Introduction

Critical care ultrasonography (US) has rapidly evolved into a vital tool for intensivists, fundamentally changing the evaluation and management of patients within the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) [1-5]. The integration of point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) has expanded diagnostic capabilities at the bedside, allowing for quicker and more informed clinical decision-making. Recognizing this paradigm shift, numerous training programs have emerged, focusing on various organ systems and clinical applications of critical care US [4-7]. However, a consensus on the specific skills and competencies expected of intensivists, particularly within neuro intensive care settings, has been historically lacking.

This gap in standardized training is especially pertinent in the United States, where neuro intensive care units manage complex patients with neurological injuries and illnesses. To address this, adapting established international guidelines and expert recommendations to the specific context of neuro ICU training programs in the USA is crucial. This article leverages the expert consensus previously established by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) to propose a framework for integrating essential “head-to-toe” ultrasonography skills into neuro intensive care unit training programs across the United States. The aim is to provide recommendations on the basic ultrasound skills that every neurointensivist graduating from US programs should possess for fundamental ultrasound evaluations of neuro ICU patients. These recommendations consider the diverse clinical scenarios encountered in a mixed general-neuro ICU, including both medical and surgical populations, excluding primarily cardiac and major non-cardiac surgery patients. This framework aims to enhance the competency of neurointensivists in the USA, ensuring they are well-versed in utilizing critical care ultrasound as a core skill in their practice.

Methods: Adapting International Consensus for US Neuro ICU Training Programs

The recommendations outlined in this article are adapted from an international expert consensus commissioned by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). This consensus involved a multidisciplinary panel of 19 intensivists from 10 countries, all recognized experts in critical care ultrasonography. These experts were divided into five subgroups, each focusing on specific areas of ultrasound competence: brain, heart, thoracic, abdominal, and vascular. A transversal subgroup was also dedicated to teaching and training methodologies within each domain.

The consensus was achieved using a Delphi method, a structured approach that employs web-based questionnaires to systematically gather and refine expert opinions. This iterative process aimed to minimize the heterogeneity of viewpoints and achieve the highest possible degree of convergence. Questions were transformed into actionable recommendations based on the level of agreement reached by the panel. Statements were categorized as strong recommendations (≥84% agreement), weak recommendations (≥74% agreement), and no recommendation (<74% agreement).

This article applies the findings of this robust international consensus to the specific needs of Neuro Intensive Care Unit Training Programs In The Usa. While the original consensus provides a broad overview of essential critical care ultrasound skills, this adaptation focuses on the implications and applications for training programs within the US healthcare system, emphasizing the importance of these skills for neurointensivists practicing in the USA.

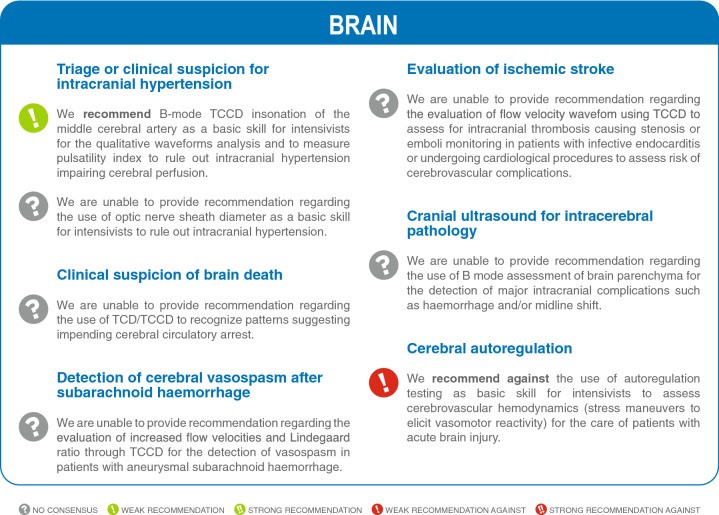

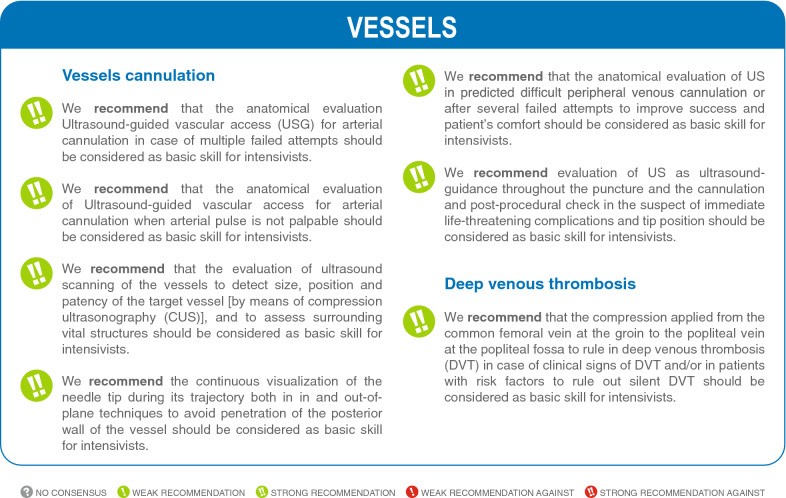

Fig. 5.

Summary of the Recommendations for Basic Critical Care Ultrasound Skills Relevant to Neuro ICU Training Programs in the USA.

