Introduction

In healthcare, particularly within the United States, financial models often clash with patient-centered care philosophies. Dr. Donald Berwick’s “Escape Fire” speech highlighted this critical misalignment, emphasizing the need for healthcare solutions that are not only scientifically sound and patient-focused but also financially viable and supportive of caregivers. Palliative care (PC), with its inherent “less is more” approach, perfectly exemplifies this challenge. While the clinical and ethical imperatives for palliative care are clear, widespread adoption hinges on demonstrating its financial sustainability and value to healthcare organizations, insurers, and policymakers.

For years, palliative care advocates have faced an uphill battle in securing consistent support and funding for their programs. The disconnect between clinical benefits and perceived financial burdens has often hindered the growth and integration of specialist palliative care services. A national survey of cancer centers underscored this, identifying financial concerns as the most significant obstacle to palliative care program implementation. To truly advance palliative care, we must bridge this gap and articulate a robust business case that resonates with all stakeholders.

The Clinical-Financial Divide in Healthcare

The root of this misalignment lies in the predominant fee-for-service (FFS) model that underpins the U.S. healthcare system. This model incentivizes volume – the more services provided, the greater the revenue. Conversely, palliative care prioritizes patient well-being and care alignment with individual goals, often leading to reduced utilization of high-cost services like hospitalizations and emergency room visits, while emphasizing more cost-effective alternatives such as home-based care.

Hospice care navigates this conflict through a distinct benefit structure, separating palliative care for the terminally ill from ongoing disease-directed treatments. However, for specialist palliative care outside of hospice, the business case is more nuanced. Palliative care needs to be integrated alongside curative treatments, not as an alternative, making the financial justification more complex.

Hospitals, deeply embedded in the FFS model, may perceive a financial disincentive in reducing hospital-based services. The Sutter Health Advanced Illness Management Program, despite its success in increasing hospice utilization and reducing hospitalizations, illustrates this dilemma. Program leaders acknowledged that while the intervention improved care and lowered overall costs, the FFS reimbursement structure penalized hospitals for reduced hospital stays, as these services like care coordination were not directly reimbursed.

This article aims to clarify how the clinical and ethical imperatives of palliative care are, in fact, intrinsically linked to positive financial outcomes. By drawing on published research and over 15 years of experience assisting palliative care programs, we present 10 core principles that form a compelling business model for specialist palliative care teams. These principles highlight the economic rationale for providing an extra layer of support for patients and families facing serious, life-limiting illnesses, especially in the context of evolving value-based payment models that are gradually replacing the traditional FFS system.

10 Pillars of a Palliative Care Program Business Plan

Principle 1: Addressing Unmet Needs and Reducing Suffering

The Clinical Imperative: Individuals facing serious, progressive illnesses and their families are highly vulnerable to multifaceted suffering, encompassing physical, emotional, and spiritual dimensions. Palliative care is fundamentally designed to proactively address and alleviate this suffering.

The business case for specialist palliative care (SPC) must begin with a robust clinical foundation. Without a clear clinical need, there is no basis for a financial model. It’s important to remember that the establishment of the Medicare Hospice Benefit followed the grassroots movement and foundational work of the first hospices in the U.S. by several years. The evidence is overwhelming: patients with serious illnesses and their families experience significant suffering. Equally compelling is the evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of SPC services in mitigating and preventing this suffering, improving quality of life, and enhancing the overall care experience.

Principle 2: Mitigating Avoidable High-Cost Healthcare Utilization

Reducing Unnecessary Burdens: Patients with progressive, life-limiting conditions often experience high utilization of expensive healthcare services, such as emergency department (ED) visits and repeated, extended hospital admissions. A significant portion of this utilization is often avoidable with proactive and coordinated care. These patterns are frequently observed in the final months of life but can emerge much earlier in the disease trajectory.

