Background

The landscape of healthcare, particularly in aged care settings, is becoming increasingly complex, demanding a higher level of expertise and adaptability from nursing professionals [1, 2]. For newly graduated registered nurses (NGNs), the transition from academic learning to practical application in aged care can be particularly challenging and stressful [3]. This transition is marked by heavy workloads, significant accountability, and the critical responsibility of ensuring patient safety and well-being [4]. Recognizing these challenges, transitional support programs and robust clinical supervision models are essential to facilitate the professional development of new graduate nurses, enhance their clinical proficiency, and ultimately improve retention rates within the aged care sector [5]. For aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017, understanding the nuances of this transition was crucial in shaping effective support mechanisms.

To develop impactful aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017, a deep understanding of the clinical environment and workplace conditions experienced by new graduates is paramount. New nurses often enter aged care facilities facing staffing shortages and increasingly complex patient needs [6], sometimes with limited immediate support available [7]. A positive and supportive work environment is known to significantly ease the transition for graduate nurses and boost their job satisfaction [6]. Conversely, negative workplace experiences, such as inadequate support systems or poor supervisory relationships, can lead to heightened stress levels that can persist for a year or more post-graduation. These early career experiences not only affect immediate job satisfaction but also have long-term implications for career commitment and longevity in aged care nursing [5]. Alarmingly, research from the early 2010s highlighted that new graduate nurses still faced similar struggles to their predecessors from a decade prior – struggling to meet expectations, manage heavy workloads, and experiencing stress and burnout [9]. This underscores the continued relevance and urgency of addressing these issues in programs like the aged care graduate nurse programs of 2017.

The initial year of practice in aged care is frequently described by new graduate nurses as overwhelming and stressful. They are tasked with applying newly acquired skills, delivering high-quality patient care, and integrating into a new team environment [10]. Critically, this period also sees significant attrition, with reported rates as high as 27% [11]. These concerns have spurred the development of graduate programs internationally [12], often termed transitional programs, specifically designed to foster clinical competence, support professional growth, and enhance retention among NGNs in various healthcare sectors, including aged care. In 2017, the focus on creating effective transitional programs for aged care was particularly important given the growing demand for qualified nurses in this sector.

Numerous studies have documented the negative impact of workplace stress, incivility, and burnout on the retention of new graduate nurses [9, 11, 13]. The challenge of optimizing newcomer transition in demanding aged care environments remains a critical area of ongoing investigation. While a consensus exists on the necessity of a supportive organizational environment for the successful integration of novice nurses, fewer studies have thoroughly explored the evolving perceptions and experiences of new graduate nurses over time. Bauer, Bodner, Erdogan, Truxillo, and Tucker [14] describe the socialization process, or ‘onboarding,’ that new nurses undergo as they learn the knowledge, behaviors, and attitudes required to effectively perform and adapt to their new work environment [15]. However, factors such as rising patient acuity and understaffing in aged care can negatively affect this onboarding process, sometimes exacerbated by the new graduates’ fear of failure [16]. For aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017, understanding and mitigating these negative impacts was crucial.

Transitional programs are a key intervention to address these challenges. While program formats vary, their core aim is to facilitate the entry of new graduate nurses into the nursing workforce within an institutional setting. Typically spanning 12 months, these programs offer structured experiences including facility and ward orientations, rotations across different aged care settings, dedicated study days, and both formal and informal clinical supervision. These components are designed to help novice nurses consolidate theoretical knowledge, refine critical skills, and strengthen their clinical judgment in their new professional roles within aged care [11]. To ensure a successful transition from novice to competent registered nurse in aged care, structured professional development programs, delivered in a supportive manner, are considered essential [17]. These programs help new graduates integrate into the organizational systems and processes of aged care facilities [7]. For programs implemented in 2017, the focus was on refining these structures to better meet the specific needs of aged care settings.