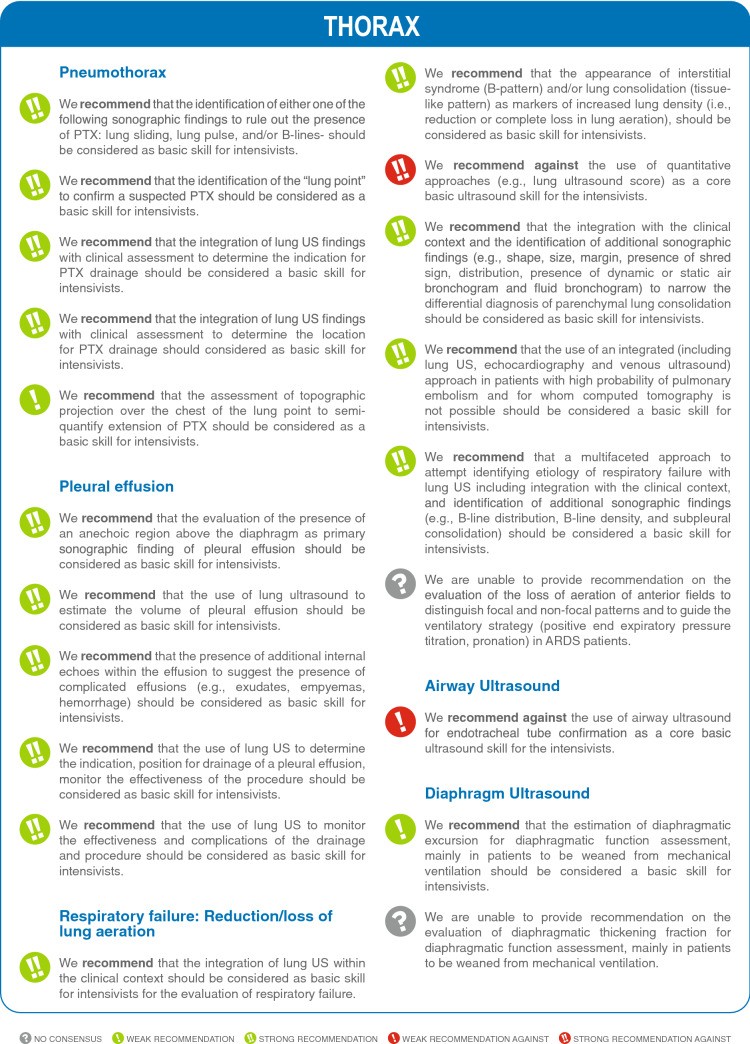

Continuation of Summary of Recommendations: Essential Lung Ultrasound Skills for US Neuro ICU Training.

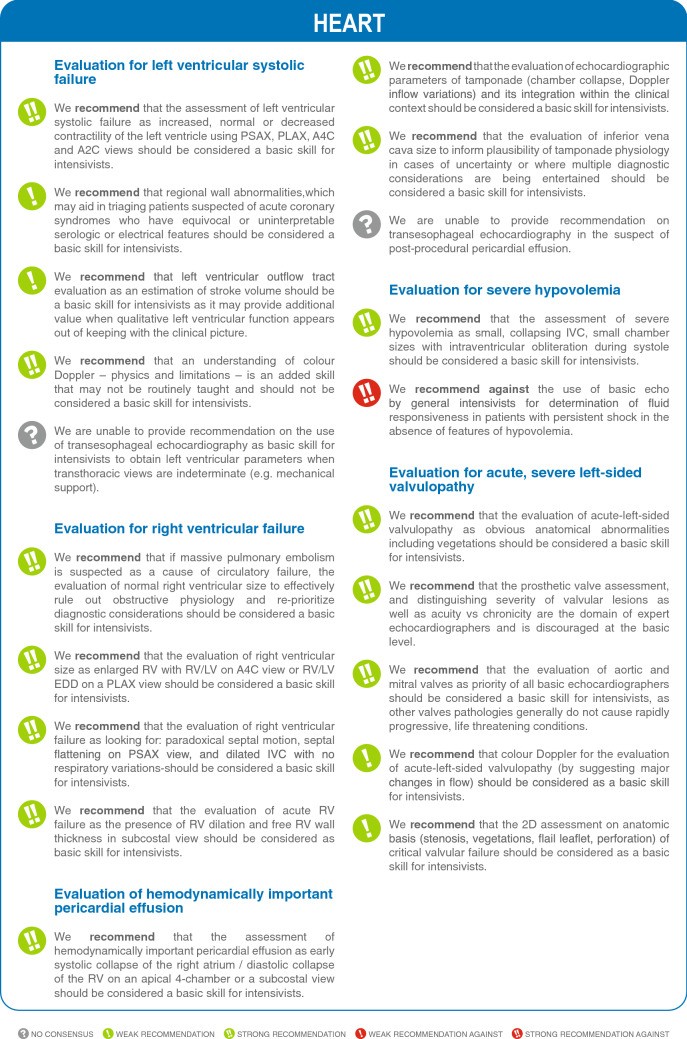

Cardiac Ultrasound Skills: A Key Component of Neuro ICU Ultrasound Training in the USA.

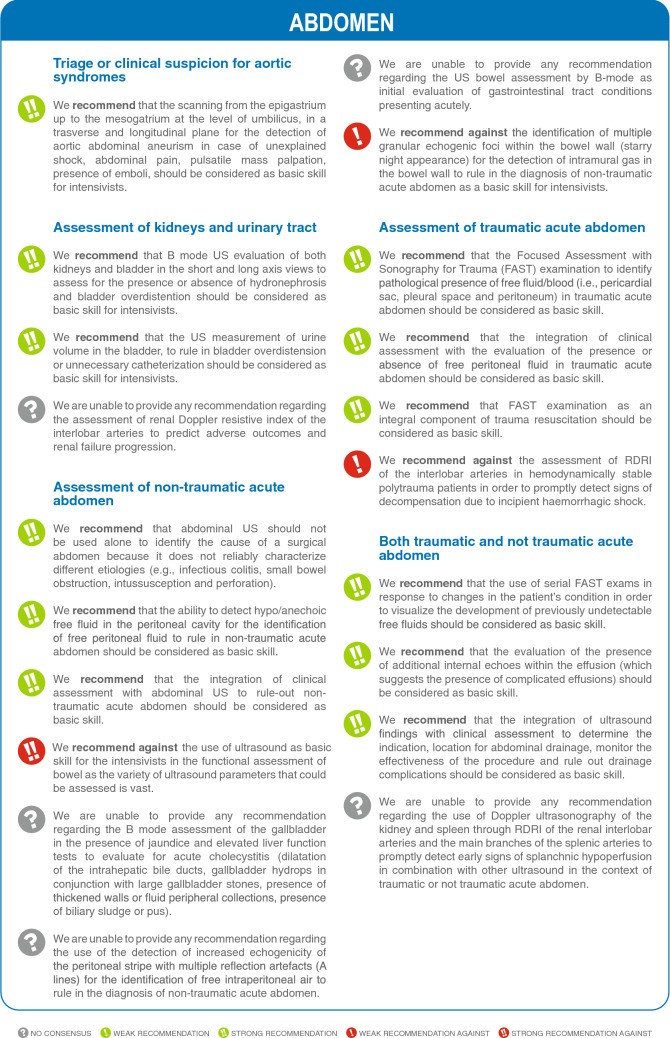

Abdominal Ultrasound Competencies for Neurointensivists in US Training Programs.

Vascular Ultrasound Skills: Essential for Neuro ICU Practice and Training in the USA.