The extensive literature on healthcare utilization patterns for seriously ill patients consistently highlights areas for potential cost savings through better care management. For example, a recent study revealed that approximately half of older adults in the U.S. visit an ED in their last month of life. Of those, a staggering 75% are hospitalized, and over two-thirds of those hospitalized individuals ultimately die in the hospital setting. Furthermore, data indicates an increasing trend in intensive care unit (ICU) utilization for Medicare patients in their last month of life, and alarmingly, over 25% of patients receiving hospice care enroll within three days of death.

This high utilization of acute hospital services at the end of life would be justifiable if it aligned with patient and family preferences. However, numerous studies consistently demonstrate a mismatch. The proportion of individuals dying in hospitals and nursing homes far exceeds the percentage who express a preference for these locations. Globally, over 80% of people express a desire to die at home, underscoring the need for care models that support this preference and reduce reliance on costly institutional care when it is not desired or necessary.

Principle 3: Addressing the Financial Strain of End-of-Life Hospitalizations

Improving Hospital Financial Performance: Hospitalizations nearing the end of life tend to be prolonged and resource-intensive, resulting in substantial costs. This can lead to negative financial outcomes for both hospitals and payers, irrespective of whether they operate under fee-for-service or risk-based reimbursement models.

Numerous studies have documented the considerable duration and expense associated with hospitalizations near the end of life, directly impacting payer expenditures. However, examining payer costs or hospital costs in isolation doesn’t fully reveal the financial implications for hospitals. It’s crucial to understand the balance between hospital costs and payer reimbursements – are hospitals breaking even, generating a profit, or incurring a loss? This net margin data is often not publicly available but is essential for a complete financial picture.

To illustrate the magnitude of financial risk for both payers and providers, data from the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Health System provides valuable insight. Figure 1 compares hospital costs and reimbursements for three groups of Medicare beneficiaries: those who died in the hospital, those with serious illness and high mortality risk, and all other admissions.

Fig. 1. Medicare Inpatient Admissions at VCU Hospital – Fiscal Year 2011

Medicare inpatient admissions at Virginia Commonwealth University hospital in Fiscal Year 2011, stratified by disposition at discharge: deaths, survivors with high risk of mortality, and all others. aHigh-risk survivors defined as discharged to hospice or those with all patient refined—diagnosis-related group risk of mortality score of 4 combined with severity of illness score of 3 or 4. bNet margin represents revenues less total costs.

The data reveals that while reimbursement for the “deaths” and “high-risk survivors” groups is significantly higher (approximately three times greater) than the “all other” group, representing a substantial burden on Medicare, it still falls short of the actual costs incurred by the hospital. The net loss for Medicare hospitalizations at VCU in that year was primarily driven by the 16% of cases involving patients who died or were at high risk of death – a patient population highly relevant to palliative care.

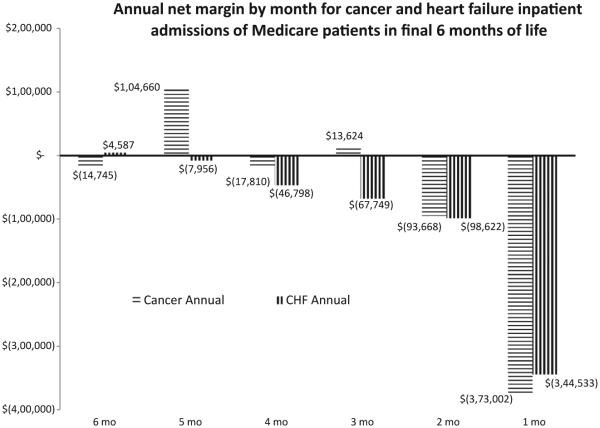

Further analysis of VCU data in Figure 2 demonstrates the declining net margin for cancer and congestive heart failure (CHF) admissions in the six months preceding death. This trend indicates that the FFS reimbursement model for inpatient care does not guarantee profitability, particularly for end-of-life care. Under Medicare’s inpatient prospective payment system (IPPS), and similar systems used by other payers, reimbursement is predetermined based on DRG classifications. While a hospital may achieve a positive net margin within a DRG if its costs are low, a negative margin occurs if costs exceed the fixed payment.