Given the significant implications for workforce stability in aged care nursing, evaluating the effectiveness of transitional support programs and identifying factors contributing to both positive and negative experiences of new graduates is critical. This study aimed to examine the changes in new graduate nurses’ perceptions throughout a 12-month transitional support program (TSP), also known as a nurse residency program. Specifically, this research sought to: (i) identify the elements of clinical supervision that significantly influenced the experiences of new graduates in aged care during their programs in 2017; (ii) assess the changes in new graduate nurses’ perceptions of clinical supervision, confidence levels, satisfaction with orientation, and their practice environment throughout the 12-month transition period, providing valuable insights for programs in 2017; and (iii) explore the overall experiences of new nurses during this transitional phase, noting any changes between the beginning and end of the program, crucial for informing the design of future aged care graduate nurse programs beyond 2017.

Methods

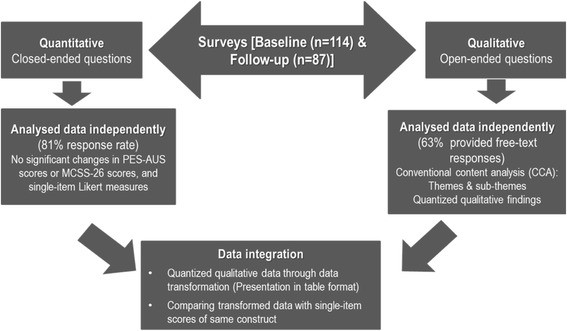

This research employed a convergent mixed methods design as part of a broader project [18] evaluating the efficacy of clinical supervision practices for new graduate nurses in acute care settings, with findings highly relevant to aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017. The integration of quantitative and qualitative data significantly enhances the depth and breadth of research findings [3, 19], providing a more holistic understanding of the experiences of new graduate nurses that can be applied to aged care contexts.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1

Overview of Convergent Mixed Methods Design [3, 19]

This paper integrates quantitative data analysis with qualitative analysis of open-ended survey responses from new graduate nurses enrolled in a transitional support program. Surveys were administered at two key points: initially at 8–10 weeks after the program began, and again at 10–12 months. These time points were strategically chosen to align with scheduled study days, ensuring participants had sufficient experience in their rotations to effectively reflect on their transitional journey and clinical competence. This methodology provides a robust framework for understanding the experiences within aged care graduate nurse programs and can be adapted for evaluations in 2017 and beyond.

Study Setting and Participants

The study was conducted at a major referral and teaching hospital in Sydney, Australia. This hospital, with 855 beds and over 1500 nursing staff across various specialties, represents a complex acute care environment. All new graduate nurses (n = 140) enrolled in the 12-month transitional support program at this institution were invited to participate. Recruitment occurred during facility orientation, study days, and via email invitations. Programmed study days are integral to the transitional support program, providing structured learning opportunities for new graduates. ‘Orientation days’ refer to the period when new nurses were given supernumerary status on wards, working alongside or being preceptored by experienced registered nurses or clinical nurse educators. Data collection spanned from May 2012 to August 2013, utilizing group TSP study days, shift overlap times, and other convenient times to ensure participant accessibility. Participants completed self-report instruments independently. While the setting is acute care, the program structure and challenges faced are highly informative for designing and evaluating aged care graduate nurse programs, including those in 2017.

Data Collection

Participant characteristics assessed included: (i) age; (ii) gender; (iii) history of previous paid employment; and (iv) prior nursing experience. Single-item Likert scale measures were used to assess the frequency with which NGNs felt under-confident or placed in situations beyond their clinical capabilities (0 = never, 10 = always). Three practice environment factors were also evaluated: (i) assigned unit type (critical care or non-critical care); (ii) satisfaction with unit-based orientation (single-item question); and (iii) satisfaction with clinical supervision within the TSP. Participants were encouraged to justify their ratings or provide examples for single-item measures. Additionally, two validated instruments were administered at baseline and follow-up: the 26-item Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale (MCSS-26) to assess NGN perceptions of clinical supervision quality [[20](#CR20]], and the Practice Environment Scale – Australia (PES-AUS) to gauge satisfaction with the clinical practice environment [[21](#CR21]]. The PES-AUS was modified to include a midpoint of 3 = ‘unsure,’ acknowledging that new graduates might not be familiar with all scale items. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for both instruments was high (0.90 and 0.91 respectively), indicating strong internal consistency. These tools and methodologies are directly applicable for assessing the effectiveness of aged care graduate nurse programs, such as those in 2017.