Results: Core Ultrasound Skills for Neuro ICU Training in the USA

The expert consensus produced 74 statements across brain, lung, heart, abdomen, and vascular ultrasound domains. Of these, 49 statements (66.2%) received strong agreement, highlighting core skills considered fundamental. Eight statements (10.8%) received weak agreement in favor, while 3 (4.1%) received weak agreement against, and 14 cases (19.9%) did not achieve consensus, often due to the skills being deemed too advanced for basic competency. These results provide a structured framework for defining basic critical care ultrasound skills relevant to neuro intensive care unit training programs in the USA.

It is crucial to acknowledge that effective application of ultrasound in diverse clinical scenarios necessitates a foundational understanding of ultrasound physics, anatomy, and dedicated training in various ultrasound modalities. Furthermore, competence includes adhering to measurement standards, generating high-quality images, and accurately interpreting findings in clinical reports. Key limitations, parameters for assessment, crucial considerations, and training requirements for each domain are detailed in Tables 1 and 2 and Supplementary Tables S1-S4. Supplementary materials ESM2-ESM6 provide additional illustrative images and case descriptions for each organ system to further enhance understanding and training efficacy.

Table 1.

Summary of studies assessing training programs to reach competence in basic* CCUS

| Ultrasound modality/examined organs | Year, number of patients | Number of trainees/background | Novice in US | Didactic teaching/hands on | Number of examinations by trainee/study duration | Training using computarized simulation | Agreement with expert |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic TTE/heart | 2007 [16] 61 ICU patients | 4 residents/anesthesiology Medicine | Yes | 3 h/5 h | Mean: 15 (range: 11–20) 6 months | No | LV systolic dysfunction: 0.76 ± 0.09 (0.59–0.93)b LV dilatation: 0.66 ± 0.12 (0.43–0.90) RV dilatation: 0.71 ± 0.12 (0.46–0.95) Pericardial effusion: 0.68 ± 0.18 (0.33–1.03) |

| 2011 [17] 201 ICU patients | 6 residents/anesthesiology Medicine | Yes | 4 h/6 h 2 h cases | Mean: 33 (range: 29–38) 6 months | No | LV systolic function: 0.84 (0.76–0.92)b LV dilatation: 0.90 (0.80–1.0) RV dilatation: 0.76 (0.64–0.89) IVC dilatation: 0.79 (0.63–0.94) Respiratory variation of IVC size: 0.66 (0.43–0.89) Pericardial effusion: 0.79 (0.58–0.99) Tamponade: 1 (1–1) | |

| 2016 [18]a 223 ICU patients | 5 residents (program I) 6 residents (program II) Critical care | Yes | Program I: 1.5 h/2 h 1 h cases Program II: 1.5 h/3 h 2 h cases | Program I: Mean: 27 Program II: Mean: 26 12 months | No | Program I | Program II |

| LV systolic dysfunction | 0.75 (0.64–0.86) | 0.77 (0.66–0.88)b | |||||

| Heterogeneous LV contraction | 0.55 (0.38–0.72) | 0.49 (0.33–0.65) | |||||

| RV dilatation | 0.46 (0.27–0.65) | 0.67 (0.54–0.80) | |||||

| Pericardial effusion: | 0.83 (0.67–0.99) | 0.76 (0.60–0.93) | |||||

| Respiratory variation of IVC size | 0.53 (0.30–0.77) | 0.27 (0.09–0.45) | |||||

| Significant mitral regurgitation | 0.42 (0.01–0.84) | 0.64 (0.40–0.87) | |||||

| Significant aortic regurgitation | − 0.02 (− 0.04 to 0) | 1 | |||||

| 2020 [19]a 270 ICU/CCU patients | 7 residents Critical care | Yes | 38 h/30 tutored scans | Mean: 39 5 months | Yes | LV systolic dysfunction: 0.77 (0.65–0.89)b RV size: 0.76 (0.59–0.93) Pericardial effusion: 0.32 (0.09–0.56) IVC size: 0.56 (0.45–0.68) | |

| 2018 [15] 965 TTE including 256 TTE for skills assessment | 12 residents (intervention group) 12 residents (control group) Anesthesiology Medicine | Yes | Both groups: 4 h/6 h 2 h cases Simulation: 12 h | Intervention group: Mean: 35 ± 3 Control group: Mean: 39 ± 3 6 months | Intervention group: yes Control group: no | Skills assessment score (maximal: 54 points; intervention vs control group): Month 1: 41.5 ± 5.0 vs 32.3 ± 3.7 (p = 0.0004) Month 3: 45.8 ± 2.8 vs 42.3 ± 3.7 (p = 0.02) Month 4: 49.7 ± 1.2 vs 50.0 ± 2.7 (p = 0.64) Mean number of TTE for competency: 30 ± 9 vs 36 ± 7 (p = 0.01) LV systolic function and size, homogeneity of LV contraction, RV systolic function and size, pericardial effusion, IVC size, left-sided valvular regurgitation | |

| 2013 [21] | 18 residents Critical care | Yes (72%) | 8 h/15 h | 21 ± 20 | No (only for assessment of proficiency) | Skills assessment score (maximal: 40 points): mean 84% (range: 71–97%) LV systolic function (binary response), RV systolic function (binary response), pericardial effusion (binary response), volume status | |

| 2013 [20]a | 7 residents Critical care | Yes | 5 h/3 h | Mean: 15 (range: 5–31) 1 month | No | LV systolic function: 0.67b Regional wall motion abnormality: 0.49 Pericardial effusion: 0.60 Valvulopathy: 0.50–0.54 | |

| 2016 [22] 36 ICU patients | 6 residents Critical care | Yes | 8 h/8 h | 20 per trainee | No | Skills assessment score (maximal: 68 points): Efficiency score: from 1.55 (baseline) to 2.61 (after 20 examinations) LV systolic function and size, RV systolic function and size, pericardial effusion, IVC size | |

| 2005 [23] 90 ICU patients | 6 physicians Critical care | Yes | 10 h total | 9 months | No | Agreement with expert for interpretation: 84% LV systolic function and size, regional wall motion abnormality, pericardial effusion | |

| 2014 [24] 318 ICU patients | 7 fellows Critical care | No | 10 h/– | Median: 40 (range: 34–105) 12 months | No | Diagnosis capacity: predefined criteria for acceptability of the examination Average proportion of acceptable findings: 70% before 10 examinations to 92% after 30 examinations (p LV systolic function, severe acute core pulmonale, pericardial effusion, IVC size, mitral regurgitation | |