Fig. 2. Net Margin for End-of-Life Hospitalizations at VCU Hospital – Fiscal Years 2010-2012

Virginia Commonwealth University hospital data Fiscal Year 2010 to Fiscal Year 2012. X-axis is the month before death, ascertained from inpatient deaths and by querying data from the Social Security Death Master File to identify patients who died in other settings. The Y-axis is the net margin for this hospital (reimbursement minus total costs). CHF = congestive heart failure.

Hospitals may be unaware of the extent to which end-of-life care contributes to financial losses. Many hospitals primarily conduct financial analyses by broad disease categories (e.g., cancer, cardiology) rather than by disease trajectory. As value-based care models and shared savings programs become more prevalent, financial analytics must adopt a population health management perspective to accurately assess the financial impact of end-of-life care.

Analyses like these reveal potentially underestimated financial risks associated with the unprofitability of hospitalizations near the end of life. While some hospitals might focus on contribution margin (reimbursement minus direct costs), the underlying principle remains consistent: lengthy, resource-intensive admissions toward the end of life may not generate the positive net margins seen in other types of hospital admissions. Further research is warranted to comprehensively examine the net margin for end-of-life hospitalizations, considering both hospital costs and payer expenditures.

Principle 4: Reducing Penalties and Improving Quality Metrics

Mitigating Financial Penalties: Hospitals now face financial penalties from payers, particularly the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), for high 30-day readmission rates, 30-day mortality rates, and similar quality measures. A significant proportion of these metrics are influenced by care provided at the end of life.

CMS is driving a major shift in healthcare reimbursement by penalizing hospitals for avoidable readmissions and poor quality outcomes, including high 30-day mortality rates. The Readmission Reduction Program penalizes hospitals for excessive readmission rates within 30 days of initial hospitalization for specific conditions. Penalties, which began at up to 1% of DRG payments in FFY 2013, have escalated to a maximum of 3% for FFY 2015 and beyond, impacting all Medicare hospitalizations for a given hospital, not just the targeted conditions. In 2014, over 2,600 hospitals faced penalties, with 39 receiving the maximum 3% reduction. Maryland, the last state without DRG-based Medicare payments, now operates under a fixed annual hospital budget, effectively creating the same disincentive for excess hospitalizations.

The Value-Based Purchasing Program further incentivizes quality by adjusting payments to acute-care hospitals based on performance metrics, with potential adjustments up to 2.0% by FFY 2017. Hospital scores are based on process measures, outcome measures (including 30-day mortality for specific conditions), and patient experience. Outcome measures now constitute 40% of the total score. Like the Readmission Reduction Program, Value-Based Purchasing impacts all acute care Medicare payments.

From a hospital financial perspective, a single end-of-life hospitalization can trigger multiple negative consequences: negative net margin, readmission risk, and increased 30-day mortality rates. These factors combine to create significant financial and quality performance pressures.

CMS, as the largest payer in the U.S., is leading the transition from volume-based to value-based payment models. CMS has announced a goal to tie 50% of Medicare payments to quality or value by the end of 2018 through alternative payment models and value-based payments. This shift creates a stronger alignment between clinical and financial objectives, presenting a significant opportunity for palliative care. While some current CMS metrics may focus on acute conditions where palliative care is less directly involved (e.g., acute myocardial infarction), palliative care has consistently been associated with improved quality and reduced overutilization of certain healthcare services.

Quality measures endorsed by organizations like the National Quality Forum for cancer end-of-life care explicitly link quality with reduced overutilization of hospitalizations, ICU stays, and ED visits, and increased utilization of hospice and palliative care. Payers’ increasing focus on overutilization metrics provides a clear pathway for palliative care to demonstrate its value. By providing better outpatient and home-based care, palliative care programs can potentially avoid many of the hospital admissions and readmissions that negatively impact quality metrics and trigger penalties. This reframes the interpretation of 30-day mortality measures. High 30-day mortality for CHF admissions might not reflect poor inpatient CHF care but could indicate deficiencies in ambulatory CHF management or inadequate access to early palliative care.

Principle 5: The Value of Community-Based Palliative Care (CBPC)

Extending Care Beyond the Hospital: Community-based palliative care (CBPC) plays a crucial role in improving symptom management, coordinating care, and reducing ED visits and hospitalizations in the months leading up to death.