Ethics approval was obtained from Western Sydney University and South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committees (H10055, LNR/11/LPOOL/510). All participants provided written informed consent. Permission to use the MCSS-26 and PES-AUS was granted by the respective authors.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22 [4]. Normality for continuous variables was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and data were expressed as medians and ranges. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Changes between baseline and follow-up were examined using Pearson’s chi-square for categorical variables, and paired t-tests or Wilcoxon signed-rank tests for continuous variables. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Conventional Content Analysis (CCA) was used to analyze open-ended responses. This method allows themes to emerge directly from the data rather than being predetermined [22]. The first author (RH) repeatedly read the open-ended responses for immersion [22]. Frequently used words (e.g., support, workload, skills) were identified and highlighted in Excel to denote key aspects of experiences and transition. Initial impressions formed the basis for developing categories or ‘sub-themes’ under broader ‘themes’.

Two researchers (RH and LR) reviewed open-ended responses to single-item measures for emergent themes. Initially, 20% of free-text responses were independently coded by two researchers (RH & YS) into positive or negative aspects of preliminary themes. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion to achieve consensus before continuing coding. RH completed the remaining coding. Data integration was achieved by ‘quantitizing’ qualitative data into numerical form [19].

Using six subthemes as categories, frequencies of free-text responses were grouped into positive and negative dimensions, based on the number of times a code referring to a sub-theme appeared in a participant’s survey. A numerical value of “1” was assigned for each positive comment and “0” for negative. Aggregate scores were computed for each subtheme (Table 1). Qualitative responses were thus ‘transformed’ into quantitative data and integrated with illustrative examples from the original dataset [23]. These analytical approaches offer valuable models for evaluating both quantitative and qualitative outcomes of aged care graduate nurse programs, including those implemented in 2017.

Table 1.

Positive and negative comments of new graduate nurses at baseline and follow-up

| Theme | No. | Category | Frequency of comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | ||

| Positive | Negative | Balance | Positive |

| 1. Orientation and Transitional Support Program as foundation for success | 1.1 | Instrumental support during transition | 33 (43%) |

| 1.2 | Understanding the clinical capabilities of the new graduate | 14 (18%) | 31 (19%) |

| 1.3 | Becoming one of the team or part of the team | 3 (4%) | 3 (2%) |

| 2. Developing clinical competence | 2.1 | Appropriate workload and working within scope of practice | 8 (10%) |

| 2.2 | Adequate skill mix | 9 (12%) | 11 (6%) |

| 2.3 | Building clinical confidence and competence | 10 (13%) | 39 (23%) |

| Subtotal | 77 (100%) | 167 (100%) | −90 |

| Baseline Balance | Follow-up Balance |

Results

Quantitative Findings

Sample Characteristics

Of the 140 new graduate nurses enrolled, 114 (81%) completed the baseline survey, and 87 of these (76%) completed the follow-up surveys. No statistically significant differences were found in age, MCSS-26, or PES-AUS scores between those who completed follow-up and those who did not.

The median age was 23 years (range: 20 to 53), and over three-quarters of the sample were female (78%). More than half had prior nursing experience, mainly as Assistants in Nursing (AINs). During the program’s two rotations, approximately 63% worked in non-critical care areas, while 37% were in critical care. These demographic characteristics are typical of new graduate nurse cohorts and provide context for understanding the results, applicable to considerations for aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017.