| 2017 [25] | 27 trainees (junior, senior, specialist) Critical care | Yes | –/4 h | 50 | Yes | Appropriate diagnostic interpretation in 56% of trainees, and therapeutic suggestion in 52% of the time (vs 100% in experts); a cut–off of 40 and 50 studies allowed appropriate diagnosis and management respectively, with a 100% specificity and 40% sensitivity LV function and size, RV function and size, pericardial effusion and tamponade, IVC size and collapsibility | |

| 2009 [26] 44 patients | – Critical care | Yes | 2 h/4 h | – | No | LV systolic function: 0.72 (0.52–0.93)b | |

| 2012 [27] | 100 medical practitioners Anesthesiology Critical care | Yes | 40 h tutorial/9 h | – | No | LV size: 91–100% of correct answers LV systolic function: 97–100% of correct answers RV size: 93–100% of correct answers RV systolic function: 90–100% of correct answers Haemodynamic state: 94–100% of correct answers Moderate-to-severe left–sided valvulopathy: 90 to 98% of correct answers Mild left-sided valvulopathy: 53–100% of correct answers | |

| 2014 [28] | 8 fellows Critical care | Yes | 6 h/6 h | – | No | Cardiac US: increase of mean knowledge assessment score from 58 to 86% (p = 0.05) after training; increase of mean bedside skills assessment from 0 to 79% after training (p | |

| 2017 [8] | 363 learners Critical care Various backgrounds | Yes | 3-day training course | – | No | RV size: mean recognition from 68% (pretest) to 98% after training; practical skills from 17% (pretest) to 85% after training | |

| 2014 [29] 48 patients | 16 residents Anesthesiology Medicine | Yes (n = 12) | 2 h/– | 67 6 months | No | LV systolic function, RV dilatation, pericardial effusion, IVC respiratory variations; agreement with expert (0: no; 1: yes): 0.8 ± 0.4 | |

| Abdominal US and lung | 2009 [30] 77 patients | 8 residents Critical care | Yes | 2.5/6 | (73 overall) | No | Pleural effusion**: 0.3 (0.01–0.62) Thoracentesis feasibility: 0.65 (0.32–0.97) Intraperitoneal effusion: 0.44 (0.1–0.9) Abdocentesis feasibility: 0.82 (0.49–1.15) Obstructive uropathy: 0.77 (0.34–1.2) Chronic renal disease: 1 (1–1) |

Studies on Competency in Basic Critical Care Ultrasound (CCUS) Training Programs.

Table 2.

Summary of current recommendations issued by scientific societies

| Ultrasound modality/examined organs | Year/source | Targeted trainees | Theoritical program | Number of examinations/tutored examinations | Computerized simulation | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basic TTE/heart | 2011 [1, 31–33] Critical care round table | Every ICU physician | ≥ 10 h (lectures, illustrative didactic cases with image-based training) | ≥ 30 fully supervised TTE examinations | – | Round table involving experts from 11 Critical Care Societies in 5 continents |

| Transcranial Doppler | American Academy of Neurology https://www.aan.com/siteassets/home–page/tools–and–resources/academic–neurologist––researchers/teaching–materials/aan–core–curricula–for–program–directorstor/neuroimage–fellow_tr.pdf | Neurocritical care, neuroimaging fellows No recommendations for general critical care | – | 100 performed and interpreted | – | – |

| Lung/Pleura | 2014 Canadian recommendations in anesthesia/CCUS | Anesthesia/critical care | – | 15 [34] to 20 [35] | – | – |

| FAST (Abdomen) | 2020 Canadian anesthesia recommendation: expert consensus | Anesthesia trainee | – | 20 [34] | – | – |

| Abdominal free fluid | 2014 Canadian recommendations in CCUS: expert consensus | Critical care | – | 10 [35] | – | – |

| Renal | 2014 Canadian recommendations in CCUS: expert consensus | Critical care | – | 25 [35] | – | – |

| Vascular | 2014 Canadian recommendations in CCUS | Critical care | – | 10 | – | – |

| Abdominal Aorta | 2014 Canadian recommendations in CCUS: expert consensus | Critical care | – | 25 [35] | – | – |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 2014 Canadian recommendations in CCUS: expert consensus | Critical care | – | 25 [35] | – | – |

| Vascular access | 2014 Canadian recommendations in CCUS: expert consensus | Critical care | – | 10 [35] | – | – |

| Each application | American College of Emergency Physicians https://www.acep.org/globalassets/new–pdfs/policy–statements/ultrasound–guidelines–––emergency–point–of–care–and–clinical–ultrasound–guidelines–in–medicine.pdf | Emergency medicine | – | 25 | – | – |

Current Guidelines for Critical Care Ultrasound Training Programs from Scientific Societies.

Brain Ultrasound Skills in US Neuro ICU Training Programs

Brain ultrasound holds significant promise in neurocritical care, offering non-invasive insights into intracranial dynamics. For US neuro ICU training programs, the following skills are pertinent:

Item 1. Triage of Intracranial Hypertension

- Recommendation: Integrate B-mode Transcranial color-coded duplex (TCCD) insonation of the middle cerebral artery as a basic skill for qualitative waveform analysis and pulsatility index measurement to rule out intracranial hypertension (ICH) that may impair cerebral perfusion (weak recommendation).

- Rationale: ICH is a frequent and critical complication of brain injury [8]. Non-invasive methods like TCCD can aid in ruling out ICH, offering advantages over invasive intracranial pressure monitoring, which is time-consuming and has potential contraindications [9, 10]. TCCD’s ability to visualize vessels enhances pulse Doppler gate placement. While Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter (ONSD) measurement is promising, the expert panel deemed it a more advanced skill, and thus, no recommendation was made for its inclusion as a basic skill in US neuro ICU training programs.

Fig. 1.

Brain ultrasound. A, B, D Images obtained using phased-array probe placed over the temporal window. Temporal windows are used for insonation of middle cerebral artery (MCA) anterior (ACA) and posterior cerebral artery (PCA). C Sub occipital windows can be performed for insonation of basilar (BA) and vertebral arteries (VA)

Temporal and Suboccipital Windows for Brain Ultrasonography in Neuro ICU Training.