Hospice care is often initiated very late in the illness trajectory, close to the time of death, and inpatient palliative care is reactive, only accessible once a patient is already hospitalized. This leaves a significant gap in care for patients in the weeks and months before death, outside of the inpatient setting. CBPC is designed to fill this gap. Evidence consistently shows that CBPC reduces hospital utilization while simultaneously improving patient-reported outcomes such as symptom control, reduced distress, and increased satisfaction with care. The dramatic growth and interest in CBPC in recent years is fueled by the recognition that inpatient palliative care alone is insufficient and by compelling evidence from randomized controlled trials demonstrating the effectiveness of both home-based and outpatient clinic-based palliative care models. The financial implications of CBPC are further explored in Principle 9.

Principle 6: The Impact of Inpatient Palliative Care

Improving Inpatient Care Efficiency: Inpatient palliative care services enhance symptom management, improve care coordination, and reduce the overall cost of hospital admissions.

Numerous studies provide robust evidence that inpatient palliative care consultation services and dedicated units improve symptom control and reduce hospital costs. These cost reductions are observed in the days following palliative care consultation and are not limited to patients who die during hospitalization. Understanding the business case for inpatient palliative care necessitates clarifying whose costs are being saved. Are hospital cost savings passed on to payers? Often, the answer is no, due to payer mix, inpatient reimbursement structures, and the timing of palliative care intervention within a hospitalization.

Consider a scenario where a patient is admitted to the ICU via the ED and remains there for eight days before a palliative care consultation is requested. While palliative care intervention may reduce costs in subsequent days, it cannot retroactively alter costs incurred during the initial eight days of intensive care. The patient’s diagnosis and initial utilization patterns (Days 1-8) are likely to determine the DRG assignment and, consequently, the reimbursement amount. This predetermined reimbursement is unlikely to be changed by palliative care intervention initiated on Day 8.

If palliative care intervention leads to goal clarification and a shift in the treatment plan, allowing the patient to transfer from the ICU to a less resource-intensive unit, the hospital realizes tangible cost savings because the reimbursement is already fixed, regardless of actual costs. Conversely, in an FFS system using DRG-based payments, these cost savings are not directly passed on to payers, as their expenditure was prospectively determined and not linked to the specific services rendered after palliative care involvement.

There is some evidence that inpatient palliative care indirectly influences post-discharge utilization by increasing access to CBPC or hospice, which would reduce payer costs over time. Similarly, earlier palliative care involvement in a hospitalization could potentially influence treatment decisions and subsequent DRG assignments, impacting payer expenditures. However, overall, the financial incentive to invest in inpatient palliative care is stronger for hospitals than for payers under traditional FFS models.

Principle 7: Addressing Revenue Shortfalls in Palliative Care

Securing Financial Sustainability: In the traditional FFS model, third-party revenue generated by palliative care services typically covers only a portion of the total cost of a multidisciplinary palliative care team. Therefore, subsidies or innovative contractual agreements are essential to ensure program financial viability.

While services for patients with progressive illnesses often generate substantial clinical revenues (e.g., chemotherapy for cancer, cardiac surgery), palliative care service revenues are comparatively modest. CMS and most commercial insurers do not offer supplemental payments or specialized benefit packages specifically for palliative care. Specialist physicians can bill for evaluation and management visits, but these reimbursements are generally insufficient to cover the comprehensive costs of a multidisciplinary team, including salaries and benefits for all team members. This revenue inadequacy applies to both inpatient and community-based palliative care services. Furthermore, core palliative care team members, such as registered nurses, hospital-based social workers, and chaplains, often cannot bill third parties directly despite their critical roles in interdisciplinary palliative care delivery.

The financial challenge can be compounded by inefficient billing practices and the increasing competitive pressures on salaries for palliative care specialists. Consequently, specialist palliative care programs often require funding sources beyond traditional clinical revenue to cover the full costs of their interdisciplinary teams.