Experiences Over Time: Baseline vs Follow Up

No significant change was observed in new graduate nurses’ satisfaction with clinical supervision over the two time periods (mean MCSS-26 scores: 73.2 vs 72.2, p = 0.503). Similarly, no significant differences were found in: (i) satisfaction with the clinical practice environment (mean PES-AUS scores: 112.4 vs 110.7, p = 0.298); (ii) overall satisfaction with the transitional support program (mean: 7.6 vs 7.8, p = 0.337); (iii) satisfaction with the number of study days (mean: 4.4 vs 4.7, p = 0.72); (iv) orientation days received (mean: 6.4 vs 6.6, p = 0.541); (v) unit orientation (mean: 4.4 vs 4.8, p = 0.081); (vi) confidence levels (mean: 3.6 vs 3.5, p = 0.933); and (vii) not practicing beyond personal clinical capability (mean: 3.9 vs 4.0, p = 0.629). These quantitative findings suggest a consistent level of satisfaction across the program duration, which is important for benchmarking aged care graduate nurse programs, including those in 2017.

Qualitative Findings

Nearly two-thirds of participants, n = 72 (63%), provided free-text responses at baseline and/or follow-up. Two primary themes, each with three subthemes, emerged, encapsulating their experiences during the transitional period. These are detailed in Table 1 and further elaborated below with illustrative quotes, providing valuable qualitative insights for enhancing aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017.

Theme 1: Orientation and TSP as a Foundation for Success

A majority of respondents emphasized the critical role of the transitional support program and orientation in ensuring a successful transition. Participants who felt well-supported during their supernumerary period and orientation reported feeling “formally introduced to the team which was satisfying and welcoming for new staff.”

Overall the TSP team have provided a great deal of clinical and emotional support throughout the year. The program has been useful in transitioning into the hospital setting (Participant 2.35).

This highlights the fundamental importance of robust orientation and support structures in transitional programs, lessons highly relevant for aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017.

Sub-theme 1: Instrumental Support During Transition

Consistent support from Clinical Nurse Educators (CNEs), Nurse Unit Managers (NUMs), Clinical Nurse Specialists, and experienced Registered Nurses, in addition to a comprehensive ward or unit orientation, was deemed crucial. This support fostered both acceptance and learning among new graduates.

The support was exceptional. CNE was very thorough and supportive alongside the NUM (Participant 3.6).

Good experiences, worked in a supportive environment, also got continual support after formal orientation (Participant 4.22).

These comments underscore the value of ongoing instrumental support systems within aged care graduate nurse programs, informing best practices for programs in 2017.

Sub-theme 2: Understanding the Clinical Capabilities of the New Graduate

Conversely, some participants felt that ward staff held unrealistic expectations regarding their clinical capabilities, and some received minimal ward orientation, which was unhelpful. Newcomers needed sufficient time to familiarize themselves with ward layouts, equipment, and policies.

I found that I didn’t have very much time to get orientated and was pushed into the deep end (Participant 3.9).

Three Cardiothoracic patients at one given time, 1 pt. on inotropes, noradrenaline and dobutamine. Another post coronary artery bypass graft [CABG], another tracheostomy. Plus there was a met call that day (participant 2.32).

These negative experiences highlight the need for aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017 to ensure realistic expectations and adequate orientation periods are in place.

Sub-theme 3: Becoming One of the Team

Surprisingly, formal introductions to ward or unit staff were not always provided to new graduates. One participant suggested:

Have a day to introduce me to ward (staff) (Participant 4.17).

Despite this, a sense of team integration was also reported:

The ward staff have been very supportive and often give tips/input on what can be done on a particular situation. (Participant 2.9).

Building team integration and a welcoming environment remains a critical component for aged care graduate nurse programs, including those in 2017.

Theme 2: Developing Clinical Competence

Many NGNs felt the transitional support program offered valuable opportunities to develop their clinical competence. However, the availability and quality of these opportunities varied depending on the expertise and availability of TSP coordinators, after-hours nurse educators, ward-based CNEs and specialists, team leaders, and senior staff. This variability, coupled with increasing workloads and skill mix issues, impacted novice nurses’ ability to develop competence. Facing unexpected clinical situations such as MET calls, deteriorating patients, and challenging family interactions were also cited.

I’ve found that I have been put in situations I have had little exposure to with minimal help at hand. Although some senior staff may help, it may take some convincing. (Participant 3.9).

Despite these challenges, some nurses successfully developed their clinical skills:

Two months was enough for me to positively develop skills and knowledge. However, emotionally it was very hard and draining (Participant 4.15).