Items 2-5. Advanced Brain Ultrasound Skills (No Recommendation for Basic US Neuro ICU Training)

The expert panel did not reach a consensus to recommend the following as basic skills for neuro ICU training programs in the USA:

- Item 2. Clinical suspicion of brain death: Using TCD/TCCD to recognize patterns suggestive of impending cerebral circulatory arrest.

- Item 3. Detection of cerebral vasospasm: Evaluating increased flow velocities and Lindegaard ratio for vasospasm detection post-subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- Item 4. Evaluation of ischemic stroke: Assessing flow velocity waveforms using TCCD for intracranial thrombosis or emboli monitoring.

- Item 5. Cranial ultrasound for intracerebral pathology: Using B-mode assessment for detecting major intracranial complications like hemorrhage or midline shift.

- Rationale: These skills, while valuable, were considered too specialized and advanced for basic competency within neuro ICU training programs. Brain death diagnosis and vasospasm monitoring often involve specialized neurointensive care physicians or neurologists using advanced imaging modalities. Similarly, stroke evaluation and detailed parenchymal assessment require advanced training beyond the scope of basic critical care ultrasound skills for neurointensivists in the USA.

Item 6. Cerebral Autoregulation

- Recommendation: Training programs in the USA should not include autoregulation testing as a basic skill for neurointensivists to assess cerebrovascular hemodynamics in acute brain injury patients (weak recommendation against).

- Rationale: While cerebral autoregulation assessment is important in managing brain-injured patients [9], the techniques (stress maneuvers to elicit vasomotor reactivity) were deemed too advanced for basic neuro ICU ultrasound training programs in the USA.

Thoracic Ultrasound Skills in US Neuro ICU Training Programs

Thoracic ultrasound is invaluable for diagnosing and managing respiratory complications in neuro ICU patients. US neuro ICU training programs in the USA should incorporate these core skills:

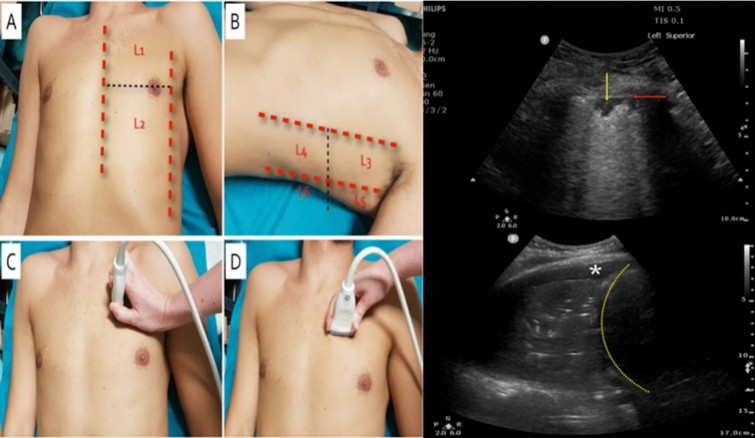

Fig. 2.

Lung ultrasound. Images obtained using low-frequency curvilinear probe placed with orientation marker directed cranially. Technique for a complete thoracic examination. Panels A–D: when acquiring lung ultrasound images, a structured approach includes proper patient position and exposure and appropriate scanning protocol. A six-area per hemithorax approach is usually considered for a complete thoracic assessment: anterior, lateral and posterior fields are identified by sternum, anterior and posterior axillary lines (red dotted lines). Right upper panel: consolidation with static air bronchogram. Lung ultrasound scan of a posterior-inferior field with a low-frequency phased-array transducer in longitudinal scan. Right lower panel: consolidation with dynamic linear-arborescent air bronchogram. Lung ultrasound scan of a posterior-inferior field with a low-frequency curvilinear transducer in longitudinal scan. The diaphragm is well visualized as one of the basic landmarks (yellow dotted arrow), thus allowing to correctly identify intra-thoracic and intra-abdominal structures. The lung presents complete loss of aeration: the lobe is visualized as a tissue-like pattern. Within the lung, multiple white images are visualized; they move synchronously with tidal ventilation and present a shape mimicking the anatomical airway: they correspond to dynamic linear-arborescent air bronchogram. This pattern suggests the main airway is patent and is highly specific for community-acquired or ventilator-associated pneumonia, depending on the context. A small pleural effusion is also visualized as a hyperechoic space surrounding the consolidated lung (*)

Lung Ultrasound Technique and Findings Essential for Neuro ICU Training in the USA.

Item 1. Pneumothorax (PTX)

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training programs should strongly emphasize:

- Identifying lung sliding, lung pulse, and/or B-lines to rule out pneumothorax.

- Identifying the “lung point” to confirm suspected pneumothorax.

- Integrating lung US findings with clinical assessments to guide pneumothorax drainage decisions and location.

- Assessing topographic projection of the lung point to semi-quantify pneumothorax extent (weak recommendation).

- Rationale: Lung US is highly accurate for pneumothorax detection, surpassing chest X-ray in sensitivity and comparable to CT scans [15, 16]. Integrating lung US into trauma protocols (eFAST) highlights its importance [17]. These skills are crucial for rapid diagnosis and management of pneumothorax in neuro ICU patients.

Item 2. Pleural Effusion

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training should strongly emphasize:

- Evaluating for anechoic regions above the diaphragm as a primary sign of pleural effusion.

- Using lung US to estimate pleural effusion volume.

- Recognizing internal echoes within effusions suggesting complicated effusions.

- Utilizing lung US to guide pleural effusion drainage indication and placement.

- Using lung US to monitor drainage effectiveness and complications.

- Rationale: Lung US is more sensitive than chest X-ray for detecting small pleural effusions and excels at differentiating effusions from consolidations [19]. It provides reliable volume estimation and guides safe drainage procedures [19-21].

Item 3. Respiratory Failure and Lung Aeration

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training programs should strongly emphasize:

- Integrating lung US within clinical context for respiratory failure evaluation.

- Recognizing interstitial syndrome (B-lines) and lung consolidation (tissue-like pattern) as markers of reduced lung aeration.

- Integrating additional sonographic findings (shape, size, air/fluid bronchograms) with clinical context for diagnosing parenchymal consolidation.

- Using integrated lung, cardiac, and venous ultrasound for suspected pulmonary embolism when CT is not feasible.

- Employing a multifaceted approach (B-line distribution, density, subpleural consolidation) to differentiate etiologies of respiratory failure (lung injury vs. cardiogenic edema).

- Recommendation Against: Quantitative lung ultrasound scoring should not be considered a basic skill (strong recommendation against).