It is crucial for palliative care programs to accurately assess and articulate the cost of delivering care, as well as the direct cost savings and broader financial contributions they generate. A thorough understanding of both program costs and the full spectrum of expected benefits is a prerequisite for securing institutional support from a health system or negotiating service contracts with payers. Tools and resources are available to assist organizations in estimating their costs and benefits associated with palliative care programs.

Principle 8: Demonstrating Return on Investment for Inpatient Palliative Care

Hospitals Benefit from Inpatient PC: For hospitals, the combined value of reduced costs and improved operational efficiency resulting from inpatient palliative care almost invariably exceeds the cost of staffing the service, resulting in a positive return on investment (ROI). This holds true in both FFS and risk-based reimbursement environments.

Because inpatient palliative care demonstrably reduces costs within case-rate payment systems (as highlighted in Principles 3 and 6), and because these cost reductions are relatively easily measured and attributed to palliative care involvement, inpatient palliative care programs can readily demonstrate a positive ROI. Cost savings generated by palliative care often outweigh the subsidies needed to support the multidisciplinary team. For example, a study by Morrison et al. estimated a financial impact more than four times greater than the personnel investment. Similar analyses at VCU have shown an ROI exceeding five times the program investment. Calculating ROI requires quantifying two key elements: cost savings attributable to palliative care intervention and the portion of the annual palliative care program budget not covered by direct third-party reimbursement.

Principle 9: Return on Investment for Community-Based Palliative Care (CBPC)

Aligning Incentives for CBPC Success: The return on investment for CBPC is contingent on the degree to which financial and quality incentives are aligned within a given healthcare system. Entities bearing risk for high-cost end-of-life care have the strongest financial incentive to invest in CBPC.

While ROI analysis for inpatient palliative care is relatively straightforward, assessing CBPC ROI is more complex. As Principle 5 highlighted, early palliative care engagement can prevent hospitalizations by providing proactive symptom management and care coordination. From a payer perspective, these avoided hospitalizations translate into real and potentially significant cost savings. This realization has driven numerous payer-provider partnerships aimed at expanding CBPC delivery.

Why would a health system or hospital invest in CBPC? One compelling scenario is when a hospital recognizes that its current approach to end-of-life care is resulting in negative net margins and penalties related to readmissions and 30-day mortality. Even within a traditional FFS context, the clinical and financial incentives for CBPC can become aligned. This alignment is even stronger for hospitals participating in alternative payment models, such as health maintenance organizations (HMOs), shared savings programs, and accountable care organizations (ACOs), which directly reward minimizing overutilization of high-cost services. Indeed, the impetus to overcome barriers to CBPC can originate from both payers, seeking to control expenditures, and providers, aiming to improve care and financial performance under evolving payment models.

While the primary aim of CBPC is to proactively manage symptoms, prevent and alleviate distress, and enhance care coordination, demonstrating alignment with an organization’s financial interests is crucial for securing programmatic support – budgetary, political, and operational. This necessitates quantifying both the costs and revenues associated with reducing certain forms of healthcare utilization (e.g., hospitalizations) and the potential increases in costs and revenues associated with expanding other forms of care (e.g., CBPC, home health, hospice). Additionally, it’s important to factor in reductions in penalties related to overutilization (e.g., 30-day mortality) and, where applicable, financial rewards from more efficient care under risk-bearing contracts or ACO participation.

Healthcare reimbursement is constantly evolving. As payer-provider relationships continue to adapt and reshape, new models for shared savings and risk-sharing will emerge, creating incentives for bending the healthcare cost curve while maintaining and improving quality and patient-centered outcomes. Understanding the role of CBPC in this evolving landscape and continuously quantifying its projected and actual impacts is not a one-time task but an ongoing process.

Principle 10: Universal Applicability of Palliative Care Business Principles

Palliative Care Benefits All Healthcare Organizations: All types of healthcare organizations, regardless of size or setting, can evaluate the opportunities and impact of palliative care implementation using these principles.