These mixed experiences underscore the complexity of competence development in transitional programs and are important considerations for aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017.

Sub-theme 1: Appropriate Workload and Working Within Scope of Practice

Unrealistic workloads and expectations due to high patient acuity and staff shortages were common concerns. Some new graduates felt they were working beyond their scope of practice with excessive patient loads.

Ten patients, multiple admissions and discharges, time consuming procedures e.g. dressings, blood transfusions and post-op patients with only an undergraduate nurse (Participant 3.41).

All 5 patients were total nursing care. Had never seen or used the drains, dressings or TPN. No help or not much help available. Ward assumes I know and seem cranky if I say I don’t know… (Participant 3.32).

Workload management and scope of practice are critical issues for aged care graduate nurse programs and were likely significant concerns in 2017.

Sub-theme 2: Inadequate Skill Mix

Participants reported being expected to deliver quality care despite inadequate skill mixes, compounded by high patient acuity, MET calls, and rapid patient turnover. New graduates were sometimes paired with assistants in nursing with limited capacity to provide support, while simultaneously being stretched beyond their own capabilities.

I felt as though it was often new graduate nurses on the ward were allocated unfairly by senior staff members … on numerous occasions new graduates were allocated to the heaviest teams with the casual AINs …while senior staff allocated themselves with ENs and RNs (Participant 2.35).

Addressing skill mix issues is vital for effective aged care graduate nurse programs, impacting both support for new graduates and patient care quality, and was likely a key focus in 2017.

Sub-theme 3: Building Clinical Confidence and Competence

Despite numerous challenges, many new graduates gained confidence in handling emergent situations due to available support.

Had patients needing MET calls for various conditions (VT, VF, desaturation). I did not feel confident taking care of these patients on my own but had help around me at these times (Participant 4.17).

However, others experienced a lack of confidence and struggled to manage complex patient situations.

I felt insecure…. and I was not sure what to do, such as when discharging a patient and what to do when facing an emergency situation although I have been told what to do (Participant 3.16).

A patient (HDU) clinically deteriorated and felt very uncomfortable, useless, dumb as I did not know what to do and the team took over (Participant 4.15).

Building clinical confidence and competence is a central goal of any graduate nurse program, and these insights are crucial for aged care programs, including those in 2017.

Quantized Qualitative Findings

Numerous comments related to ‘Instrumental Support during Transition’ [Subtheme 1.1] at both baseline (Total: 69) and follow-up (Total: 53), with negative comments increasing at follow-up. In ‘Understanding the Clinical Capabilities of the New Graduate’ [Subtheme 1.2], negative comments predominated at both time points, though fewer at follow-up (9 vs 31). Few comments were made about ‘Becoming one of the team’ [subtheme 1.3] at either time.

In Theme 2, most comments regarding ‘Appropriate workload and working within scope of practice’ [subtheme 2.1] were overwhelmingly negative. At baseline, 47 of 55 workload comments were negative (85%), and at follow-up, 36 of 38 (95%) were negative. For ‘Adequate skill mix’ [subtheme 2.2], comments were fewer, with roughly equal positive and negative responses at both time points. Most new graduates expressed a lack of ‘Clinical confidence and competence’ at baseline [subtheme 2.3], but negative comments decreased at follow-up. Overall, free-text responses at follow-up were less negative (Table 1). These quantified qualitative findings provide a nuanced view of the changing perceptions over time and offer specific areas for improvement in aged care graduate nurse programs, relevant to 2017 program design.

Integrated Findings

While quantitative data showed no statistically significant changes in satisfaction with clinical supervision, orientation days, TSP experience, or practice environment, qualitative data suggested increased satisfaction at follow-up. For instance, negative responses about orientation and TSP decreased from 70 at baseline to 42 at follow-up. Similarly, negative comments on ‘building clinical confidence and competence’ dropped from 39 to 22, and those on ‘Appropriate workload and working within scope of practice’ decreased from 47 to 36 (Table 1). This integration of findings points to improvements in perceived satisfaction over time, even if not captured by quantitative scales alone, offering a more complete picture for evaluating aged care graduate nurse programs, including those in 2017.