- Rationale: Lung US enhances differential diagnosis of lung parenchymal diseases and guides management of acute respiratory failure [23]. Integrating ultrasound findings with clinical assessment improves diagnostic accuracy for respiratory failure and pulmonary embolism [22, 23]. Quantitative scoring, however, is not considered a basic skill for US neuro ICU training in the USA.

Item 4. Airway Ultrasound

- Recommendation Against: Airway ultrasound for endotracheal tube confirmation should not be a basic skill in US neuro ICU training (weak recommendation against).

- Rationale: While airway ultrasound has applications in airway management [26], the expert panel did not recommend it as a basic skill for endotracheal tube confirmation in US neuro ICU training programs, potentially due to limited evidence and the need for advanced training.

Item 5. Diaphragm Ultrasound

- Recommendation: Estimating diaphragmatic excursion for function assessment, particularly in weaning from mechanical ventilation, should be a basic skill (weak recommendation).

- Rationale: Diaphragmatic ultrasound is a feasible bedside tool for assessing diaphragm function, identifying paralysis, and predicting weaning outcomes [27-29]. Diaphragmatic excursion (DE) is recommended as a basic skill, while diaphragmatic thickening fraction (TF) was not endorsed due to technical challenges.

Cardiac Ultrasound Skills in US Neuro ICU Training Programs

Basic echocardiography is essential for hemodynamic assessment in neuro ICU patients. US neuro ICU training programs should incorporate these cardiac ultrasound skills:

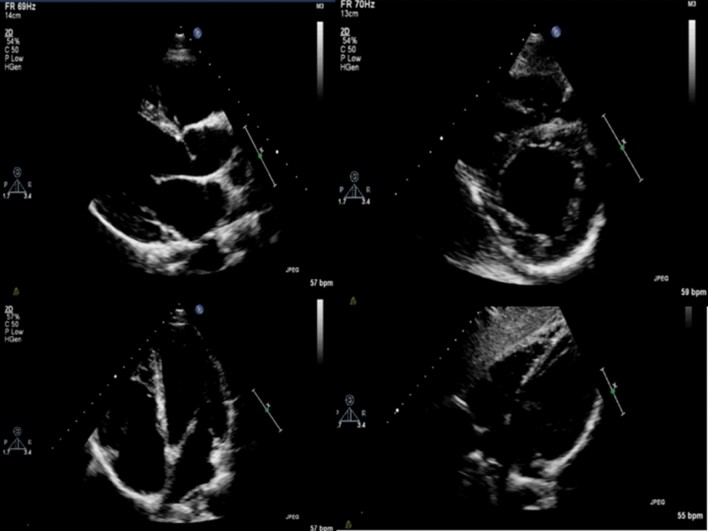

Fig. 3.

Standard cardiac views. The images were obtained using a standard phased-array probe. Upper left panel. Parasternal long axis, where probe placed in left parasternal areas, with orientation marker pointing to the patient’s right shoulder; Upper right panel. parasternal short-axis, where probed placed in left parasternal area with orientation marker pointing to patient’s left shoulder; Lower left panel. Apical four-chamber, where probe placed over the apex of the heart with orientation marker pointing to the patient’s left; Lower right panel. Subcostal four-chamber, where probe placed subxiphoid with orientation marker pointing to the patient’s left

Standard Cardiac Views for Basic Echocardiography Training in Neuro ICUs in the USA.

Item 1. Left Ventricular (LV) Systolic Failure

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training should strongly emphasize:

- Assessing LV systolic function (increased, normal, decreased contractility) using four standard views.

- Recognizing regional wall motion abnormalities to triage suspected acute coronary syndromes (weak recommendation).

- Evaluating LV outflow tract velocity time integral for stroke volume estimation (weak recommendation).

- Recommendation Against: Understanding color Doppler physics is valuable but should not be considered a basic skill (strong recommendation). Transesophageal echocardiography is not recommended as a basic skill.

- Rationale: Bedside LV systolic function assessment is crucial for cardiogenic shock evaluation [30]. Basic recognition of normal and abnormal LV findings is expected in undifferentiated shock. While transesophageal echocardiography has advantages, it’s considered an advanced skill.

Item 2. Right Ventricular (RV) Failure

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training programs should strongly emphasize:

- Evaluating normal RV size to rule out obstructive physiology in suspected massive pulmonary embolism.

- Assessing RV size (enlarged RV, RV/LV ratios) on apical four-chamber or parasternal long-axis views.

- Recognizing RV failure signs: paradoxical septal motion, septal flattening, and dilated IVC with minimal respiratory variation.

- Evaluating acute RV failure via free RV wall thickness in subcostal view combined with RV dilatation.

- Rationale: RV failure detection is vital for diagnosis, prognosis, and understanding heart-lung interactions in the ICU [32, 33]. Basic bedside RV assessment provides critical information for managing cardiopulmonary failure.

Item 3. Hemodynamically Important Pericardial Effusion

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training should strongly emphasize:

- Assessing for early systolic right atrial collapse/diastolic RV collapse on apical four-chamber or subcostal views as signs of hemodynamically significant pericardial effusion.

- Evaluating echocardiographic tamponade parameters (chamber collapse, Doppler inflow variations) and integrating with clinical context.

- Evaluating IVC size and dilation to assess tamponade plausibility.

- Recommendation Against: Transesophageal echocardiography is not recommended as a basic skill for post-procedural pericardial effusion suspicion.

- Rationale: Detecting or excluding pericardial effusion is a core skill, simplified by point-of-care echocardiography [34]. Pericardial assessment is recommended in undifferentiated shock or cardiac arrest. A non-dilated IVC often rules out tamponade.

Item 4. Severe Hypovolemia

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training should strongly emphasize:

- Recognizing severe hypovolemia signs: small, collapsing IVC and small chamber sizes with intraventricular obliteration during systole.

- Recommendation Against: Ultrasound for determining fluid responsiveness in persistent shock without hypovolemia features should not be a basic skill (strong recommendation).

- Rationale: Understanding echocardiographic features of hypovolemic shock is essential [35, 36]. Echocardiography’s role in hypovolemia is more relevant in occult or chronic cases.

Item 5. Acute, Severe Left-Sided Valvulopathy

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training should strongly emphasize:

- Evaluating for acute left-sided valvulopathy via obvious anatomical abnormalities like vegetations.

- Prioritizing aortic and mitral valve assessment as basic skills.

- For those proficient in color Doppler, its use for acute left-sided valvulopathy evaluation (flow changes) is a weak recommendation.