While much of the research cited has originated from academic medical centers, the fundamental data and analytical approaches are applicable to community hospitals, integrated health systems, and insurers of all sizes. Established methodologies for analyzing inpatient palliative care ROI have been disseminated nationwide through programs like the “Palliative Care Leadership Center,” operated by the Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) since 2004. Similarly, data-driven approaches for planning and evaluating CBPC programs are increasingly available.

Utilizing These Principles: Building a Business Plan

These 10 principles provide a framework for developing robust Palliative Care Program Business Plans and advocating for program expansion and sustainability. Here are key applications:

1. Guiding Future Research: Researchers should recognize areas where empirical evidence remains limited, such as the impact of CBPC in non-cancer populations, the proportion of palliative care program budgets covered by clinical revenue, and the detailed financial margins of end-of-life hospitalizations relative to revenue. Research in these areas is crucial. However, access to health system revenue and net margin data, often considered proprietary, can be challenging to obtain. In the FFS environment, understanding the relationship between care costs and revenue is paramount for assessing the sustainability of current practices and evaluating innovations like palliative care.

2. Developing Program-Specific Business Plans: These principles serve as a blueprint for creating tailored business plans. Each principle can be substantiated with institutional data, demonstrating the clinical need for expanded palliative care services, the potential impact of inpatient and/or CBPC, the anticipated or existing funding gap, and the costs associated with end-of-life hospitalizations within specific disease groups. These data points can be synthesized into a compelling business case for administrators. Palliative care leaders must understand these principles to articulate their value proposition effectively and recognize their institution’s position within the evolving healthcare reimbursement landscape. Is the institution deeply entrenched in FFS, or is it actively transitioning to value-based care models? This context will significantly influence the receptiveness to different aspects of the palliative care business case. Securing support for CBPC may be particularly challenging in institutions firmly rooted in FFS models and not actively participating in ACOs or other value-based initiatives.

3. Local Data Validation: Research findings from other institutions, while informative, may not always be perceived as directly relevant to a specific local context. Local data is often essential to build a compelling business case. Published research then serves to validate and support these local findings. However, generating local evidence, particularly for principles like the increased frequency and cost of ED visits and hospitalizations near the end of life, requires sophisticated financial analysis capabilities. Technical assistance resources are available from organizations like CAPC, the California State University Institute for Palliative Care, and the California Coalition for Compassionate Care to support these analyses.

Limitations

Beyond the identified gaps in evidence, the primary limitation of this review is the reliance on findings from predominantly non-experimental studies. Observational research inherently carries the risk of selection bias. Researchers have employed techniques like instrumental variables and propensity score matching to mitigate these biases and create matched comparison groups. A recent study using extensive clinical and demographic data for propensity-based matching demonstrated a significant cost reduction associated with palliative care involvement among hospitalized cancer patients, strengthening the evidence base.

Conclusion

In the U.S. healthcare system, often characterized by business transactions and a hospital-centric, revenue-driven approach, implementing innovations that generate immediate revenue exceeding costs is typically favored. Palliative care presents a unique challenge as specialist teams often cost more than they directly generate in revenue, and their interventions may reduce hospitalizations, a primary revenue source for hospitals. Therefore, a specific business case is essential to justify investment in palliative care.

While the U.S. may represent an extreme case in the application of capitalistic principles to healthcare, the global growth of palliative care highlights its universal clinical and ethical imperative. Some principles, like the clinical need for palliative care, are universally applicable, while others, particularly those related to financial models, are more context-specific, especially within FFS systems.

The business case for inpatient specialist palliative care is well-established, reflected in the rapid growth of programs in over 60% of U.S. hospitals. The business case for community-based specialist palliative care is evolving and is most compelling in healthcare systems that are actively pursuing payer-provider partnerships to deliver more efficient, patient-centered, high-quality care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA016059 to VCU Massey Cancer Center; National Center for Advancing Translational Science grant UL1TR000058 to VCU Center for Clinical and Translational Research; and grants 17686 and 17373 from the California HealthCare Foundation. Funders played no role in the content of this article.

The authors thank Diane Meier, Lynn Spragens, Egidio Del Fabbro, Irene Higginson, and Michael Rabow for their valuable contributions.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.