Discussion

This study aimed to examine new graduate nurses’ perceptions and experiences of clinical supervision within a 12-month transitional support program, and how these changed over time. The findings offer important insights for the development and refinement of aged care graduate nurse programs, such as those implemented in 2017, and beyond.

Contrary to expectations, new graduate nurses’ satisfaction scores (MCSS and PES-AUS) did not increase significantly over the program. This may be due to the initial data collection timing (8–10 weeks post-commencement), possibly after the most challenging initial adjustment period had passed. Duchscher [24] noted that the most intense adjustments occur in the first 1–4 months of a TSP, coinciding with our baseline data collection. Thus, initial scores might reflect that ‘the worst was over’ in terms of initial transition stress. However, the fact that satisfaction did not increase further suggests ongoing challenges and areas for improvement in transitional support, particularly relevant to aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017.

However, the reduced number of negative responses in open-ended questions at follow-up suggests an overall increase in satisfaction by program completion. The discrepancy between quantitative and qualitative findings may indicate that the standardized instruments were not sensitive enough to detect subtle changes in this specific cohort, or that persistent negative experiences (e.g., lack of support, transition shock [25], practice readiness concerns [26], confidence issues [5, 18, 27], stress) influenced follow-up scores despite improvements. Interestingly, a ‘V-shaped’ satisfaction pattern reported by Ingersoll et al. [28], with a dip at 6 months and recovery by 12 months, suggests new graduates adjust after the initial phase. In our study, the transition to a new clinical specialty after the first rotation might have caused renewed feelings of being out of depth, potentially affecting satisfaction scores. These dynamics are crucial for understanding the nuanced experiences within aged care graduate nurse programs and can inform program adjustments in 2017 and subsequent years.

While new graduates were generally satisfied with the number of study days, low satisfaction with unit orientation at both time points (first and second rotations) was concerning. Despite satisfaction with specialty orientations (ICU, PICU, CCU, aged care), many felt orientation time was insufficient, particularly for ward routines, layout, equipment, and policies. Staff expectations of readiness may have been higher in the second rotation, consistent with views that new graduates should be ‘practice-ready’ [29] upon workplace entry [27]. These findings highlight the critical need for improved ward-based orientation in transitional programs, directly applicable to aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017.

Qualitative data reinforced these points, with nurses feeling “thrown in the deep end” (Participant 3.6) or simply “told to read policies” (Participant 3.45). Whether low satisfaction was due to inadequate educator support or other factors like staff shortages or skill-mix issues is unclear. These findings strongly suggest the need for well-structured, ward-based orientation programs tailored to new graduate nurses’ needs, a key consideration for aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017.

Participants reporting satisfactory supernumerary support and orientation also felt welcomed and integrated into their teams, highlighting the importance of ward staff understanding new graduates’ capabilities and avoiding unrealistic expectations. These social and integration aspects are vital for the success of aged care graduate nurse programs and should be emphasized in programs in 2017.

Single-item measures indicated infrequent placement in situations beyond clinical capability or confidence. However, qualitative findings linked staffing ratios, skill mix, patient acuity, support, and workload to instances where new graduates felt overwhelmed. This aligns with prior research on support inconsistencies [9]. The study also revealed that some new graduates felt allocated tasks or patient loads beyond their scope, especially moving from lower-acuity areas (e.g., ICU) to higher-volume wards. This suggests senior staff need to consider NGNs’ prior rotations and experience when assigning workloads, as proficiency in time management and patient load may not automatically transfer from specialty areas. Rush et al. [27] and Duchscher [25] have also noted critical periods of support needs around the 6–9 month mark and a ‘crisis of confidence’ around 5–7 months, respectively, coinciding with the start of the second rotation in this study, which may explain increased negative workload comments. These workload and scope of practice concerns are particularly relevant to aged care settings and must be addressed in aged care graduate nurse programs, including those in 2017.