- 2D anatomical assessment (stenosis, vegetations, flail leaflet) of critical valvular failure is a weak recommendation.

- Recommendations Against: Prosthetic valve assessment and detailed valvular lesion severity assessment are not basic skills (strong recommendation).

- Rationale: Basic echocardiography can identify obvious mechanical failure of mitral or aortic valves, providing crucial diagnostic information. Cases with valvular disease features warrant focused mitral and aortic valve assessment [35]. Systematic recording of echo studies for expert discussion is recommended in uncertain cases.

Abdominal Ultrasound Skills in US Neuro ICU Training Programs

Abdominal ultrasound is increasingly relevant in neuro ICU for diagnosing various conditions. US neuro ICU training programs should incorporate these skills:

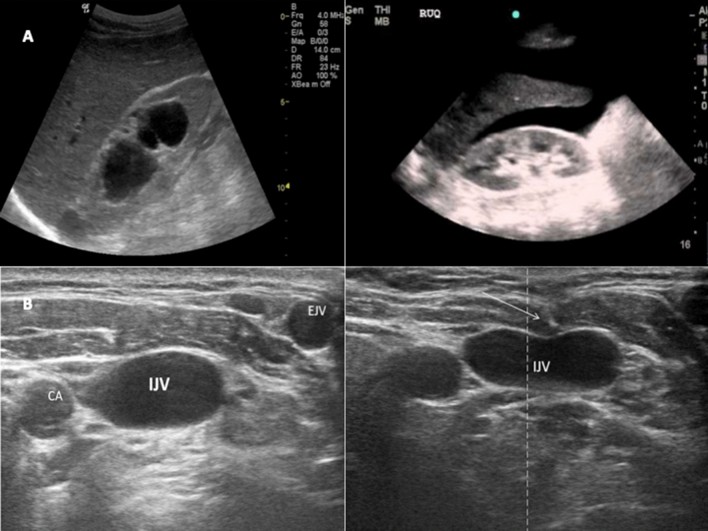

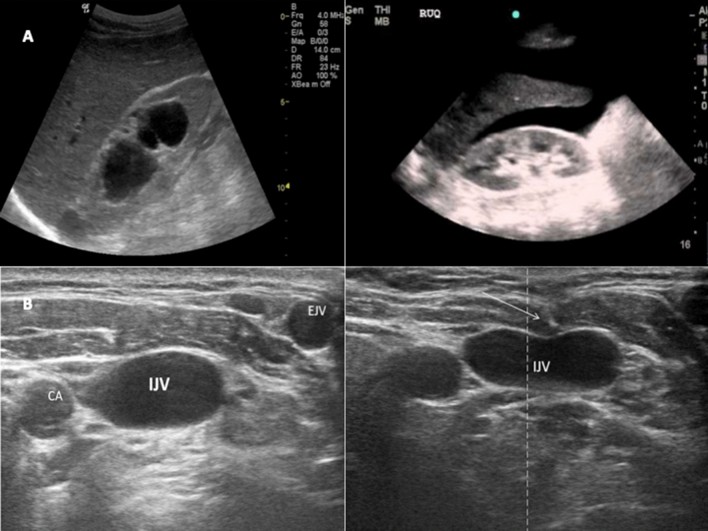

Fig. 4.

Panels A abdominal ultrasound: images obtained using low-frequency curvilinear probe placed over the right, subcostal area, mid-axillary line with orientation marker pointing cranially. Left: severe hydronephrosis of the right kidney. Right: free fluid in the hepatorenal recess. Panels B vascular ultrasound. Left: short-axis view of the right internal jugular vein (IJV), external jugular vein (EJV) and carotid artery (CA). Right: out-of-plane puncture of the internal jugular vein (IJV) the arrow shows the pressure on the anterior wall of the vein of the tip of the needle

Abdominal and Vascular Ultrasound Applications in Neuro ICU Training Programs in the USA.

Item 1. Aortic Syndromes

- Recommendation: Scanning from epigastrium to mesogastrium for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) detection in unexplained shock, abdominal pain, pulsatile mass, or emboli should be a basic skill (strong recommendation).

- Rationale: Bedside abdominal US is highly accurate for AAA detection [37]. Screening reduces aortic syndrome mortality [38]. AAA diagnosis via US is a basic skill, but rupture diagnosis is complex and requires clinical integration.

Item 2. Kidneys and Urinary Tract

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training should strongly emphasize:

- B-mode evaluation of kidneys and bladder for hydronephrosis and bladder overdistention.

- Qualitative urine volume assessment to identify overdistention or avoid unnecessary catheterization.

- Recommendation Against: Renal Doppler Resistive Index (RDRI) assessment is not recommended as a basic skill.

- Rationale: B-mode US is crucial for hydronephrosis and kidney injury diagnosis [39]. RDRI, while promising for AKI prediction [40, 41], requires further validation for basic use.

Item 3a. Acute Abdomen (Traumatic and Non-Traumatic)

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training should strongly emphasize:

- Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST) examination for free fluid/blood in traumatic acute abdomen.

- Integrating clinical assessment with free peritoneal fluid evaluation in traumatic acute abdomen.

- FAST examination as part of trauma resuscitation.

- Detecting hypo/anechoic free fluid to rule in non-traumatic acute abdomen.

- Integrating clinical assessment with abdominal US to rule out non-traumatic acute abdomen.

- Serial FAST exams to visualize developing free fluids.

- Evaluating internal echoes within effusions for complicated effusions.

- Integrating ultrasound findings with clinical context to guide abdominal drainage and monitor procedures.

- Recommendations Against:

- Abdominal US alone should not be used to identify the cause of surgical abdomen.

- Ultrasound is not recommended as a basic skill for functional bowel assessment.

- RDRI assessment in stable polytrauma patients to detect decompensation is not recommended as a basic skill (weak recommendation).

- Identifying “starry night appearance” for intramural gas detection is not a basic skill (weak recommendation against).

- No Recommendation: B-mode gallbladder assessment for cholecystitis, intraperitoneal air detection, and bowel assessment for acute GI conditions are not recommended as basic skills.

- Rationale: FAST is crucial in trauma and shock evaluation [42]. Abdominal US is fundamental for FAST, detecting peritoneal fluid, and guiding paracentesis [43, 44]. However, advanced skills like intramural gas detection and functional bowel assessment are not considered basic for US neuro ICU training programs in the USA.

