The extracted data was then synthesized to identify key intervention components influencing learning effectiveness. These components were categorized into content, format (media and teaching strategies), structural elements (e.g., session length), and environmental factors impacting learning objective realization.

Reporting

This review was conducted by the research team in collaboration with an advisory group and adhered to PRISMA guidelines (Liberati et al., 2009).

Results

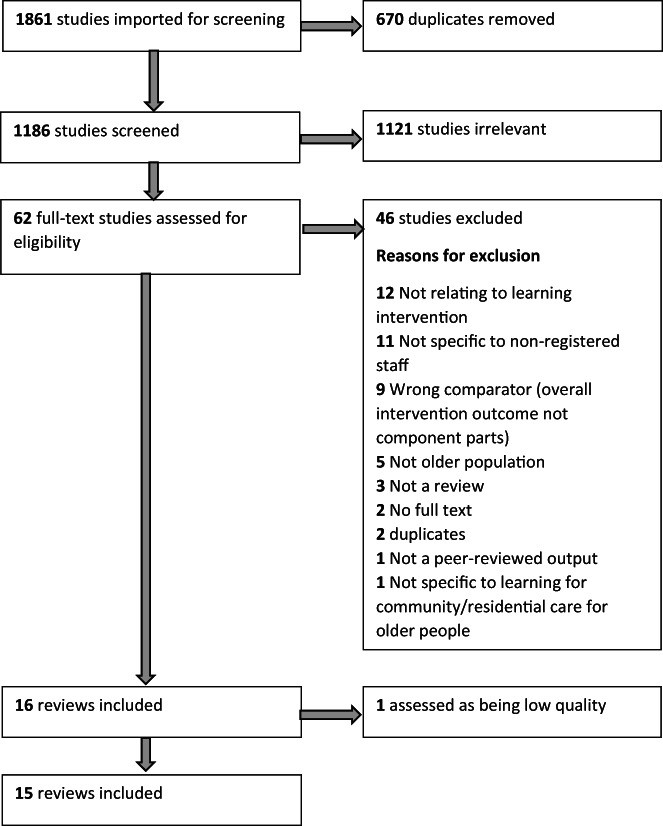

The flow diagram in Figure 1 illustrates the screening process, including reasons for excluding reviews.

FIGURE 1. Flow diagram of the review screening process

FIGURE 1

FIGURE 1

Table 1 summarizes the PICO components for learning interventions within the included reviews.

TABLE 1. PICO components of learning interventions in included reviews

| Author | Papers included (no.) | Synthesis Method | Population (Target Group) | Intervention (Objective Analysis)