Encouragingly, participants reported rare instances of feeling unconfident, and when they did, senior support was generally available. Lack of confidence was often linked to workload and skill-mix issues [Subtheme 2.1]. Consistent with other research [30], stressful situations were occasionally reported, and some felt “set up to fail” due to support deficits. Scott et al. [5] emphasize that a supportive environment includes organizational integration, understanding policies, processes, and roles in quality care and safety [6]. Workplace resources, information access, and growth opportunities are crucial for empowerment [30]. Laschinger et al. [13] found that empowerment and workload support reduce burnout risk. Overall, these findings support the value of nurse residency programs in helping newly licensed nurses navigate acute care challenges [31], and these principles are equally applicable to aged care graduate nurse programs, informing best practices for programs in 2017.

Limitations

This study was conducted at a large tertiary referral hospital, potentially limiting generalizability to other settings. The PES-AUS modification (5-point Likert scale) means aggregate scores are not directly comparable to Middleton et al. [21]. Self-report measures may be subject to social desirability bias [32]. Despite these limitations, high participation rates and the mixed-methods design provide a comprehensive understanding of new graduate nurse experiences during transition.

Conclusion

Ensuring successful transition for new graduate nurses in demanding aged care settings is crucial for a safe and competent workforce. This study demonstrates that while transitional support programs are beneficial, qualitative data reveals ongoing unmet needs for clinical, social, and emotional support. Specifically, concerns about workload and skill mix at both baseline and follow-up indicate a need for interventions focused on effective skill mix to better support new graduates in aged care. Understanding new graduate nurses’ experiences and unmet needs during their first year is essential for nurse managers, educators, and nurses to enhance support, promote confidence, and ensure competent practice within their scope in aged care. For aged care graduate nurse programs in 2017 and beyond, these findings underscore the importance of ongoing program evaluation and refinement to best meet the needs of new nurses entering this critical sector of healthcare.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Ghada El Ayoubi for data collection assistance, Sandy Middleton for PES-AUS permission, and Dr. Edward White and Dr. Julie Winstanley for MCSS-26 permission.

Funding

This research received no specific funding.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

AINs Assistants in Nursing

CNEs Clinical nurse educators

MCSS-26 Manchester Clinical Supervision Scale

MET Medical Emergency Team

NGNs Newly graduated registered nurses

NUMs Nurse unit managers

PES-AUS Practice Environment Scale – Australia

RN Registered Nurse

SPSS Statistical Package for the Social Sciences

TSP Transitional Support Program

Authors’ contributions

RH: principal investigator, conception, design, data collection, analysis, manuscript writing. YS: study design, data analysis, manuscript writing. LR: data analysis, manuscript writing. BE: manuscript writing. WH: manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval from Western Sydney University and South Western Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committees (H10055, LNR/11/LPOOL/510). Written informed consent obtained from all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral on jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

[1] Reference 1 (From Original Article)

[2] Reference 2 (From Original Article)

[3] Reference 3 (From Original Article)

[4] Reference 4 (From Original Article)

[5] Reference 5 (From Original Article)

[6] Reference 6 (From Original Article)

[7] Reference 7 (From Original Article)

[8] Reference 8 (From Original Article)

[9] Reference 9 (From Original Article)

[10] Reference 10 (From Original Article)

[11] Reference 11 (From Original Article)

[12] Reference 12 (From Original Article)

[13] Reference 13 (From Original Article)

[14] Reference 14 (From Original Article)

[15] Reference 15 (From Original Article)

[16] Reference 16 (From Original Article)

[17] Reference 17 (From Original Article)

[18] Reference 18 (From Original Article)

[19] Reference 19 (From Original Article)

[20] Reference 20 (From Original Article)

[21] Reference 21 (From Original Article)

[22] Reference 22 (From Original Article)

[23] Reference 23 (From Original Article)

[24] Reference 24 (From Original Article)

[25] Reference 25 (From Original Article)

[26] Reference 26 (From Original Article)

[27] Reference 27 (From Original Article)

[28] Reference 28 (From Original Article)

[29] Reference 29 (From Original Article)

[30] Reference 30 (From Original Article)

[31] Reference 31 (From Original Article)

[32] Reference 32 (From Original Article)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.