Vascular Ultrasound Skills in US Neuro ICU Training Programs

Vascular ultrasound is indispensable for access and DVT assessment in neuro ICU. US neuro ICU training programs should include these vascular ultrasound skills:

Fig. 4.

Panels A abdominal ultrasound: images obtained using low-frequency curvilinear probe placed over the right, subcostal area, mid-axillary line with orientation marker pointing cranially. Left: severe hydronephrosis of the right kidney. Right: free fluid in the hepatorenal recess. Panels B vascular ultrasound. Left: short-axis view of the right internal jugular vein (IJV), external jugular vein (EJV) and carotid artery (CA). Right: out-of-plane puncture of the internal jugular vein (IJV) the arrow shows the pressure on the anterior wall of the vein of the tip of the needle

Vascular Access and DVT Assessment Skills for Neuro ICU Training in the USA.

Item 1. Vascular Cannulation

- Recommendations: US neuro ICU training should strongly emphasize:

- Anatomical ultrasound guidance (USG) for arterial cannulation in failed attempts or non-palpable pulses.

- Scanning vessels (peripheral and central veins) to assess size, position, patency (compression US), and surrounding structures.

- Continuous needle tip visualization during USG vascular access using in-plane and out-of-plane techniques.

- USG for difficult peripheral venous cannulation or after failed attempts.

- USG throughout cannulation, including puncture and post-procedural tip position checks.

- Rationale: USG vascular access enhances safety and efficiency compared to landmark-based methods [45]. USG in various settings is a basic skill for vascular cannulation [46, 47].

Item 2. Deep Venous Thrombosis (DVT)

- Recommendation: Compression ultrasound from common femoral to popliteal vein to rule in DVT in suspected cases or high-risk patients should be a basic skill (strong recommendation).

- Rationale: DVT risk factors are prevalent in ICU patients [45-48]. Compression technique is accurate for proximal lower extremity DVT diagnosis by intensivists [49-51].

Discussion and Conclusion: Advancing Neuro ICU Training Programs in the USA with Ultrasound Competency

This consensus-based framework provides essential guidance for integrating basic ultrasound skills into neuro intensive care unit training programs in the USA. These recommendations are intended to guide program directors and educators in developing curricula that equip neurointensivists with fundamental ultrasound competencies. It is vital to emphasize that this framework is not a rigid medico-legal standard but rather a dynamic guide for enhancing training and promoting competency in critical care ultrasound within neuro ICUs. Endorsement by professional societies in the USA, such as the Neurocritical Care Society and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, would further strengthen its adoption and impact.

The primary limitation of this framework, adapted from an international consensus, is the absence of a systematic literature review and evidence grading. However, the expert panel’s extensive experience and knowledge of critical care ultrasound literature ensure the recommendations are grounded in practical expertise. While potential biases exist in expert selection and voting, the diverse panel, with both general and specialized ultrasound expertise, aimed to balance high-quality recommendations with the practical needs of general intensivists, reflecting a consensus rather than individual opinions.

This framework covers a broad spectrum of ultrasound applications relevant to neuro ICU. However, limitations in scope meant some topics and clinical scenarios, like pulmonary pressure evaluation or cardiac surgery contexts, were not extensively addressed. Similarly, detailed methodological specifics and thresholds for each skill are not fully elaborated in this manuscript but are supplemented by extensive Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM), including videos and figures, to enhance practical understanding and training resources.

Moving forward, it is imperative that future research and training initiatives prioritize the effective implementation of “head-to-toe” ultrasonography within neuro ICUs in the USA. Further research should focus on validating the impact of these recommended skills on patient outcomes and optimizing training methodologies within neuro ICU fellowship programs. Curriculum development should incorporate didactic teaching, hands-on training, simulation, and competency assessments to ensure graduating neurointensivists are proficient in these essential ultrasound skills, ultimately improving patient care in neurocritical care settings across the United States.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material:

134_2021_6486_MOESM1_ESM.docx (Supplementary file 1)

134_2021_6486_MOESM2_ESM.docx (Supplementary file 2)

134_2021_6486_MOESM3_ESM.docx (Supplementary file 3)

134_2021_6486_MOESM4_ESM.docx (Supplementary file 4)

134_2021_6486_MOESM5_ESM.docx (Supplementary file 5)

134_2021_6486_MOESM6_ESM.docx (Supplementary file 6)

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine task force for critical care ultrasonography and ESICM for their support in developing this manuscript.

Abbreviations

A2C Apical two-chamber view

A4C Apical four-chamber view

AAA Abdominal aortic aneurysm

ARDS Acute respiratory distress syndrome

CCUS Critical Care Ultrasound

CUS Compression ultrasonography

DE Diaphragmatic Excursion

DVT Deep vein thrombosis

EDA End diastolic surface area

EDD End diastolic diameter

ESICM European Society of Intensive Care Medicine

FAST Focused assessment with sonography in trauma

ICH Intracranial Hypertension

ICU Intensive care unit

IVC Inferior vena cava

LV Left ventricle

ONSD Optic Nerve Sheath Diameter

PLAX Parasternal long-axis view

POCUS Point-of-Care Ultrasound

PSAX Parasternal short-axis view

PTX Pneumothorax

RDRI Renal Doppler Resistive Index

RV Right ventricle

TCCD Transcranial color Doppler

TCD Transcranial Doppler

TF Thickening Fraction

TTE Transthoracic Echocardiography

US Ultrasound

USG Ultrasound Guidance

Author contributions

CR and AVB designed and coordinated the consensus. CR drafted the manuscript, and AVB supervised. DP performed statistical analysis. AW edited and coordinated videos/images. All authors contributed to study conception, data analysis, manuscript revision, and final approval.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

AW, SM, ML, AM, AS, FST, and AVB report potential conflicts as detailed in the original manuscript. All other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral regarding jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chiara Robba, Email: [email protected].

The European Society of Intensive Care Medicine task force for critical care ultrasonography*, Email: [email protected].

The European Society of Intensive Care Medicine task force for critical care ultrasonography*: Chiara Robba, Adrian Wong, Daniele Poole, Ashraf Al Tayar, Robert T Arntfield, Michelle S Chew, Francesco Corradi, Ghislaine Douflé, Alberto Goffi, Massimo Lamperti, Paul Mayo, Antonio Messina, Silvia Mongodi, Mangala Narasimhan, Corina Puppo, Aarti Sarwal, Michel Slama, Fabio S Taccone, Philippe Vignon, and Antoine Vieillard-Baron